Nicole Laporte’s excellent book The Men Who Would Be King chronicles the whole sad saga of DreamWorks SKG, a place built on impossible promises about a combination of market and artistic friendliness. Since Spielberg was a third of it, there was the hope that DreamWorks could be a beacon for new and hot artists to study under the most successful director alive. While people like Gore Verbinski, Adam McKay, and Sam Mendes did go to the DreamWorks school of filmmaking, Spielberg mostly kept a safe distance, letting his producers and heads of film development, husband-wife team Walter F. Parkes and Laurie MacDonald, run the show and occasionally run roughshod over the directors (King has Parkes telling Verbinski’s crew before they shot Mouse Hunt that, in so many words, they were a bunch of idiots making a bad movie). And a lot of DreamWorks’ output is the same old chaff from the regular studio system mixed in with lame Oscar plays (they ponyed up $80 million for The Legend of Bagger Vance), and when these titles kept bombing, they didn’t even have the padding of a back catalog that could provide home video and TV profits when theatrical profits weren’t up to snuff. Even when they started getting the blockbusters they needed to stay alive, the damage was done and they had to be sold to Paramount at the end of 2005. This is 2004.

What Came Before

2004 exists in the shadow of what Spielberg called DreamWorks’ “first shitty year.” Looking at the record in 2003, it’s hard to argue with that. Their most unqualified hit was Todd Phillips’ Old School ($87 million, $24 million budget), and even that didn’t pull in the numbers of DreamWorks’ other Phillips sex comedy, Road Trip ($119.8 million, $16 million budget). Gary Ross’s Seabiscuit ($148.3 million, $87 million budget) at least got them back in the Oscar race after winning three Picture Oscars in a row and then sitting out 2002 entirely, though it won nothing and DreamWorks’ share of the profits got eaten up by a three-way split between DreamWorks, Universal, and Spyglass Entertainment. Otherwise, you have a string of unqualified flops, including Sinbad: Legend of the Seven Seas ($80.8 million, $60 million budget), which resulted in a $125 million loss that almost bankrupted the studio. And it wasn’t a matter of DreamWorks chasing creative over commercial success, because these titles rarely trend above mediocrity and some, like The Cat in the Hat ($134 million, $109 million budget), tunnel way below.

The Animation

2004 brought one big thing to DreamWorks, the spinning off of its animation division as a publicly-traded company. The separation of DreamWorks Animation from the main DreamWorks SKG meant that Jeffrey Katzenberg no longer had any pretense of sharing the division with Spielberg or David Geffen and could finally preside over a company like he so desperately wanted to preside over Disney. His perpetual dick-measuring contest with his former employer would reflect awfully on him the next year, when, in an attempt to big-foot Disney on DVD sales, he so greatly exaggerated the number of DVDs sold of Shrek 2 that his shareholders sued. But this year, he did just fine against the Mouse, with Shrek 2 ($919.8 million, $150 million budget) and Shark Tale ($367.3 million, $75 million budget) both crushing Disney’s Home on the Range ($145.5 million, $110 million budget) like a bug. I’ve elected to only cover the live-action, SKG side of DreamWorks partly not to step on Jacob Klemmer’s shoes for his piece on Shrek 2, and also because it’s my article and I’m not rewatching fucking Shark Tale for it.

This Year’s Spielberg

The reign of DreamWorks coincided with the most artistically fruitful period in Spielberg’s career. His run of films from Saving Private Ryan thru Munich see him secure enough in his legacy to really start futzing with his own formula, adding notes of unflinching brutality and ambiguity too great to possibly be resolved by a single movie. One of the problems with this run is that they weren’t very helpful to DreamWorks’ bottom line, since the company was started with the promise that investors could expect Spielberg blockbusters, not Spielberg meditations on death and morality that often underperformed (or, as with his two Tom Cruise movies, did well but had DreamWorks’ share of the profits eaten up by co-financing studios or absurd percentages off each box office dollar by Spielberg and his star). The other problem with this run is that The Terminal ($219.4 million, $60 million budget) comes right in the middle of it.

