The most difficult type of miscasting to pinpoint is that which centers around intangible qualities. Something that’s not physical, that’s not about past work, that’s not even really about the performance, but something far more ineffable.

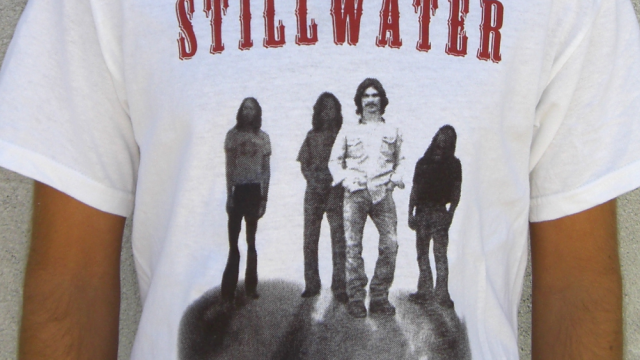

Cameron Crowe’s autobiographical 2000 film Almost Famous tells the story of a 15-year-old writing prodigy William (Patrick Fugit) who is hired by Rolling Stone magazine in 1973, at the height of its power, to follow around an up-and-coming rock band called Stillwater. The young journalist, a Crowe surrogate, travels with the band, gets to know the musicians, and their groupies — excuse me, “Band Aids” — and hopes to snag the white whale itself: an interview with Stillwater’s guitar player, a cool, charismatic rock god named Russell Hammond, the embodiment of the post-Hendrix “guitarist with mystique.” Hammond is unwilling to grant William an interview, and his ultra-hip persona and fame is growing so much that he is beginning to eclipse the other members of the band, causing a rift between Hammond and his longtime friend, lead singer Jeff (Jason Lee). Russell Hammond is also the apple of the eye of Penny Lane (Kate Hudson), an effervescent young “Band-Aid” who is fixated on him. Everyone wants Russell. In short, Russell Hammond is the epitome of the ’70s-era rock star.

And he’s played by Billy Crudup.

Don’t get me wrong, Crudup is a fine actor. But he is no rock star. He lacks the sheer charisma needed to play the part, the magnetism that would cause everyone in the audience to turn to him whenever he’s in the frame. In fact, Crudup is the Guy You Get When You Need Someone Who Is Boring But Talented. He has a very sedate style, and a very normative feel to him. He played Tim Geithner, for Pete’s sake! His most representative roles might be in Big Fish, where his job is to play the intentionally boring, blandly normal son of the exciting and charming Albert Finney/Ewan McGregor, and in the 2009 film version of Watchmen, where he plays a irradiated post-human who has lost all sense of time, cause, and effect, and has become an emotionless, choiceless husk.

(A similar example, in a very weak film, is the casting of Kristen Stewart in Snow White & The Huntsman. The dark-haired, pale skinned Stewart is a suitable physical match to play the character of Snow White, but possesses the entirely wrong energy and appeal for the part in that badly-miscalculated film. In films like Into the Wild and Adventureland, Stewart has a low-key, quietly beguiling fascination to her, but that energy is exactly the opposite for the character as written. One character, describing Stewart’s character in the film, actually says the words “She is life itself,” but Stewart’s near catatonic restraint hardly calls to mind the glory of creation, nor does “Sweet Mystery Of Life At Last I’ve Found You,” seem to emanate when she enters a scene.)

It’s not that Crudup doesn’t look the part — like all the members of “Stillwater,” he is a perfect physical facsimile of a mediocre early ’70s rocker, all shaggy hair and droopy mustache — and it’s not that he brings too much baggage from his other roles — frankly, he’s not famous or particularly distinctive enough to do that. No, it’s something else, something intangible yet utterly perceptible. Crudup performs the part credibly, he never feels like he’s acting, but he doesn’t summon up the needed allure that the character of Russell Hammond needed. It’s a little tricky to think of who else could have capably played the part with the appropriate level of magnetism — McConaughey was still well into his “boring cardboard cut-out” phase, but Sam Rockwell might have provided some off-kilter energy; maybe Crudup could have swapped places with Jason Lee, who is less of a typical Hollywood leading man, but possesses more of a natural humor and charisma. Still, Almost Famous, a fine and charming film, is not sunk by Crudup playing Hammond, he’s too good of an actor and gives a strong enough performance to keep himself reasonably afloat, but the mental gap in the audience mind between what Hammond is meant to represent, and what the presence of Crudup seems to imply, must keep the film from fully landing on the intended level. In other words, you can miscast one of the central roles of your story, and still come out on the other side smelling good. To miscast is, perhaps, not always the end of the world.

So what is miscasting, really? Does it just mean screwing up in the casting process? If you’re doing King Lear and you turn away all the capable actors in favor of talentless hacks, is that really miscasting, or is it just bad casting? Well, of course, miscasting is part of the casting process, which many directors will tell you is the most important part of putting together a good production. We tend to have it in our minds that that means casting “the perfect fit” for a part. But at the risk of stretching the metaphor to the breaking point, perhaps there is an imperfect fit that makes the shirt better. According to Mark Harris’ wonderful book “Pictures at a Revolution,” when Dustin Hoffman was approached by director Mike Nichols to play Benjamin Braddock in The Graduate, Hoffman thought Nichols was crazy, believing that Braddock must have been a six-foot-tall WASP and not the small Jewish character actor Hoffman was at the time. Nichols assured Hoffman that it was okay, that Benjamin must have had “some twisted dark pirate uncle,” somewhere in his bloodline, and that the whole point (although probably unknown to original author Charles Webb) of the movie was “Who is the Jew among the Goyim?” As recounted by Peter Bogdanovich, the director Jean Renoir, when discussing his film The Rules of the Game, once said that you must always cast against type, presumably in order to prevent the character from sliding into cliche and stereotyping.

In the end, maybe casting isn’t just a question of slotting the right actor into the right part, but is something more intangible, hard to touch, to catch, something that may not exist by the rules of man; a science closer to alchemy than chemistry.