As the American football season opens, it is worth thinking about how watching the games on television can often feel like watching comic-book superhero movies: as with the frequent stoppages in play to sell corporate products, these movies self-consciously and continuously promote the Hollywood brand–not to mention, of course, that many of these movies flaunt their corporate tie-ins. It is even possible, albeit from a rather cynical frame of mind, to compare the typical game plan of a football team with the strategy of a superhero movie: a key to victory is to wear down the defense of the opposing team, the resistance of the viewer.

There is, however, a vastly different, although similarly named, sport that attracts the attention of a greater number of viewers in the world: international football—better known, in the States, as soccer. In particular, a crucial difference is that international football matches have no commercial breaks during play (only at halftime); corporate logos are featured on the players’ jerseys and all over the stadiums. Thus the games move much faster with a greater sense of flow.

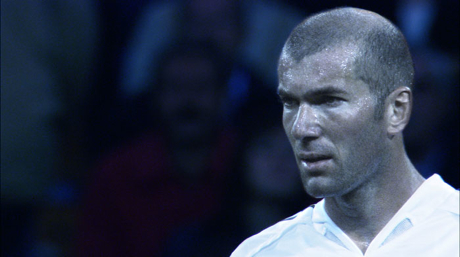

The premise of Zidane: A 21st Century Portrait (2006) is simple, yet fascinating. Take a superstar football player, Zinedine Zidane—the winner of World Cup, European Championship and European Cup titles, his 2001 transfer from Juventus to Real Madrid costing, at the time, a record £47m—and focus only on him for the duration of a single match (around 90 minutes), using multiple camera angles and manipulated sound. You can watch the film here.

The film’s directors, Douglas Gordon and Philippe Parreno, keep the actual 2005 match, Real Madrid vs. Villareal, in the background. Playing for Real Madrid, Zidane takes on the superhero power of being everywhere at once. He is a shape-shifter, a pixelated image, a blur of motion that transforms into flesh and blood in an instant. Zidane also changes size, appearing as miniature in overhead shots of the game, becoming a giant when he is the sole figure in the center of the frame.

The film’s directors, Douglas Gordon and Philippe Parreno, keep the actual 2005 match, Real Madrid vs. Villareal, in the background. Playing for Real Madrid, Zidane takes on the superhero power of being everywhere at once. He is a shape-shifter, a pixelated image, a blur of motion that transforms into flesh and blood in an instant. Zidane also changes size, appearing as miniature in overhead shots of the game, becoming a giant when he is the sole figure in the center of the frame.

Furthermore, Zidane seems nearly indestructible. When a hard foul, early on, sends him crashing to the ground, he gets up as quickly as he went down. His intensity and focus is indicative of a world-class athlete in the zone, in his own world.

Unfolding in real time, the film blends the reality of the match into a fantasy world of heightened and altered perceptions. The constant barrage of crowd noise is filtered out for much of the film. The sonic landscape shifts from the voice of a television announcer to Zidane’s breathing and the sounds of cleats on turf, the soft thump of contacting the ball. At times we hear Zidane briefly shouting to other players. Also foregrounded in the film, a minor-key instrumental score consisting of guitar, keyboards, drums, and bursts of feedback, by the Scottish space-rock band Mogwai (that wouldn’t appear out of place on an early Pink Floyd record), helps to build the hypnotic atmosphere.

Considered together, the music, Zidane’s relentless pacing up and down the field (he never stops moving), and the diverting of our attention from the logistics of the game open up existential questions: what does this performance mean? Is Zidane imprisoned or freed by the space of the playing field, the clock, the crowd watching his every move? Zidane’s own thoughts, that appear in text at the bottom of the screen, give added weight to such questions: “Sometimes when you arrive in the stadium, you feel that everything has already been decided. The script has already been written.”