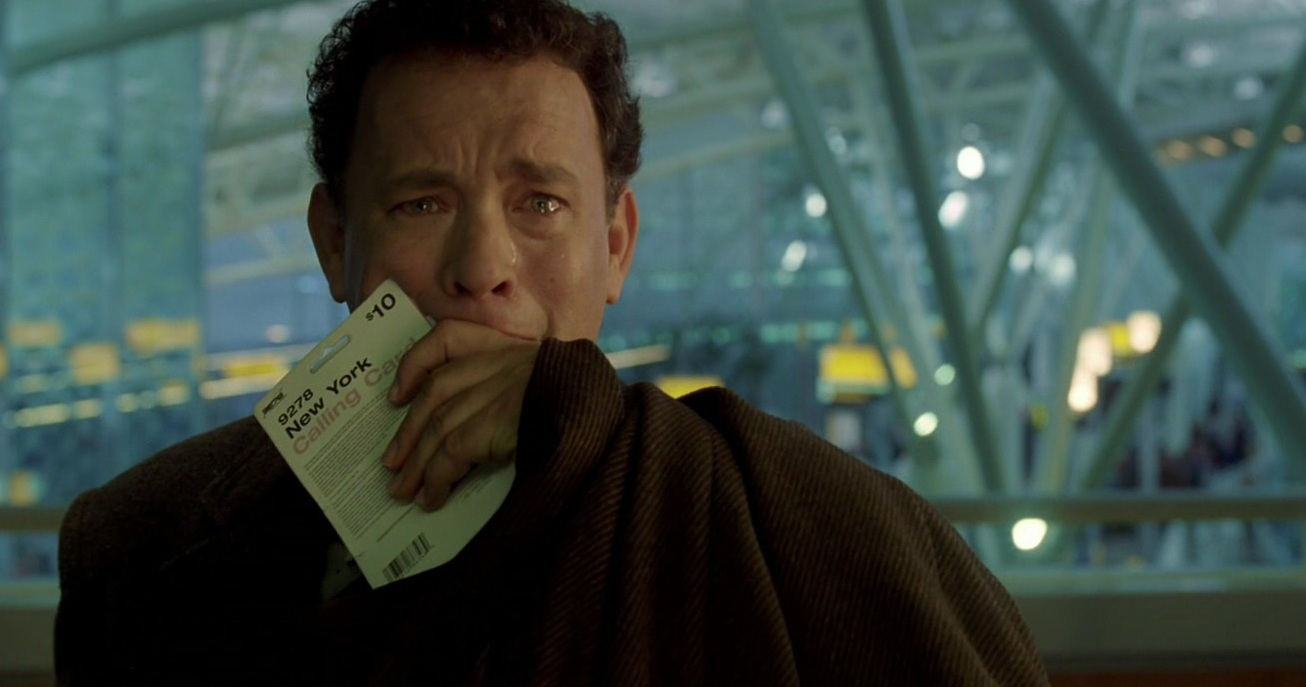

Okay, that’s a little unfair. The Terminal is really not that bad, though it definitely reads as a regression in the middle of a surprisingly tough string of films, its light charm looking disposable next to even the frothy melancholy of Spielberg’s previous film, Catch Me If You Can. Spielberg has said that he made the film because he “wanted to do another movie that could make us laugh and cry and feel good about the world,” a statement that lives down to the most ungenerous readings of Spielberg’s tendency towards sentiment over hard truths. Indeed, the movie orchestrates goofy laughs and tearjerking moments and seems to say that we’re gonna make it through life together, and he’s done all of those things better in previous movies. And yet, there’s something so mid-2000s Spielberg about the fact that this featherweight comedy, mostly driven by Tom Hanks doing an absurd Eastern European accent, still has a geopolitical shadow cast over it, most obviously in the plot device of Hanks’ home country being rocked by Balkans-esque war but also in the unmentioned detail of a post-9/11 movie set entirely in an airport (understandably, an airport set had to be constructed in an airplane hangar because no actual airport would allow filming). A movie about a man trapped by war traps him in the symbol of our own ongoing war, housing him in an open wound that won’t heal.

It’s not a surprise that The Terminal didn’t light the box office on fire. It’s amusing but not much more, its visuals impressive but likely not to the average moviegoer, its subtext interesting but much more “sub” than that of the surrounding Spielbergs. Still, it crossing $200 million is a testament to the strength of the Hanks brand at this time, when only two movies he made from 1992 to 2007 grossed below $100 million (the second of the two, The Ladykillers, came out three months before Terminal). The Spielberg brand is also strong but can falter without stars or an additional hook. The first DreamWorks Spielberg, Amistad ($44.2 million, $36 million budget), is a prime example, offering no box office draws and receiving far more tepid reviews than the acclaim that greeted Schindler’s List, just leaving the vague sense of Importance that gets nobody to the theater even with the Jurassic Park guy directing. The same fate befell DreamWorks’ final Spielberg before its sale, Munich ($131 million, $70 million budget), perhaps the definitive sign that Spielberg couldn’t be counted on for simple matters of profit.

