I first saw Dazed and Confused 11 years ago, in the summer of 2013; it was my introduction to Richard Linklater ― sadly, I had lived a School of Rock-free childhood ― and I found it both enjoyable and underwhelming: its disposition towards its setting seemed too uncritically sweet and nostalgic, jarringly so when it came to the cheerful high school hazing scenes, and it didn’t seem to do enough to get me especially attached to anyone onscreen. I might not have seen it again for a long time, but Linklater’s designation of 2016’s Everybody Wants Some!! as a “spiritual sequel” prompted a second look, during which I suddenly found myself in love with the film before its opening credits even ended. Its many characters, “caught” in quick snippets in and around their school to the tune of “Sweet Emotion,” were instantly as familiar and comfortable to observe as old friends, and the film as a whole extraordinarily welcoming and rich, like reliving a party where I no longer felt like a stranger. It then became an early-summer staple, and a film I still call my favorite; I’ve yet to see anything that matches its creation of an onscreen space that’s so idealized and lived-in at the same time, and so alive to all the promises contained within it.

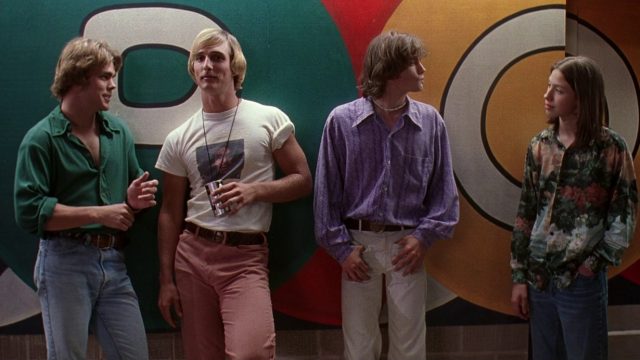

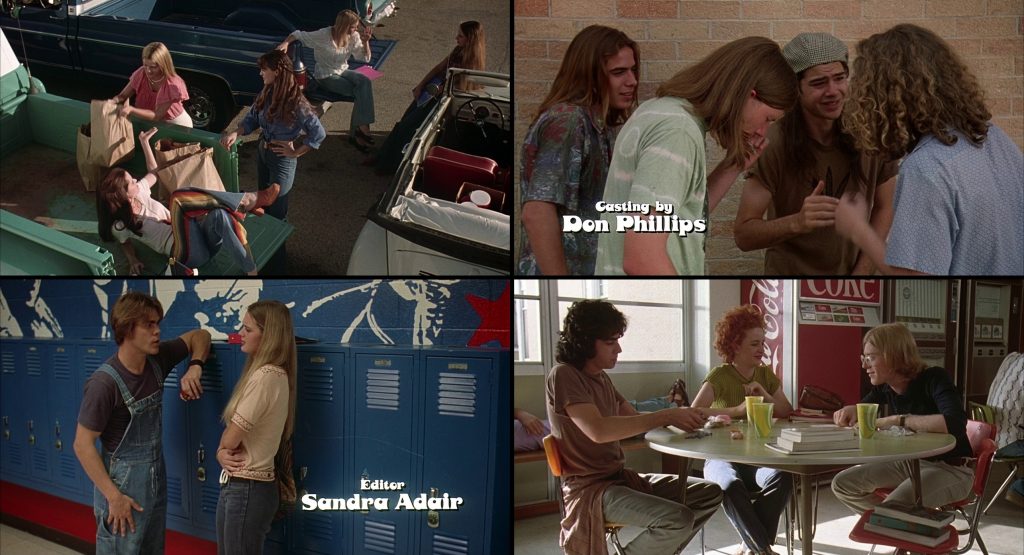

What was it about that intro, and its seemingly simple sequence of images, that made me have such an overpowering reaction to it the second time around? The answer, I now realize, is hidden in plain sight: people are already together, and already visibly immersed in some activity ― a conversation, a smoke, a card game ― that began before the film did. It’s a simple trick, and by no means unique to Linklater, but neither is it obvious or all that commonplace, at least in the way it’s done here: getting dropped without ceremony into a situation is one thing, getting dropped into an environment that’s clearly significant yet appears to be living its own life, populated but offering up no identification figure, is different. In an instant, it establishes the sense that the film’s world is not constructed, but existed long before anyone thought to turn a camera on. There is no introduction, no arrival, no getting the ball rolling. Some characters stand out more than others, but at this point they’re all anonymous and implicitly equalized; there’s no telling who we’re going to get to know, and how closely, and who we aren’t ― which means that once some characters do start to become more prominent than others, it doesn’t feel calculated, and preserves the sense of people-watching. It’s lifelike spontaneity achieved so carefully that you have to stop to even notice the work.

The date is 28 May 1976, the place an unnamed Texas town (based on Huntsville, where the director spent his own adolescence) ― another combination of specificity and generality ― and the local teens kill time waiting for the final day of school to be over, endure painful initiation rituals, then ― as the night falls ― drive around, drink, smoke, play pool, listen to music, cross each other’s paths, talk about things light and heavy, find themselves involved in and witnessing assorted small dramas. The film lives alongside them, picking