Considered together, the music, Zidane’s relentless pacing up and down the field (he never stops moving), and the diverting of our attention from the logistics of the game open up existential questions: what does this performance mean? Is Zidane imprisoned or freed by the space of the playing field, the clock, the crowd watching his every move? Zidane’s own thoughts, that appear in text at the bottom of the screen, give added weight to such questions: “Sometimes when you arrive in the stadium, you feel that everything has already been decided. The script has already been written.”

The film does depict the key moments of the match. In the first half, a penalty kick (for any foul committed in the goal area that would prevent a probable chance to score) is awarded to Villareal. A player lines up the ball, facing only the Real Madrid goalkeeper. The goalkeeper can’t move until the ball is kicked, putting him at a considerable disadvantage. Predictably, the ball goes into the back of the net—although we don’t see it happen, the reactions of the players tell us that a goal has been scored.

Zidane wastes little time in berating the referee for the call. Since low-scoring games are the rule in football, being down even by one goal is a serious matter. In the second half, Zidane rallies his team by assisting on the tying goal. His team then scores the go-ahead goal.

We don’t need to hear the crowd to feel the excitement when the goals are scored. Not only is there the growing expectations of a happy ending; there is the pleasure of watching Zidane give a memorable performance. And we appreciate all of the technological wizardry for our being able to experience football in a way that nobody in the stadium could.

But the ending is significantly different than what we might expect. While the match is winding down, a scuffle suddenly breaks out at one end of the field. Zidane jumps into the fray and is sent off. Unlike in American football, an ejected player is not replaced, forcing the team to play shorthanded for the rest of the game. While Zidane’s leaving the match in no way affects the outcome, it can’t help but tarnish his performance.

Thus the film ends on a disconcerting note. For whatever reason (the film gives no definitive answer), Zidane loses his cool, and pays the price. Our superhero is revealed to have all too human flaws. The game seems not just a dramatic event, but a tragedy at that. There is a resounding echo of Shakespeare’s Coriolanus.

Like with all art, we seek access to a bigger picture. In Zidane’s case, a far greater tragedy was to come a year later. During the closing 11 minutes of the 2006 World Cup final, Zidane, playing his last ever match for France, was again ejected, this time with the outcome of the game in the balance (the score was tied). Insulted by a defender on the Italian team, Zidane head-butted him in the breast-bone. Once more, Zidane’s outburst overshadowed his heroic efforts, having been for the entire match the dominant player on the field. His team lost the penalty kick tiebreaker, and therefore the final.

Like with all art, we seek access to a bigger picture. In Zidane’s case, a far greater tragedy was to come a year later. During the closing 11 minutes of the 2006 World Cup final, Zidane, playing his last ever match for France, was again ejected, this time with the outcome of the game in the balance (the score was tied). Insulted by a defender on the Italian team, Zidane head-butted him in the breast-bone. Once more, Zidane’s outburst overshadowed his heroic efforts, having been for the entire match the dominant player on the field. His team lost the penalty kick tiebreaker, and therefore the final.

The lesson for Hollywood: it would be hard indeed to imagine such a gripping story. In their haste to assemble gigantic fictional universes, the major studios overlook the power of the real to create powerful art. For superhero movies to be memorable, the human characters, even when they are seen as beyond human, like Zidane, must turn out to be flesh and blood.

And, whether they are human, superheroes must feel the weight of history, no matter how recent or transitory, pressing down on them. Their actions should be measured against the historical arc of genres such as romance (discussed in Part 4 of this series) and tragedy.

No matter how big superhero movies become, superheroes need to have a profound reason for taking center stage. There is growing frustration that characters have nothing to do, really, having been reduced to plot functions. When after all, what they do, or don’t do, has all the meaning in the world.

To put all of this in sharper perspective, there could be an alternate outcome in which Zidane doesn’t act irrationally at the end of the World Cup final. It has to be a possibility, otherwise it wouldn’t have been as heartbreaking when Zidane is sent off. In making superhero movies, Hollywood has to be committed to raising the emotional stakes just as high, if not higher.