The Masterpiece

2004 may not have brought very much good news to DreamWorks, but it did bring them a masterpiece, and very likely their best movie that’s not directed by Spielberg; Michael Mann’s Collateral ($221 million, $65 million budget). There’s a reason Collateral is beloved by both vulgar auteurists and regular TNT watchers. It’s maybe the only meat-and-potatoes Mann movie, an irresistible premise executed tightly with a minimum of fuss (it could practically be a stage adaptation next to Heat). But of course the fuss is there, just backgrounded and waiting for somebody to discover it. Like pretty much every other Mann movie, Collateral is about the unspeakable loneliness of existence, about how finding a friend in this world is such a long shot that when it happens, it won’t be for long. And it’s about L.A., full of spaces so desolate that it’s a wonder that anybody can retain their humanity when inhabiting them. The magic of early digital means that you see these spaces in a way you never have before on film, Mann filming with such a vast depth of field that the world seems both impossibly big and impossibly empty. You can get none of this and it’s still an A+ potboiler, complete with two of the best movie-star performances of this century. But it’s far more profound than what gets passed off as insight in DreamWorks’ more outwardly prestigey films, which tend towards American Beauty-esque ham-fisted statements delivered with half the art of Mann and receiving twice the acclaim for it. Or at least they usually received more acclaim, as Collateral ended up being DreamWorks’ only major Oscar play this year with its Supporting Actor nomination for Jamie Foxx.

The Really Good

When Will Ferrell and Adam McKay pitched Anchorman: The Legend of Ron Burgundy ($90.6 million, $26 million budget) to Walter Parkes, Parkes told Ferrell in no uncertain terms that he was not a movie star. Following that declaration, Old School was a hit and Elf was a smash, and so DreamWorks stayed in the Will Ferrell business for the time being (though Parkes must’ve still had doubts, since DreamWorks ultimately let Talladega Nights go to Sony). A smart call, considering how much stronger a legacy Anchorman has compared to maybe everything else covered here. Watched now, even long after “Milk was a bad choice” and “LOUD NOISES” have been memed into oblivion, it’s still funny as all hell because you could hardly find a funnier group of people to put in a movie at this time (the dynamics of the actors shifted so much by the time of Anchorman 2, which is still a perfectly good movie, that the same magic could probably never be there). It is easy to see it now as a rough draft for where McKay and Ferrell go with Talladega Nights and Step Brothers, which look better, are smarter critiques, are arguably even funnier (Step Brothers in particular), and don’t have the seams associated with a movie where the original plot was taken out and reshot. But as a pure collection of gags, Anchorman remains untouchable, to the point that it’s difficult to talk about other than to say “it’s funny”. It’s really funny.

The Co-Productions

Much of DreamWorks’ financial misfortune came from it having to share distribution duties with other studios on its biggest hits, often not even getting the more lucrative U.S. distribution rights as part of the agreement. The decision to let Universal handle Jay Roach’s Meet the Parents ($330.4 million, $55 million budget) stateside must’ve really stung by the time Meet the Fockers ($522.7 million, $80 million budget) came around and gave DreamWorks its first live-action franchise without the monopoly on the profits like Shrek. Or maybe DreamWorks had the right idea in the long run, because while Shrek lives on both ironically and sincerely, Meet the Fockers has effectively been memory-holed despite being the seventh highest-grossing film of the year. This is because it sucks, and in a no-fun, mercenary way. Whatever tie to reality that made Meet the Parents even slightly relatable is gone from Fockers, in favor of reprises of Parents‘ wackiest gags that might as well come with built-in applause breaks and a series of new labored gross-out gags involving big boobs, old people having sex, babies saying curse words, circumcision, and toilet fluid. The contrivances needed to get to these shock payoffs only seem worse under Jay Roach’s indifferent lens, Roach leaving behind Austin Powers‘ poppy style for cinematography that’s flat and ugly even by the standards of modern studio comedies. About the only good thing I can say for it is that the actors are all game, particularly newcomers Dustin Hoffman and Barbra Streisand as Ben Stiller’s embarrassing parents, but their commitment only occasionally translates into smiles, let alone laughs (my biggest laugh was Hoffman’s attempt at a touchdown dance). 90 minutes of this would be bad enough, but at 115 minutes it’s practically unbearable. Collateral is only five minutes longer, looks a lot better, and has funnier jokes.

