This week marks ten years since the release of Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow, the CGI/live-action hybrid starring Jude Law as a pulp-era pilot and adventurer. I saw it in the theater, but apparently I was in the minority: although Sky Captain topped the box office in its opening weekend (according to Box Office Mojo), it ultimately failed to recoup its reported $70 million budget. Reviews were mixed: Roger Ebert praised its “heedless energy and joy,” but Peter Travers dismissed it, saying, “It’s a gimmick, not a movie.”

However disappointing it may have been from a box office standpoint, however, Sky Captain has continued to find fans who respond to its stylish recreation of the newsreels, comics, and serials of the 1930s and ‘40s. It turns out that people who like it really like it, and any discussion of it that I’ve encountered online usually includes at least one variation of the sentiment, “I thought I was the only one who loved this movie!”

Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow is a cult movie in the truest sense, and (along with John Carter, another underperforming throwback fantasy) a treat for aficionados of the “real stuff.” Every frame reveals an underlying affection for its source material, and the film itself was a labor of love for writer/director Kerry Conran and his brother Kevin, who designed the production and costumes. It was their six-minute short film, assembled on home computers using off-the-shelf animation software, that caught the attention of producers Marsha Oglesby and Jon Avnet of Paramount. (The original film was presented as the first chapter of a serial; it was expanded and remade as the opening act of the finished feature.)

Avnet’s connections and Paramount’s budget made it possible to cast stars Jude Law, who has the good looks and icy charm to play the title character as an old-school matinee idol; Gwyneth Paltrow as Polly Perkins, a headstrong reporter in the mold of Lois Lane; and Angelina Jolie as Franky Cook, an old flame who helps the heroes at a key moment. (A common complaint is that Jolie, prominently featured in the marketing, is hardly in the movie, but I can’t blame the producers for emphasizing the presence of one of the biggest stars in the world in their film. For me, she has just the right amount of screen time: her appearance makes an impression without overwhelming the central pairing of Law and Paltrow.)