things up on the fly and seeming to have endless room for human presence; there are between two and three dozen prominent characters, all instinctively recognizable as types from the moment they appear yet portrayed with ever-present individuality by one of the most perfect ensemble casts ever brought together. There’s no overarching goal beyond chasing a good time and no pursuits of anything life-changing, but there is immediacy: at every point in time, everyone is entirely, unselfconsciously immersed in whatever happens to be going on, and their behavior with one another is the movie. There is no greater reward in Linklater’s films than human connection, and here, all spaces shared by people form a kind of unified field that the film can freely roam and shape itself out of.

The choice of when the film is set matters beyond just providing an excuse to show a bunch of partying. As another school year ends and summer begins, the kids become free of set daily routines and open to a slightly new life, with no one knowing exactly where this particular day might take them. Linklater plants numerous destinations and threads to be followed ― a big house party planned for the night, a “no drugs and alcohol” pledge the athletes are required to sign, several characters’ personal plans and resolutions for the day ― that are just present enough to set a course, but are also plausibly buried in a sea of casual incident and sometimes unexpectedly changed by it. The party ends up being busted, leaving everyone to improvise; the pledge and what it represents becomes a source of in-jokes and a way of illuminating different kids’ response to authority; groups are formed and split up; set-ups lead to payoffs, but when, where, and how that will happen are open questions.

Thus locked within a 24-hour timeframe and tracking numerous individual journeys, Dazed and Confused is structured, but it never feels beholden to a structure. It has character development, but what it’s really about is character revelation: as these young people keep finding themselves in new places and situations, they get a chance to show something new of who they are, and build on what we already know about them, with any line, gesture, action, or reaction. As in the Before films and Boyhood, this slice of time is all they have, and it’s rushing forward while they barely keep up; Linklater and his longtime and indispensable editor, Sandra Adair, operate on the principle that the value of a moment comes from how fleeting it is, and Dazed in particular is ruthlessly compressed. This sense is intensified by the characters themselves who, in their youthful restlessness, never stick around one place for too long, and are forever walking or driving somewhere. (Movement and progression ― the process of getting somewhere, both physically and in interpersonal relationships ― is vital in Linklater’s films; it probably isn’t a coincidence that his rare depictions of actual prolonged animosity or conflict ― 1996’s bitter, Eric Bogosian-authored SubUrbia, 2001’s DV experiment Tape, and the last section of Before Midnight ― are based on location-bound plays and/or take place in hotel rooms that the characters can’t leave and in which they become increasingly like caged animals.)

