The FAR is really, truly hip to youth culture and not faking it. We’re into TikTok, obscure Disney animation, Muppet subversion and Nordic anarchist literature. You know, for kids! And of course, being young and all, we remember the process of birth and are interested in films about the same.

Thanks to scb0212 for contributing, may he remain forever young. Send articles throughout the next week to ploughmanplods [at] gmail, post articles from the past week for discussion below, and Have a Happy Friday, Kids.

After recent success, it’s easy to forget Disney’s first stab at a computer-animated feature was the buried and forgotten Chicken Little. Drew Taylor digs it back up at Collider.

Insurance giant Aflac offered the production millions of dollars if they put its mascot bird in the background of certain scenes. “Mark just said, ‘No I’m not going to do that,’” Fullmer said. Executive interference was constant. “David Stainton had some bad ideas. I’ll just leave it at that,” Fullmer remarked. Dindal remembered a disastrous screening where they got 75 notes from the studio afterwards. “It was overwhelming. But at the same time I remember going, ‘Okay let’s go through them.’ We never reached a point when we said, ‘Enough already,’” Dindal said.

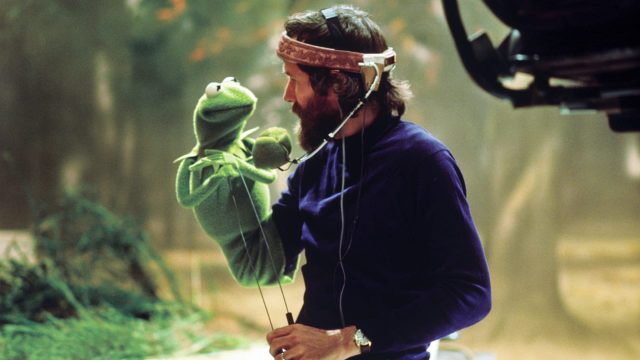

This article from Merrit Micham at Bright Wall/Dark Room is called “The Muppets: Sex and Violence.” If you need more than that, I don’t know what to tell you.

Contemporary chaos may be draining, but there’s a different vein of chaos that I dearly miss: uncontrollable laughter, inappropriate glee, and late night talks that descend into a surreal madness where everything is funny. The chaos of possibility. Silliness. Nonsense. And it’s this love of chaos that early performances of The Muppets capture like lightning in a bottle. Jim Henson’s individuality and ingenuity combined with low-budget, quick-deadline circumstances to create a chemical reaction of gleeful violence, manic stupidity, and existential weirdness that is a balm to any tired, cynical soul. In a world where chaos is constantly grating at our collective sanity, the Muppets provide an antidote via nonsense of their own, using indomitable positivity to prove that there’s an optimistic flip-side to disorder.

Kyle Chayka provides “an ekphrasis on TikTok, while it’s still fresh,” and describes a tranquil personalized experience and/or window into future machine-controlled hellscape:

The passivity induces a hypnotized flow state in the user. You don’t have to think, only react. The content often reinforces this thoughtlessness. It’s ephemera, fragments of the human mundane; Rube Goldberg machines are very popular. Sure, you can learn about food or news, but the most essentially TikTok thing I’ve seen in the past few days is a video of a young man who took a giant ball he made of beige rubber bands to an abandoned industrial site and bounced it around, off ledges and down cement steps, in the violet haze of early dusk. The clip is calm and quiet but also surreal, like a piece of video art you might watch for 15 minutes in a gallery. It has no symbolism, no story arc, only a pleasant absence of meaning and the brain-tickling pleasure of the ball gently squishing when it hits a surface, like an alien exploring the earth, unaccustomed to gravity.

Clayton Davis at Variety talks to Venessa Kirby and Ellen Burstyn – Netflixes other mother-daughter Oscar drama pair – about their roles in Kornél Mundruczó’s (White God) English-language debut:

Burstyn: I always draw from personal experiences. It’s just part of what we do. I don’t know how to not do that. She’s a funny type of character [Elizabeth]. The story Kata wrote about how she was born, with the Holocaust aspect of the film, is from Kata’s family. The idea of being held upside down by your feet and the doctor saying that if she picks up her head, she’ll survive. That’s such a…deeply moving concept how one comes into the world. With the will to live, despite the frail condition of the body. It’s so moving to me.

Finally, Richard W. Orange tells Aeon about the madness Pippi Longstocking and the Moomins brought to children’s literature after Europe had been ravaged by war and propaganda:

The thrill of Pippi is how all this turns around. She sleeps with her feet on the pillow, she rolls out cookie dough on the kitchen floor, and makes pancakes by tossing eggs – shells and all – into a bowl. She stays up late into the night tending her garden. She is a virtuoso liar, spinning tall and inventive tales about the peoples she has encountered in far-flung lands. […] Perhaps to her surprise, Pippi escaped criticism for a year before John Landquist, a prominent literature professor and critic, attacked the books as disgustingly amoral. ‘No normal child eats up a whole cake at a coffee party,’ he railed. ‘It is suggestive of a diseased imagination or of compulsive-obsessive behaviour.’ As the debate raged in Sweden’s newspapers, Lindgren was silent, but in interviews she consistently argued that Pippi was less a role model than a sort of release valve. ‘Pippi satisfies children’s dream of having power,’ she later wrote, ‘and I believe that somewhere in that is the key to her popularity.’