It’s not all bad decisions here. DreamWorks must’ve been more than happy to let Paramount handle at least 50% of Frank Oz’s remake of The Stepford Wives ($103.3 million, $90 million budget). It’s the rare movie where pretty much everyone involved can agree on what went wrong; no clear judgment on what the tone should be, too many cooks in the kitchen. The teaser trailer, one of my favorite pieces of film marketing ever, presents such a radically different tone from the final film that one wonders if it’s just everyday misleading marketing (it’s handled by a different team than the movie itself, including the late, great Harris Savides shooting it) or if there was some point when this was the movie.

Not that a purely comedic take on this material is inherently wrong, especially when the director of Bowfinger and the writer of Addams Family Values are involved. But it starts with pretty much the worse case scenario for this tone, a collection of feeble “battle of the sexes”-themed reality show parodies interrupted when one of the shows’ losing contestants (played by Mike White before he went on all those actual reality shows) tries to murder the executive in charge (Nicole Kidman). Reality TV is about the lowest hanging fruit there is, and to not even be able to reach it (other than one good line from Kidman about giving her attempted murderer a special called Let the Healing Begin) is a sad sight. But things do get better once Kidman and her family move to Stepford (Paul Rudnick was seemingly saving his best material for Stepford, with lines like “let’s celebrate the birth of our lord Jesus Christ with yarn”), at which point Kyle Turner‘s take about it being a camp deconstruction of the male gaze starts to make sense. The grotesquerie of Stepford’s vision of relationships is so strong that, even as it’s played for laughs, it loops back around to the horror of the original, Rudnick’s one-liners providing the only sense of security that gradually gets stripped away. Plus, Rudnick adds some pretty smart additional critiques to the material, most viciously when Roger Bart’s happily flamboyant gay husband gets Stepfordized into Mayor Pete. And it’s all generally helped by how, at this point in her career, Kidman was seemingly unable to not give a powerhouse performance, and she dives headfirst into this material like she does for Birth the same year. Though making Matthew Broderick her husband would be a strange pairing even if Broderick wasn’t giving a bizarrely terrible performance, less like a chauvinist-in-training and more like a victim of hypnosis.

But of course, as everyone says when talking about this, it all comes crashing down at the end. The rumors of the climax being created only in reshoots ring true in light of how perfunctory and dumb it is, walking back every previous attempt at satire and not even having the decency to be funny in the process. And it relies a lot on your belief in Matthew Broderick’s inherent goodness when he hasn’t even been awake, let alone kind, for the entire rest of the movie. But in the haste to turn the movie into something much dumber, one interesting idea gets stumbled upon; Glenn Close as the Stepford den-mother who’s the secret ringleader, the desire to turn back the tide on feminism coming from a Phyllis Schlafly type rather than a man. Granted, this idea would be a lot more interesting if there was more than a scene devoted to it, and if it wasn’t paired to the truly stupid twist of Christopher Walken as Close’s husband being a secret robot. But much like the rest of the film, it’s close to being all the way there, and that’s at least better than its reputation.

If Stepford was ultimately a write-off, DreamWorks was probably pinning a lot more on their other Paramount collaboration, Lemony Snicket’s A Series of Unfortunate Events ($211.5 million, $140ish million budget), namely a franchise that would not come. But in the annals of failed YA franchise-starters, Unfortunate Events is practically Citizen Kane. Enjoying it requires a good tolerance for Jim Carrey at his most schticky, but I think he’s in fine form as Count Olaf and his many disguises, fitting well into the Tim Burton Jr. aesthetic and tone around him. The movie makes a little too much of a show of being “dark” when so much of it is devoted to wacky Carrey hijinks (The Men Who Would Be King suggests that director Brad Silberling was trying for more actual darkness but Parkes fought him on it), but it does build genuine menace, in no small part due to Emmanuel Lubezki’s chiaroscuro lighting (the last gasp of overtly stylized Lubezki before he went exclusively handheld and naturally lit). And compared to The Grinch a few years earlier, Carrey is just one color in a tapestry here, surrounded by a massive supporting cast including bizarre cameos (Dustin Hoffman in a role not nearly notable enough to merit his casting), character actors allowed to get weird (especially Jennifer Coolidge, Luis Guzman, and Jane Adams as Carrey’s minions), an unexpectedly moving Billy Connolly, an unexpectedly goofy Meryl Streep, and tying it all together, the mournful tones of Jude Law (himself at the tail end of a 2004 that would singlehandedly turn the non-Sean Penn American public against him). It may not have provided the windfall that might’ve saved DreamWorks for another year, but it’s solid work all around, and a better Tim Burton movie than anything Tim Burton made after this.