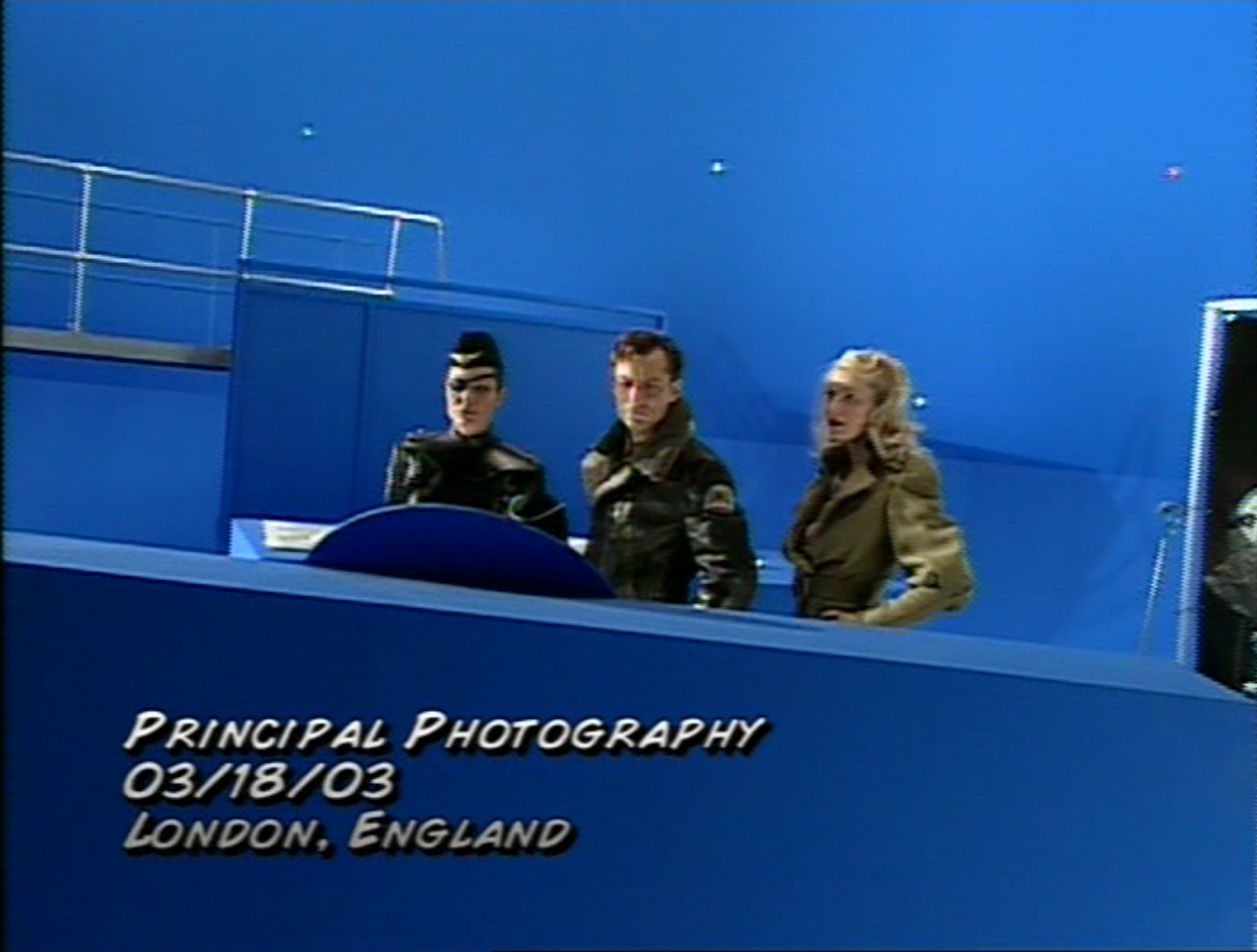

Sky Captain is largely remembered as the first “CGI backlot” film: although the Star Wars prequels included many computer-generated backgrounds and effects, no non-animated film had been as completely digitized as Sky Captain in 2004. The actors were confined to a sound stage in front of a blue screen for the entire filming, with everything but their costumes and the props they handled added in post-production. Instead of the unnatural clarity and brightness sometimes associated with CGI, Conran and his animators developed a shadowy, expressionistic aesthetic that recreated the soft focus of black-and-white movies and the delicate shades of early Technicolor, aping the look of a Republic serial but filling the screen with vehicles and robots the Lydecker brothers could only dream of filming. Atmospheric sound design and committed performances go a long way toward giving the computer-generated objects weight and solidity. Since then, computer graphics have advanced in sophistication and other films have used the all-CGI approach to extremely stylish ends, but Sky Captain has aged well: it was meant to look old-fashioned from the beginning.

Like Lucas and Tarantino, Conran cultivates a magpie aesthetic that makes room for all his favorite things: in this case that includes the aforementioned serials and newsreels (newspaper headlines spin out toward the viewer and appear as larger-than-life backgrounds; stylized radio waves emerge from broadcasting towers, covering the globe in concentric circles), as well as the futuristic designs that graced the covers of magazines like Amazing Stories and Popular Science. There is a classicism in Conran’s use of iconic images: as an example, the giant robots who attack New York City, mechanical agents of the mysterious Doctor Totenkopf, recall all those who came before, from the Fleischer Studios Superman episode “The Mechanical Monsters” to The Iron Giant.

The story and characters are likewise drawn from pulp archetypes: Sky Captain is a pilot and mercenary whose secret base, private air force, and team of specialists bring to mind the Blackhawks and Doc Savage, among others. Franky Cook resembles a female Nick Fury, down to the eyepatch and flying aircraft carrier. Originality isn’t a primary concern, although the crazy quilt of references and Easter eggs are pulled together with a great deal of grace and personality. That might not have been enough for general audiences who felt like they had seen it before, but the attention to detail is catnip for those on the film’s wavelength.

That does bring me to my sole criticism of the film, although it’s a good problem to have: it’s exhausting, so full of wonders and cool ideas that it can be numbing. Around the time Cook’s squadron of submersible fighter jets slip under the water to take on an army of giant robot crabs, I start to think of the downside of getting everything you wish for. Unlike serials, which were generally watched in weekly installments, or a comic book or story, which could be read at the reader’s own pace, Sky Captain is unrelenting, with the kind of “this happens, and then this happens, and then this happens” plotting I associate with Edgar Rice Burroughs at his most hyperactive. Still, I would rather have that than the too-frequent alternative: not once is the action interrupted for a long-winded speech to the League of Nations.

(Note: from this point on there are SPOILERS for the ending of Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow.)

Ultimately, Doctor Totenkopf turns out to be something quite unexpected: when Sky Captain and his team arrive at Totenkopf’s secret island headquarters, they discover that the mad scientist has been dead for years. His mechanical servants have been carrying out his orders, programmed to complete their task—a task which will incidentally destroy the earth if allowed to succeed. In a few key scenes, hologram projections of a younger Totenkopf appear: first delivering a warning to intruders, later a pre-programmed valedictory speech as his life’s work nears completion. Totenkopf is played in these projections by Sir Laurence Olivier; his scenes are adapted from existing footage, since the actor had been dead since 1989.

I have mixed feelings about that. At least since 1997, when scenes of the late Fred Astaire from Easter Parade and Royal Wedding were digitally modified to show him dancing with a Dirt Devil vacuum cleaner for a series of commercials, it’s been possible to change the context of an actor’s appearance using the same technology that can put Jude Law in an airplane when he’s actually on a sound stage. The Dirt Devil ads, although licensed by Astaire’s widow, were controversial, and raised questions that have still not been settled: who owns an actor’s image, and are there limits to the uses to which it can be put? More importantly, does legal ownership give someone the right to tinker with a classic film? The battle lines are not always clearly drawn, as colorizing enthusiast Ted Turner became the patron of a classic movie channel that is widely respected for its thoughtful presentation of all kinds of film, and George Lucas, who spoke out against colorization in the 1980s, has defended his right to modify his own Star Wars movies because they were “his” films.

I’m less offended by the use of Olivier’s image in Sky Captain than by Astaire in the Dirt Devil ads—or by the use of Audrey Hepburn’s image in Dove chocolate commercials just this year—of course: however pulpy it may be, Sky Captain is a work of art, not a commercial. But it is worth noting how far we have come, that such things are not only possible but routine. Connie Willis, in her 1995 novel Remake, depicted a future Hollywood dominated by digital effects, in which hardly any new movies were made, but instead older ones were remade by computer with digital copies of past stars (Back to the Future remade with River Phoenix, for example). We’re not quite to that point, but it hardly seems like science fiction any more, does it?

Perhaps it’s a stretch, but I like to think that “casting” Olivier as Totenkopf was more than a touch of the hat to old Hollywood. It makes perfect sense to cast a digitally resurrected ghost as a man whose programs continue running without him, long after he has passed away.