Part one here: https://www.the-solute.com/the-good-the-bad-and-the-miscast-part-i-the-physics-of-miscasting/

Miscasting, type two: The Celebrity Problem

It is a truth universally acknowledged that movie stars, well, they tend to be pretty famous. And sometimes that’s a problem. Star power and celebrity can often bring a great deal of meaning to a role, enhancing it, expanding on it — when Sean Connery moved on to the Elder Statesman era of his career, all he had to do was appear on screen for a second and you knew that he was capable of being a complete ass-kicker, despite being well into his old age, because he brought with him all the nostalgia of introducing the world to James Bond. When Vivien Leigh starred as Blanche DuBois in A Streetcar Named Desire, the ghost of Scarlett O’Hara howled in the bones of her face, reminding her and her co-stars of the majesty and romance of the long-since blown away Old South. Even offscreen celebrity can bleed over into the frame. When Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman, or Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor, played out marital strife in Eyes Wide Shut or Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf, it had an added edge of poignancy that the audience could feel because they knew that the couples were married for real. In cases like these, the fictional character blends perfectly with the history and persona of the performer embodying the character.

This does not always work. If the goal of dramatization is, in most cases, to develop a sense of verisimilitude — not to be confused with realism — then celebrity is a double-edged sword. For while it can enhance the impact of a character, or give greater definition to an otherwise flat character, it can also supply an unneeded distraction or an unwanted subtext to a film that didn’t need it.

The most evident example of this in recent memory was the miscasting of Brad Pitt as the character “Bass” in 12 Years a Slave. Pitt, although he’s one of the biggest Hollywood stars of the past two decades, has never been shy about playing smaller roles. He’s taken on supporting parts in ensemble films like the Coen Brothers espionage farce Burn After Reading, or the Ridley Scott existential noir The Counselor. Even some of the more famous roles he’s had over the years do not really qualify as leading roles: everyone loved him in Ocean’s 11, but he’s George Clooney’s sidekick; while his face may have been plastered all over the poster to Inglourious Basterds, he’s got just as much screentime (if not less) than Christoph Waltz and Melanie Laurent. In these roles, Pitt ranges from good to great, and the films are boosted by his appearance, from his sheer movie star charisma in the Ocean’s flicks, to his eccentric performance as a grotesque hillbilly cartoon in Basterds, to the SPOILERS FOR BURN AFTER READING shocking and shockingly hilarious death of his character in Burn After Reading SPOILERS ENDED.

No doubt Pitt’s presence helped many of these films get funded, made, marketed, and released. But his willingness to lend his famous face to potentially-overlooked movies led to near-disasterous results in 12 Years a Slave, and his brief appearance in that film is by far the biggest and most obvious creative error made by director Steve McQueen. In the film, Pitt plays Samuel Bass, a Canadian carpenter hired to work on a plantation run by the sadistic Edwin Epps (Michael Fassbender). The film’s central character, Solomon Northup, a free man of color who was kidnapped years earlier and forced into slavery, overhears Bass arguing with slaveowner Epps. Bass, out of place in Louisiana, expresses egalitarian attitudes towards race, confronting Epps on his racism, denouncing slavery and immoral and unnatural, and stating that he believes no black person to be inferior to him or any other white man. It is this conversation that convinces Northup — who has long since resigned himself to his life in chains, especially after being betrayed by a white cotton picker named Armsby who agreed to help him escape — that he can trust Bass, and confide in him with the details of his plight. When Northup explains his story to Bass, the Canadian agrees to deliver a letter to Solomon’s friends in the free state of New York. It is this twist of fate and act of human decency that allows for Northup to free himself from slavery and return home to his family after twelve years of bondage.

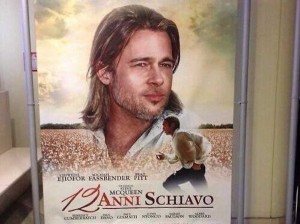

On paper this is a very intriguing turn of events, but it also presents potential problems in the hands of the storyteller. What happens in the film is taken directly from the real Solomon Northup’s memoir of the same name, and Samuel Bass really was a progressive, fair-minded, and compassionate man who was willing to endanger himself to help free another man. It really did happen. But there’s a potential problem there — you don’t want Bass to come off as a heroic white savior riding in on a horse to save the poor black man. There are ways to ensure that, as a director. One of those ways, however, is not casting the biggest leading man in Hollywood in a two-scene cameo. Pitt, in 12 Years a Slave is both a distraction and a bad loose end. His screentime is too brief for the audience to get used to his famous face as that of a Canadian carpenter, and the fact that he’s the biggest star in the film and the film’s producer, and that he gets the most sympathetic white role, all comes together to dilute the strength of the film. The miscasting of Pitt risks turning the film into what this unintentionally hilarious Italian poster promised: tiny Chiwetel Ejiofor running to the warm, soft embrace of Brad-Jesus’ beard.

Pitt in 12 Years a Slave was chosen here as a point of reference for its particularly egregious nature, its prominence, and the fact that it is in recent memory, but there have been many other instances of similar “celebrity” miscasting in other films. Take, for instance, the odd duck that was Lee Daniel’s The Butler. At the center of the film was a trio of strong performances and character struggles embodied by Forest Whitaker, David Oyelowo, and Oprah Winfrey. And than, on the sidelines, are a bizarre string of brief appearances by recognizable stars. The late Robin Williams plays Dwight Eisenhower. John Cusack appears as Nixon. Liev Schreiber plays LBJ, James Marsden is JFK, and Alan Rickman is Ronald Reagan. These cameos were heavily mocked and much derided. But the truth is that, believe it or not, they’re not bad performances. Really! Robin Williams is subdued and grandfatherly as Eisenhower. Alan Rickman was good enough that I wanted to see a whole movie where he played Reagan. James Marsden made a good, and affecting JFK with just a handful of scenes. Cusack was a pretty over-the-top, but Nixon was kind of an over-the-top guy. Only Schreiber (with maybe two minutes of screentime) I would actually describe as not delivering a good performance — he’s too cartoonish, even for LBJ. But the problem is that these cameos should not be happening. At least, not in the way that they are. A cultural icon like Robin Williams cannot just show up for two scenes and convince you that he’s President Eisenhower! That’s not a knock on Williams, it’s just to say that he’s so recognizable and so iconic that the audience has no time to get adjusted to him as Eisenhower before he’s offscreen. The same with Rickman as Reagan. As mentioned before, I would want to see an entire film where Rickman plays Dutch, but when he’s just in a few scenes, we spend the entirety of the time trying to get used to him in that role, and thus it proves to be a distraction, and a distraction from a good performance, at that.

Fame is a potent thing. It can get a film made. It can turn a good film into a great one. It can also risk wrecking the film. Like all aspects of casting and miscasting, it has to be used well, or else you end up unintentionally seeming like Charlton Heston’s appearance as the Helpful Old Man in Wayne’s World 2.

Be sure to check out part 3 on Friday