The FAR follows new trails into territories good, bad and ugly for Western heroes, pandemic stories, rightwing comedy, cyberpunk games, and live music analysis.

Thanks to scb0212 for contributing this week, happy trails to him. Send articles throughout the week to ploughmanplods [at] gmail, post articles from the past week below for discussion, and Have a Happy Friday.

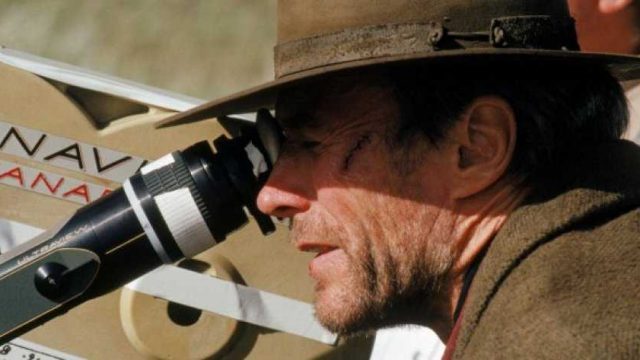

At Reverse Shot, Julian Allen takes an outsider’s perspective on what Unforgiven meant for Clint Eastwood’s persona and how that persona has borrowed from and given back to American myths:

Over the years, an irresolvable dichotomy would develop between his humane, upstanding American decency and his apparent macho predilection for frontier justice. This would endure, through the Dirty Harry controversies, the debates in the ’70s and ’80s about Eastwood’s worth as a director, through his critical peak in the 1990s, all the way to the idiocratic tyranny of the 21st century’s Twitter landscape and its gradual, drip-drip extinguishment of moral and political complexity from the cinephilic vocabulary. Eastwood calls himself a libertarian (is there a more “Old West” concept than this?) while his favorite movie is William Wellman’s 1943 leftist, anti-death penalty rule-of-law classic The Ox-Bow Incident, starring Henry Fonda in a precursor to his role in Twelve Angry Men. It seems that when it comes to an artist thinking, acting and being more than one thing in America, a man’s got to know his limitations.

The Ringer‘s Miles Surrey reviews the available narrative films shot during and involving the pandemic lockdowns:

Like the underrated Unfriended and its sequel, Host works best when viewed on a laptop: The entire film captures the Zoom desktop aesthetic so authentically that I found myself trying to move the on-screen cursor more than once. The feeling that you’ve somehow intruded on an actual Zoom call is, obviously, a lot more unsettling once mysterious thuds and blink-and-you’ll-miss-it demonic entities interrupt proceedings. The scares, too, are fiendishly spun out of this setup: At one point, a character spams the chat because her face is repeatedly being smashed into the keyboard. That Host ends with Zoom notifying the participants that they’ll need to upgrade if they want more time on the call shows that Savage has made the most of his film’s COVID-imposed difficulties, instead of being hindered by the constraints. It’s no small feat, but with Host, the quarantine era has its own Blair Witch Project.

Hunter French writes in The New Republic about how the comedy industry created a platform and support system for an emerging alt-right:

T.J. Miller, the comedian who has been thoroughly disgraced by allegations of sexual assault and transphobia but is somehow still at it, recently made an apt observation about how power works in mass culture. “Standups understand this: If you empower your audience, they’re much more likely to pay you again to support you,” he told comedian Bobby Lee. “The audience wants to be empowered.” He was critiquing Hollywood’s reliance on stale film franchises he believes audiences don’t like, but the analysis applies to comedy, too. You empower an audience by giving them what they want. The power they give you in return is their trust, their loyalty, their willingness to fight for you. The relationship between an entertainer and his audience isn’t all that different from the one between a political leader and his movement.

For Input Chan Khee Hoon talks about cyberpunk’s roots in Western fears and stereotypes of East Asian influence, and highlights new games pushing the edges of the genre:

For a genre noted for its futuristic, dystopian themes, cyberpunk’s stories remain a collection of glossy but dated tropes from the ’80s. But many cyberpunk worlds conjured by Asian developers, such as Mark Fillion from Singaporean studio General Interactive Co., try to move past these conventions to present a perspective that’s rooted in the ongoing, but equally alarming, issues of the present. That, in a nutshell, was the impetus for his studio’s game Chinatown Detective Agency. “What I loved most about the genre were the social aspects — the great divide of the social classes amplified by technology,” says Fillion, although he adds that that many cyberpunk tales are still rather derivative. “I think we’re still mesmerized by the spectacle of the cyberpunk future and don’t feel a need to really rethink the genre.” A portrayal of the not-so-distant cyberpunk dystopia of Singapore, Chinatown Detective Agency features updated, yet recognizable touchstones of the country, such as its cuisine and locations — a much welcomed extension to the mostly static milieu of cyberpunk.

While we wait for live music to become a thing again, The Pudding has created an interactive tool for comparing the studio and live performances of songs using metrics like energy, tempo and instrumentation. Kat Wilson and Kevin Litman-Navarro report:

For instance, Bob Dylan’s Blowin’ in the Wind doesn’t exactly come to mind as the encore to end a cross country stadium tour. The folk ballad is typically sung at a slow, ticking rate; it sounds almost like a lullaby. Dylan metronomically recites the lyrics over a simple acoustic strumming pattern, only pausing for a short, intimate, harmonica break in the middle. When analyzing the data, we noticed that the live-recorded version of the song, off of Before the Flood, is, by contrast, a frenzied, five-minute celebration. […] In this version, fans cheer, and the drums pick up in the background as you hear Dylan’s voice creak over the mic. A guitar solo halfway through replaces Dylan’s studio harmonica, and almost ten seconds of applause linger on as he shouts “Thank you, Goodnight!” It’s as if, over the backdrop of a nation closer to the end of the Vietnam War that first inspired the song, the lyrics take on a different tone.