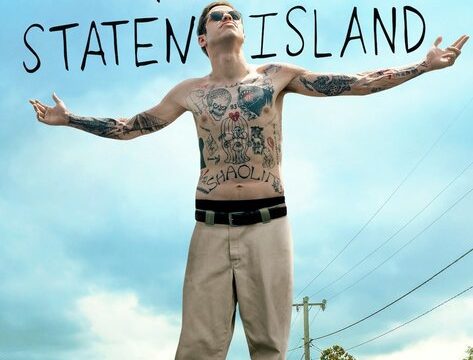

Despite what the title of The King of Staten Island would have you think, Scott Carlin (Pete Davidson) is far from royalty. He’s a 24-year-old stoner still reeling so hard from the death of his firefighter papa who’s going nowhere in life. Carlin’s got a passion for tattoos, a constant detached attitude, and absolutely no plans to move out of his mom’s (Marisa Tomei) house. Any changes in his life, like the departure of his High School graduate sister, Claire (Maude Apatow), or his mom getting a new boyfriend in the form of Ray Bishop (Bill Burr), tend to bring out the most frustrated side of Scott. What’ll it take for him to grow up? Scott may never be a king of Staten Island but can he at least become something resembling an adult?

The King of Staten Island, the newest directorial effort from Judd Apatow, leans heavily on the life of its leading man, Pete Davidson. Though heavily fictionalized, Scott Carlin still makes use of numerous facets of Davidson’s actual life, including an affinity for weed, a Crohn’s disease diagnosis, and losing a firefighter father at a young age. The parts of The King of Staten Island (which was also written by Davidson as well as Apatow and Dave Sirus) that work best tend to be the ones that dig into something that feels deeply personal on the part of Davidson. A scene where Scott goes on a tangent berating what he perceives to be his own shortcomings (like his ADD), for example, lends a deeply wounded motivation for Carlin’s current state.

Everyone may be critical of Scott but no one has more contempt for this guy than himself. That more raw storytelling detail is indicative of how The King of Staten Island is a bit darker than the average man-child comedy. This is also reflected in the more grounded look of the whole production. Apatow and cinematographer Robert Elswit have eschewed the highly-saturated appearance of most American comedies. Instead, they film Staten Island with washed-out colors and in 35mm film. Apatow’s tendency to prioritize improvised comedy over well-blocked scenes means these visual qualities aren’t used to their fullest potential but at least The King of Staten Island looks more like a movie than, say, Daddy’s Home.

Unfortunately, the screenwriting of The King of Staten Island also fails to fully go the distance. Despite The King of Staten Island opting for a more muted character-centric aesthetic, its exploration of Scott Carlin as a person ends up being surface-level. The best parts of Staten Island, like Carlin’s moments of self-loathing, confront the messy and dark parts of Carlin’s reality. Unfortunately, they’re paired up with storytelling decisions that are far more conventional. Such decisions include the idea to structure Staten Island around a variety of individual misadventures Carlin gets into. Briefly, Scott is working at a restaurant, which includes a fight club over tips. Then he’s briefly walking Ray’s kids to school. Then he’s partying with his sister at a college campus.

Carlin goes to many places but few of them take the viewer deeper into who he is. To boot, it’s puzzling how a story all about the long-term consequences of childhood trauma features so many individual escapades that have little impact on the overall plot. Carlin nearly gets arrested for felony robbery and it has no real bearing on the plot! So much of Staten Island feel like disparate shorts or skits stitched together rather than pieces of a cohesive movie. Most troubling of all, these individual sequences don’t offer up nearly enough laughs to offset the erratic storytelling.

Meanwhile, the best part of Staten Island is the final forty minutes where Scott actually sticks around at a local firehouse that Ray works at. Here, both Staten Island and its protagonist actually stick around in a plotline long enough for the viewer to get invested. Plus, Steve Buscemi is around in this stretch of the story as a veteran firefighter and it’s always good to see Buscemi! The rest of the supporting cast mostly gets undercut by Staten Island’s refusal to stick with one storyline for too long, but they’re delivering mostly solid work.

These supporting players include Bel Powley in the kind of underwritten love interest role that’s practically requisite for the man-child comedy. Powley is fun in the part, even if seeing the performer behind the outstanding lead performance of The Diary of a Teenage Girl playing a disposable love interest role feels like an incredible waste of talent. In the lead role of Staten Island, Pete Davidson does really good work, particularly in making his character feel like a real person. Davidson’s going the extra mile to instill both humanity and a darker edge to Scott Carlins to ensure he’s more than just an extension of his Saturday Night Live persona.

His handling of the most deeply personal material in The King of Staten Island is what stands out the most in this comedy. The King of Staten Island suffers the episodic and overlong tendencies that plague other Apatow movies. However, through Davidson’s willingness to go to darker places, it does a find unique edge, albeit one buried beneath way too many unsatisfying storytelling detours.