And so the pleasures of Dazed and Confused have to do, above all, with the specificity of every individual ephemeral moment in time, all of which flow with present-tense vividness while simultaneously possessing the plucked-out-of-time quality of future memories. The orange 1970 Pontiac languidly turning a corner in slow motion in the opening shot, the wind and the rising sun playing with Joey Lauren Adams’ hair in the final scene ― and, in between, the communal spaces and energies floating within them, the stray bits of exceptionally detailed set design and overheard dialogue, the actions and consequences that the film is conscious of without the characters having to be. Jodi (Michelle Burke) picking Sabrina (Christine Hinojosa) out of a crowd and gently intimidating her into saying yes to a hazing ritual while asking for her own little brother Mitch (Wiley Wiggins) to get softer treatment, and inadvertently setting both of the younger kids onto separate journeys. Hirschfelder (Jeremy Fox) being insistently called away from the unnamed girl he’s been making out with, and the camera staying with her for a few moments, sympathetic to her disappointment. Kaye (Christine Harnos) criticizing Gilligan’s Island as a male fantasy, and not being understood. “Whose bowling ball is this?”, not the first question you’d expect from someone who’d just gotten into the backseat of a car. The view of a stadium in the soft light of dusk, and a high schooler politely navigating small talk about football with an elderly couple who were probably born in the 19th century. “Tamperin’ with mailboxes is a felony aw-fence.” The effortlessly charismatic ramblings of Rory Cochrane’s stoner icon Slater, but also his vulnerability when he shouts, “Check you later!” to a carful of girls and is promptly made fun of for it. A cheerful delivery guy bringing kegs of beer around too early, leading to the party getting busted ― and, hours later, Matthew McConaughey’s confident deadpan drawl as he responds: “Not to worry. There’s a new fiesta in the making as we speak…”

Two years ago, the now 60-something Linklater joined the conspicuous number of aging filmmakers who’ve recently put their memories of growing up on the screen with Apollo 10 ½: A Space Age Childhood, whose animated form allowed it to be uncompromising, its entire first half constituting a breathless recounting of every single throwaway detail of life in late ‘60s Texas that could possibly fit into the frame and in the voiceover narration. It gets practically assaultive, and behind it, you can sense a burning desire — not to say desperation — to preserve and share the things an individual was formed by before they’ve been lost forever. Dazed and Confused now exists, in some ways, as the opposite of that film: a live-action, glancing look at the past by a young director who’s not yet too far removed from it and is revisiting rather than holding on to it. There was no such wave of autobiographical movies in the early ‘90s as in the past several years, but it says something about the lure of going home again that, around the same time, filmmakers as radically different as Linklater, the late, great Terence Davies (The Long Day Closes) and Spike Lee (Crooklyn) were all recapturing the air they breathed growing up.

Linklater’s reputation as a good-natured, easy-going humanist with a love for philosophical spitballing and an antipathy for contrived conflict can obscure how easily and assuredly his work registers the darker aspects of his characters’ lives. Watching Slacker again for the first time in years, I was struck by the number of conspiratorial or outright paranoid voices among its baton-passing characters, which made it play in a new light in the time of intensified, widely broadcast conspiracies and misinformation. The scene that has stuck with me the most from my revisit of Boyhood is Mason Jr. happily riding his bike down the street only to turn and find his mom lying face-down on the ground in their yard, her abusive boyfriend standing over her. Linklater’s true-story-based films don’t tend to be inspirational: in Bernie, all that fabled human connection and generosity brings together two people who never should have met and ultimately leads to murder; 2006’s overlooked Fast Food Nation is a socially conscious, blowing-the-lid-off-malpractice drama that starts off breezy and good-humored before revealing an underlying despair when its characters find themselves powerless in the face of the system. Then there is all the messy, ugly emotion that comes to the surface in Before Sunset and finally takes over in Before Midnight, as one of cinema’s great romances progresses from bliss to hard work. And his latest work to premiere — not Hit Man, but the HBO documentary God Save Texas: Hometown Prison — makes the struggle between hope and despair its very subject, as Linklater returns to Huntsville and reckons with its past and the present as a place where the prison system has become the largest industry, and with how that has affected the community he has deep-rooted ties to.