The Michael De Luca Pictures

Introduced in The Men Who Would Be King by way of his motorcycle, Michael De Luca is painted as Hollywood’s version of the Fonz, ready to pound on the quiet jukebox that was DreamWorks in the early 2000s and get it started. His reputation came from his time as the president of New Line Cinema, during which he cemented Jim Carrey’s stardom, gave David Fincher his first hit, and made Paul Thomas Anderson the 90s’ hottest director, all while he was barely into his 30s and usually drunk. He came to DreamWorks in 2001 as president of production, having just been fired from New Line for, among other things, being responsible for Little Nicky. Since Parkes and MacDonald were mostly concerned with middlebrow prestige, there was the hope that De Luca, the man who gave us Austin Powers, could greenlight some more audience-friendly fare. He succeeded at that goal once, by bringing Old School to DreamWorks, and also gave them one somewhat successful Oscar play, House of Sand and Fog ($16.9 million, $16.5 million budget). Otherwise, he largely spearheaded mild flops like Biker Boyz ($23.5 million, $24 million budget) and Head of State ($38.6 million, $35 million budget) and was not taken seriously by either Parkes or MacDonald, leaving the studio after this year. Given that three of De Luca’s four 2004 projects were burned off one after the other at the start of the year, one suspects this was their way of letting the door kick him on the way out.

Both De Luca and DreamWorks’ first 2004 film must’ve seemed like a slam-dunk at the time, Robert Luketic’s follow-up to Legally Blonde. Unfortunately, the project he chose as his follow-up was Win a Date With Tad Hamilton! ($21.3 million, $22 million budget). Featuring a cast so 2004 (Topher Grace, Kate Bosworth, Josh Duhamel, Ginnifer Goodwin, with supporting parts for Sean Hayes, Nathan Lane, and Gary Cole) that watching it for too long might result in Somewhere in Time-esque time travel, it’s mostly just your standard mediocre rom-com, not very funny or memorable. Bosworth and Duhamel, both of whom are now seen as having been too bland to be movie stars, are actually pretty charming together, Bosworth selling her character’s earnestness so well that you suspend disbelief with her casting as a grocery store clerk and Duhamel not falling into the easy pitfalls of overplaying the titular movie star’s vapidity or dickishness. They’re the lucky few well-served by the film. Despite a cast with ringers like Lane, Kathryn Hahn, and Octavia Spencer, the only person to get more than one laugh is Cole, who reacts to his daughter shacking up with a movie star by getting really into Variety lingo. And the retro flair suggested by the Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter?-esque title and the opening with a Tad Hamilton period-piece evaporates instantly in favor of style only slightly above bare competence. But all those faults seem trivial next to the most glaring problem, Topher Grace. Grace has always been better in small doses on film, doing well with his cameos in the first two Ocean’s movies or with recent supporting parts like BlacKkKlansman or Under the Silver Lake. 2004 was the only year studios pushed for Grace as a leading man, and while I haven’t seen In Good Company, his performance here suggests the Grace-as-movie-star experiment was a resounding failure. Grace in Tad Hamilton is a truly hideous performance, a portrait of a man who can only belittle or infantilize (he screams at Bosworth in public to “guard your carnal treasure”) everyone around him, introduced talking too loud in a movie theater and only getting more loathsome from there. This would be fine if he was playing an out-and-out asshole like he is in Traffic, but based on Bosworth’s “oh you!” reactions to his pettiness, we’re clearly supposed to find him charming enough to root for him getting the girl. His nadir is a speech (to Duhamel on the toilet) about Bosworth’s “six different smiles,” in theory powerful enough to merit three separate callbacks in the film but in reality the rantings of either an incel or a future presidential assassin. You keep waiting for Duhamel to do something caddish enough to merit Bosworth running into Grace’s toxic arms at the end, but the most we get is him not loving her quite enough, as opposed to Grace being an asshole because he cares. Yuck.

