As is a Hollywood truism, the selling point of comic-book superhero movies is that they offer a visceral thrill. But the major studios appear fixated on the amusement park model, where people tend not to stop and admire the design of the roller coaster after the ride is over. Conversely, films such as the James Bond franchise have long hooked viewers by their design, boasting catchy theme songs—a personal favorite is from You Only Live Twice (1967)—and shiny gadgets.

Of course, the cracks still show in Bond films: evil megalomaniacs who always let Bond somehow escape and interchangeable female characters, often simply referred to as Bond girls. Even worse, there is a grim authoritarianism that hangs over the films, most clearly seen in the films starring Sean Connery, who tended to play the character with at least some realistic traits of a dedicated (possibly psychotic) British Cold War-era secret agent.

What if an Italian film decided to have more fun with the idea of the super spy (without resorting to outright parody), while retaining many of the strengths of the Bond franchise? In 1968, Danger: Diabolik did just that. A pretty good dubbed version can be watched here.

Danger: Diabolik turned the superhero/villain opposition on its head by having the superhero work against the government, rather than for it. The film featured the more trippy aspects of the late 60s, such as fuzzed-out guitars, underground clubs where people turned on, and circular walkways and stairwells (accentuated by wide-screen effects).

And, yes, it wasn’t afraid to camp it up (with largely B-grade special effects). But, I would argue, it stands distinctly apart from the so-called martini films that are watched simply for a nostalgic (whether imagined) buzz, or films that are hate-watched for their cheesiness. This is because the film makes smart choices about when and how it departs from reality.

Take, for instance, the first scene. The film is openly cynical about bureaucracy; not just due to the widespread social unrest of the late 60s, but the instability of the nameless government that would strike anyone in Italy, such as the film’s director, Mario Bava, as certainly believable. Diabolik easily heists a government shipment of money, then escapes a pursuing helicopter by switching getaway cars in a tunnel.

He is assisted by the stunningly attractive Eva Kant. Having arrived at their undersea hideout, they passionately make out. The theme song, composed by Ennio Morricone (best known for his scores for Sergio Leone’s spaghetti westerns), starts: languid female vocals are layered over a catchy, bending guitar riff that, fuzzed out, jumps from the speaker. An apt comparison would be the theme to You Only Live Twice, but the song for the Bond film follows a traditional verse/chorus structure, while this song is more circular and floating—and, as you might guess, more sensual, promising pleasure.

He is assisted by the stunningly attractive Eva Kant. Having arrived at their undersea hideout, they passionately make out. The theme song, composed by Ennio Morricone (best known for his scores for Sergio Leone’s spaghetti westerns), starts: languid female vocals are layered over a catchy, bending guitar riff that, fuzzed out, jumps from the speaker. An apt comparison would be the theme to You Only Live Twice, but the song for the Bond film follows a traditional verse/chorus structure, while this song is more circular and floating—and, as you might guess, more sensual, promising pleasure.

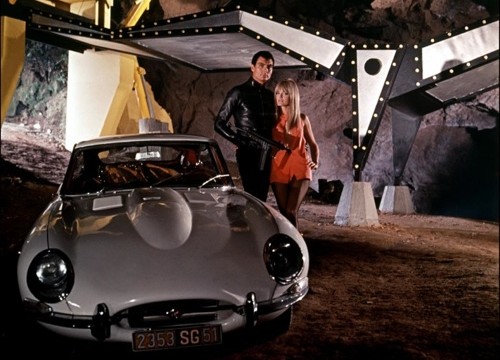

All the while, the camera tours through the hideout, which looks incredible, as if no money was spared (our superhero, after all, being independently wealthy) to make it look as comfortable and visually pleasing in design (featuring white circles set against black rectangles) as possible. In Bond films, the villain’s hideout is not shown frequently, because the emphasis is on the super spy, who hangs out in luxury villas—that look realistic, because the purpose is to help viewers fantasize that they are wealthy globetrotting tourists along for the ride. In contrast, Diabolik’s residence is simply too cool to be real, which makes it even more cool.

After the heist, they clean up, taking separate showers. No one can say these two ever rush doing things. The point here is that we get to know better the main characters and where they live, instead of getting only a brief, hastily sketched impression. This is, then, a superhero movie that takes the romantic aspect of the genre quite seriously. It also shows the value of leisure, as opposed to working in a soulless bureaucracy.

After the heist, they clean up, taking separate showers. No one can say these two ever rush doing things. The point here is that we get to know better the main characters and where they live, instead of getting only a brief, hastily sketched impression. This is, then, a superhero movie that takes the romantic aspect of the genre quite seriously. It also shows the value of leisure, as opposed to working in a soulless bureaucracy.

In charge of capturing Diabolik, Inspector Ginko is played by Michel Piccoli, truly a heavyweight actor best known for his heart-wrenching performance in Contempt (1963), directed by Jean Luc Godard. His character is, in many ways, the film’s emotional center—in compelling drama (for instance, Shakespeare), we often identify with the villain, rather than the hero. We get the sense that although the Inspector does not like his job very much, he still tries to do the best he can, but is exasperated at every turn by bureaucratic incompetence and Diabolik’s cunning.

In just one of many miscues, the government decides to work with a notorious mob boss, who controls the club scene (and the trade in hard and soft drugs), in order to track down our superhero. The mob boss is greedy, amoral, and sadistic, even willing to have Eva tortured to lure Diabolik into rescuing her.

This collusion with the mob (another thing, of course, that wouldn’t surprise Italians) makes the government look even worse. When the government puts a price on his head, Diabolik retaliates, for what he claims, in a letter addressed to the Police Chief, is misuse of public funds, by blowing up the tax offices. Because the records have been destroyed, the government is reduced to begging its citizens to pay their taxes. Which no one does, since—borrowing from the philosophy of Thoreau, Gandhi, and MLK—it is morally unprincipled to support a corrupt leadership.

Like Lemmy Caution, in Alphaville, and El Topo, Diabolik is a nonconformist, who is viewed as dangerous by the government because he might give people the wrong idea about the consequences of not submitting to authority. At the same time, the mob boss, who is later fatally shot by Diabolik, reminds us that the film does not endorse all criminal acts; some legal transgressions benefit the interests of those in power. Instead we see crimes committed by our superhero as acts of individual rebellion against a government that the people oppose.

Danger: Diabolik may not have much in the way of a cohesive plot (like so many Bond films), yet does build to a grand finale. Our superhero steals a government gold shipment. The shipment, however, is traced, and the police surprise him and Eva at their hideout. He orders Eva to leave, but not before telling her that she’ll never be alone while he lives. Pinned down by gunfire, he can’t shut off the laser being used to melt down the gold, which overheats. A huge explosion showers Diabolik with molten gold, entombing him. The Inspector arrives and claims it is “barbaric” to display “the body of a fallen enemy” in such a way. His protest is met with the assurance that “it is good propaganda for the Minister.” Eva returns, and the Inspector allows her one last moment alone with Diabolik. He winks at her, signaling that he is still alive. The film ends as we hear his laughter echoing off the undersea walls.

Hollywood could have a field day reversing the moral polarity of the comic-book superhero universe, as Danger: Diabolik does. A similar lesson is to make superheroes attractive for their nonconformity, for knowing which laws to break, and how to do this with style. Sadly, fuzzed-out guitars may not come back any time soon in cinema, but romance—even and especially when it is combined with an attitude of coolness under pressure—never goes out of fashion.