This Week You Will Turn the Page On:

- Book adaptation

- Advice letters

- Historical fiction

- Literary data

- International prizes

Thanks to scb0212 and Miller for contributing this week. Send articles throughout the next week to ploughmanplods at gmail, post articles from the past week below for discussion, and Have a Happy Friday!

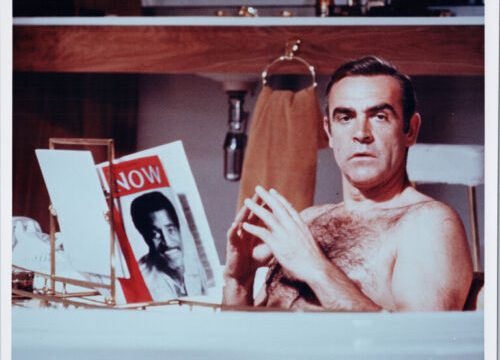

At Fatherly, Ryan Britt reminds how 60 years ago the revolutionary casting of Sean Connery as James Bond was far from a sure thing:

And when you watch what happens in Dr. No, the grittiness of Connery’s first James Bond performance is striking. Yes, he’s introduced in a swank casino, smoking a cigarette and looking cool, but by the end, as he’s trying to escape Dr. No’s lair, Connery looks like Bruce Willis in Die Hard. Through sheer strength of performance, Connery’s James Bond is both an everyman, and unlike anyone you’ve ever met. In Fleming’s novels, the character of Bond is arguably somewhat underdeveloped, which is perfect for the reader to imagine themselves in the role. But for a film, James Bond had to become more defined, and crucially, relatable. As detailed in the Paul Duncan book The James Bond Archives, Cubby Broccoli specifically wanted Connery’s Bond to feel more down-to-earth than the Bond of the books, saying: “…we never intended to play Sean Connery exactly as Fleming’s Bond. The whole point about having Sean in the role, with his strong physical magnetism and overtones of a truck driver…was…the audience could feel like there was a guy up there like them.”

Polygon‘s staff responds to letters asking for very specific horror recommendations:

Dear Polygon,

Being completely honest, my fave horror movies are the ones that have some descent into madness. […] So please hit me with your weirdest!

—Jupiter

[…] Possession [1981] is directed by Andrzej Żuławski, a Polish filmmaker and an absolute master of very messed-up love stories, and of people losing their minds over love (or something that looks kind of like love if you squint).

And a trio of book-centered articles!

After Hilary Mantel’s death, Leo Robson examines how her fiction draws from and finds the gaps in history:

Wood argues that Mantel “proceeds as if the past five hundred years were a relatively trivial interval in the annals of human motivation.” Mantel would probably have agreed. She believed in psychoanalysis as an explanatory framework. She didn’t see the need for a micro-sociology to explain to a contemporary audience why her characters from the sixteenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries cared about what they cared about. But she had a far greater investment in the historical detail as detail than a sceptic of historical fiction might allow. Mantel went as far as saying that she only “became a novelist because I thought I had missed my chance to become a historian,” and that she only wrote a contemporary novel – as she proceeded to do in the early 1980s, after the rejection of the earlier version of A Place of Greater Safety – as “a way to get a publisher.” Her heart, she said “lay with historical fiction,” and when this was revealed, her approach was avidly and specifically history-minded.

At Public Books, Melanie Walsh introduces a new project focusing on how to use data to understand literature and publishing – and how even the most basic data about book sales is hidden from the public:

The toxic combination of this data’s power in the industry and its secretive inaccessibility to those beyond the industry reveals a broader problem. If we want to understand the contemporary literary world, we need better book data. And we need this data to be free, open, and interoperable. …To people who care about literature, data is often seen as a neoliberal bogeyman, the very antithesis of literature and possibly even what’s ruining literature. Plus, people tend to think that data is boring. To be fair, data is sometimes a neoliberal bogeyman, it is sometimes boring, and it may in fact be making literature more boring (more on that to come, too). But that’s precisely why we need to pay attention to it.

And in advance of the awarding of the Nobel Prize for Literature, Alex Shephard at The New Republic offered a hilarious if wildly inaccurate handicapping of the field, with some appreciation for the eventual winner:

Of course, there are even further-flung political obsessions in which Nobel watchers can spend several hundred hours entangled. Could the Swedish Academy award a Ukrainian writer as an act of solidarity in opposition to Russia’s flailing invasion? Could it give to all those people who tweet long threads about Russian tank failures or to Volodymyr Zelenskiy, for his shirts? Perhaps the committee could make a principled statement about reproductive rights by honoring Annie Ernaux, whose Happening is one of the most profound and moving accounts of the horrors that attend the illegalization of abortion? (Ernaux is also notable for her contribution to France’s most important literary export: books about having an obsessive affair with someone who barely talks to you.) … [Ernaux is] a perennial front-runner who never quite crosses the line. As a memoirist, she could be seen as a departure for the Academy, but in the age of autofiction, anything goes. Anyway, if Churchill could win for his autobiographical work If I Did It (and by “It” I Mean the Bengal Famine), Ernaux can surely win for her searing excavations of her own past.