A month after Tad Hamilton came EuroTrip ($20.8 million, $25 million budget), De Luca’s chance to recreate the magic of Old School and Road Trip with another rowdy sex comedy. It didn’t work at the time, but it’s left more of a lasting legacy than Old School or Road Trip or the majority of DreamWorks’ other projects by virtue of three words: “Scotty Doesn’t Know”. Quite simply, everything about “Scotty Doesn’t Know” is funny; its name, the premise of a guy watching someone brazenly boast about fucking his girlfriend, the fact that it’s Matt Damon “singing”, the fact that Matt Damon is inexplicably bald, “Scotty Doesn’t Know” actually being a great song in addition to a pitch-perfect mall-punk parody, the punchline of Scotty’s dumbass friend shouting “This band rocks!”, the post-punchline of Damon and Scotty’s girlfriend still fucking the morning after. It having such a longer lasting legacy than the movie it appears in (“Scotty Doesn’t Know” even charted on the Hot 100 two years after EuroTrip‘s release) is because it’s an amazing joke/sequence surrounded by mostly good ones. Still, good is a lot better than what else is passing for comedy in this slate. It’s written and directed by three Seinfeld alums, Jeff Schaffer, Alec Berg, and David Mandel, and their sense of comedic energy and timing makes the drawn-out setpieces of Meet the Fockers seem even more excruciating in comparison (it’s also infinitely more stylish than Fockers, understanding the camera can be a way of getting jokes rather than just dully recording them). It’s still a mid-2000s comedy so there’s the expected homophobia (worst of all an extended cameo by Fred Armisen as a handsy Italian man), ableism, and sexism, but it’s mostly charming and silly rather than rancid, admittedly a low bar but one that still isn’t crossed even by the other films on this list. It’s almost nothing but the easiest European stereotypes imaginable, but if you can’t laugh at a particularly well-executed “the Germans like David Hasselhoff” joke, I don’t know what to tell you. And Scotty doesn’t know either.

The last film of De Luca’s DreamWorks tenure coincides with a major mid-2000s event, the first downfall of Ben Affleck. DreamWorks had previously had one of Affleck’s infamous string of 2003 bombs, splitting the bill with Paramount on John Woo’s Paycheck ($117.2 million, $61 million budget), but they were originally going to have two, released on the same weekend. The De Luca-shepherded Surviving Christmas ($15.1 million, $45 million budget) was going to premiere alongside Paycheck at the Christmas 2003 box office, but it was instead punted to October 2004, where it got vicious reviews and was out of theaters so fast it came out on DVD in time for Christmas that year. It’s easy to see the reception as a pile-on at a time when Affleck was the easiest target alive, but this isn’t a Jersey Girl case of an okay movie received like a terrible one. Surviving Christmas is pretty bad, all the more so because one can easily imagine the good version of it. Granted, the good version would likely come from somebody like Yorgos Lanthimos, who would commit to the bizarre dark comedy of its premise; a very rich man (Affleck), so torn up about an impending break-up and spending another Christmas alone, pays a random family $250,000 to pretend to be his family for Christmas, him calling the parents (Catherine O’Hara and James Gandolfini) “mom” and “dad” included. This version of the movie is pitched so broad (especially the gags about Gandolfini and O’Hara’s porn-addicted son) that it doesn’t realize it’s unlocked something truly disturbing and uncanny in its scenes of Affleck, who seems to have fully broken from reality, regressing into a grotesque pantomime of childhood in front of an audience whose only concern is getting their check. A late revelation that Affleck isn’t even basing the act on his own childhood Christmases is inexplicably played for pathos rather than a horrifying confirmation that Affleck is approximating a human being rather than being one. Perhaps the original script, from Josie and the Pussycats writer/directors Deborah Kaplan and Harry Elfont, was more of a satire on the skin-suit qualities of the rich that got sanded down into something a lot dumber. That would make sense considering how uneasily the scenes of Affleck mugging his way through Christmas rituals sit with the later turn into touchy-feely bullshit as he learns about the true meaning of family or whatever. The finished product is 15% as dark as it needs to be, but as executed, that 15% still rattles you.

