This Week You Will Hear the Music of:

- strike (one)

- strike (two)

- strike (three – we’re out (of strike articles))

- yelling producers (from the past)

- frickin Owl City (sorry)

- the masses!

Thanks to scb0212, C.M. Crockford, and Miller for their melodious contributions! Send articles throughout the next week to ploughmanplods [at] gmail, post articles from the past week below for discussion, and Have a Happy Friday!

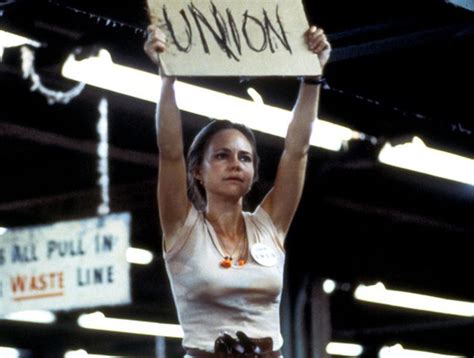

As the WGA strike continues, The Decider’s Walter Chaw writes about labor movies of years gone by – and posits why they’ve disappeared from studio production lists:

While each of these films can be read as metaphors for issues that remain unresolved, as period pieces they’re more likely to be enjoyed — or possibly dismissed — as artifacts of a less enlightened age suffering indignities modern workers no longer have to endure. The powers that be would like every inch conceded to be the last ground given, and films about progressive issues of any sort have a tendency to make those who could make a difference feel as though they’d already given at the proverbial office.

A familiar face covers the strike in Philadelphia – C. M. Crockford reports for Cinespeak:

As TV screenwriter Sam Watson pointed out on Twitter, one marching song felt “very Philly” in its blunt, defiant message:

“No one pays us, no one pays us

no one pays us and we care,

we’re from Philly, fuckin’ Philly,

fuckin’ pay us because we care.”

Hamilton Nolan decries the latest high-profile scab in the ongoing WGA strike – Barack Obama:

You can quibble or be pedantic about the exact contours of our picket line and the specific obligations of non-members with respect to our strike, but it is clear here that Obama violated the spirit of the strike by carrying on with his promotional duties for Netflix right now, something that a zillion very fancy and powerful Hollywood showrunners have stopped doing in order to help the union. It is equally clear that the simple gesture of not doing that single promotional event would have been a profound act of solidarity with a union on strike. And Obama, I assure you, has more leverage to tell the company “I’m not gonna do this now” than anyone else in the entire industry. Netflix will not fire him. I promise. He had very little to lose by making the tiny gesture of not doing this promotional event. He just didn’t care. The good thing, I guess, is that rather than typing out the entire disappointing history of the Obama administration and organized labor, you can just say, “Imagine a guy who would get paid millions of dollars to make a show called ‘Working’ in homage to Studs Terkel, and then cross a picket line for it.” That is as good a summary as you will find.

At Variety, Maureen Ryan goes deep into the behind-the-scenes dysfunction that became the norm on the groundbreaking series Lost:

Perrineau had come up against one of the unspoken rules in the entertainment business: You don’t question the dudes in charge. Lostemployee Gretchen added that in her experience, under Lindelof and Cuse, the workplace grew less flexible and more autocratic and uncomfortable: “Toward the end of the second season, after all the accolades came, I could see where it could be unbearable for some people to be there,” especially as an industry norm she was familiar with—that those ruling a workplace could be “vindictive” at will—was cemented into place. Lindelof and Cuse had the power to hire and fire, no matter the reason, she noted. “And they used it.”

At Stereogum, Tom Breihan’s journey through Billboard Number 1 pop hits runs into Owl City’s rage-inducing “Fireflies”:

“Fireflies,” the one giant hit from the bleepy-mewly one-man band Owl City, does not make me want to gargle blood or vomit ash. It might be worse than that. I don’t like the person that I become when I listen to “Fireflies.” “Fireflies” is like a magical spell that instantly summons my inner playground bully. I don’t want to burn “Fireflies” in a bone-bleaching, soul-cleansing inferno. The song doesn’t inspire that level of passion in me. I just want to give this song a wedgie and throw its hat in a toilet. I would like to avoid that kind of activity, metaphorical or otherwise, in this column. I’ll do my best. I can’t promise that I’ll succeed.

And in his newsletter Element X, Steve MacFarlane goes long on list-making, Letterboxd and the weight and restrictions of history:

So while the leveling of the playing field for thoughtful criticism continues apace, wishing in kind for a different Letterboxd would be not just naïve but ahistorical; counterproductive. It’s hard to tell if the issue is that these extremely online cinephiles are uninformed or too informed. Running these drills takes my mind in weird directions, like: who is the ideal “virgin” watcher of a movie I’m programming? How do I sell an obscure film to people without burying them in historical/cultural/aesthetic context? Or without bastardizing/obfuscating the actual experience of watching it? How will I attract the attention of people who aren’t already lost in the cinephile/Letterboxd sauce? Hopefully the movie argues for itself well enough, but you still need someone plopped down in front of it before hitting the Play button. These questions aren’t a side nuisance of programming, exhibition or distribution; answering them is the job.