But let’s not end this with that kind of missed opportunity, and instead end with De Luca’s April 2004 release. His auteur-friendly stance at New Line was enough to bring Barry Levinson (who worked with De Luca on Wag the Dog) back into the DreamWorks fold, even though DreamWorks had so thoroughly buried his Irish toupee salesmen comedy An Everlasting Piece ($75,228, $14 million budget) that the producers filed suit against DreamWorks. Granted, the pretty mediocre Everlasting Piece was never going to be a Full Monty-level sensation, but that box office number is truly pathetic considering what clout Levinson still had in 2000 (even the similarly forgotten Levinson film from the year before, Liberty Heights, crossed $3 million). But his second DreamWorks film, Envy ($14.6 million, $40 million budget), would destroy that clout for good. Shot a good two years before its eventual release, Envy was going to go straight-to-DVD until School of Rock made Jack Black a superstar and even the worst movie could make some money with Black and Ben Stiller as the leads. And it seemed pretty close to the worst movie at the time, its 8% on Rotten Tomatoes sure making it seem like the studio’s pre-Jack Black stardom impulses were correct. Except… it’s a secret masterpiece?

Levinson is a director I resent for wasted opportunity. Avalon is one of my favorite films of all time and he’s made a few other really good ones, but too often his movies just feel half-baked in a way that reflects badly on him, where he clearly has immense talent and chooses to make anonymous programmers instead. But Envy is far from anonymous. From the first shots, a series of Gaspar Noe-esque 180-degree spins around Stiller and Black in their respective homes, this is Levinson at his most stylistically adventurous since Toys, and the style meshes a lot better with the tone than it did in Toys. Levinson’s vision of California is grounded in practical realities (dig the bug-net Stiller and Black’s families have to use when they eat outside) even when the set is a bolder shade of green or a camera movement is more dynamic than you’d expect it to be; this provides the germ of reality that Levinson then turns against you when he reveals that you’ve been inhabiting a cartoon world this whole time. The same goes for the script. It starts from a place of understandable human nature; Tim (Stiller) passes up an opportunity (a spray that dissolves dog poo) proposed by his neighbor Nick (Black) and quietly seethes with rage when Nick becomes a millionaire as a result and Tim gets nothing. But from there things start to get real absurd, probably beginning when Nick’s wife (Amy Poehler) decides to run for state Senate despite knowing so little about it that she calls it “small Congress”. And reality fully breaks down when Christopher Walken enters the picture as “J-Man”, an agent of chaos who wanders into Tim’s life from nowhere and takes it over. The plot comes to resemble the “If You Give a Mouse a Cookie” logic of Uncut Gems, and they share a similar view of capitalism as the force that will drive men so far into madness they can’t be retrieved. And Envy is just about as consistently funny in its contortions as Gems is tense, and with as few concessions made along the way. Surviving Christmas put my teeth on edge waiting for this to inevitably fall into unconvincing mush. It never does. Perhaps Larry David’s producer credit emboldened everyone making this to take “no hugging, no learning” as their mantra, because nothing is learned from a tale this poisonous and we’re all better for it. Of course, its breakneck absurdity and refusal to get sentimental for even a second may have contributed to both DreamWorks and audiences’ antipathy for it. Their loss.

The Conclusion

It’s easy to see why DreamWorks as its own entity was not long for this world after 2004. Not a lot of hits, a few massive bombs, and the weight of every past failure finally becoming too much to bear. But god, what a fascinating group of films to consider together, only one not at least rising to interesting and the rest offering a fascinating glimpse into this year in Hollywood, the icons made (Will Ferrell and Jack Black), continued (Tom Hanks and Jim Carrey), cruelly tossed aside (Ben Affleck and Barry Levinson), and only briefly attempted (Topher Grace, just Topher Grace). I hope that Spielberg, Parkes, MacDonald, and De Luca can now look fondly on the final days of their failed experiment, where they were churning out works far more interesting than the ones that kept the lights on. But if they think that way now, I hope they don’t tell Scotty about it. Because Scotty doesn’t know.

The Ranking

- Collateral

- Envy

- Anchorman: The Legend of Ron Burgundy

- Lemony Snicket’s A Series of Unfortunate Events

- EuroTrip

- The Terminal

- The Stepford Wives

- Win a Date With Tad Hamilton!

- Surviving Christmas

- Meet the Fockers