Dazed and Confused complicates the good vibes with the aforementioned hazing, which was indeed practiced where the director grew up and which he makes as casual and natural a part of the film as anything else, which it took me a while to recognize as its own statement rather than carelessness. The spectacle of seniors chasing freshmen around to paddle them or (in the case of girls) pelt them with eggs, flour and ketchup under the baking sun is at once self-evidently absurd and unquestioned by the community; some participants, like Jodi or Adams’ Simone, recognize it as performative (“I’m supposed to be being a bitch”), others, like Ben Affleck’s O’Bannion and Parker Posey’s Darla, gleefully embrace the opportunity to bully everyone in sight, and still others seem to fall somewhere in the middle, neither apologetic nor nasty but going with the accepted norm. Linklater isn’t after anything so simple as making fun of or shaking his head at the past from a more civilized vantage point. Instead, he himself risks raising a sympathetic viewer’s eyebrow by e.g. blaring “No More Mr. Nice Guy” over the scene of Mitch getting viciously paddled by O’Bannion and making it as much about the latter’s delight as about the former’s pain. The presence of both perspectives isn’t there to downplay one and excuse the other but to register them, in real time, as two opposite yet equally true personal experiences of the same thing.

In another telling, layered moment, one of the film’s most charming characters, Sasha Jenson’s affable jock Don Dawson, crosses an unspoken line and teases a freshman girl (Priscilla Kinser) who’s been brought to him with, “Do you spit or swallow?”; “That is so degrading,” responds Slater next to him, but can’t suppress a guilty laugh all the same while the girl is led away, never to be seen again. Being a teenager means exhibiting this kind of spontaneous cruelty, being on the other side of it, adopting it, becoming conscious of it in yourself and your peers, ignoring and addressing it.

The one limitation of Dazed and Confused is that, despite initial attempts at balance, it is finally skewed to the male perspective, something Linklater himself was disappointed by at the time. But if the majority of the characters who wind up with character arcs and catharses are boys, the film is also clear-eyed about the ways their charm co-exists with a capacity for casual dehumanization. Similarly to the way a bleak film can get a jolt of power from characters showing simple kindness, the aggression in Dazed and Confused is more striking, in part, because it’s enfolded into the good times (and in fact is part of some of the characters’ idea of having a good time), and Linklater is keeping things varied within boundaries. He knows the film would become unbalanced with the addition of seriously traumatic violence or hatred (the valuable deleted scenes do include the most intense character, Cole Hauser’s Benny, launching into a racist tirade against the Vietnamese, along with a separate, tossed-off revelation that he is being physically abused at home), but the empathy towards every person on screen — all of whom the film understands as people making their first steps in a world of oppressive systems and rules they’ll have inherited from the previous generations — isn’t any less meaningful for it. It is both the foundation and the result of the patient observation of these characters as their likable as well as objectionable selves, and thus a sign of rare discipline.

A simpler, more immediate way of looking at things is that pain and joy can be intertwined, the former making the latter more valuable; so Mitch is reassured by Pink (Jason London), who reminisces about how seniors busted the hell out of him and his fellow freshmen, then took them under their wing to complete the rite of passage. With some luck, there can be room for you to decide what you want to take out of an unpleasant experience; as Mitch and Sabrina, who had gone through the hazing without getting any demeaning sexual questions thrown at her, agree to join the partying and explore this new world they’re offered, Dazed and Confused heads alongside them into the warm summer night. What it finds there is, at its best, a quotidian utopia, in which — to quote from Don’s climactic moment of reflection — people try to have as much fun as they can “while being stuck in this place”. The climactic party in a park serves as something like a fictional recreation of Linklater and cinematographer Lee Daniel’s first known work, the short music documentary Woodshock; besides bringing their work up to that point full circle, this further reconciles their impulses as entertainers and documentarians. That the arrival to this everyday place is so ecstatic — a smash cut from a dialogue exchange to everyone speeding up the road while KISS’ “Rock and Roll All Nite” takes over the soundtrack — makes it one of numerous Dazed-in-a-nutshell moments.

By the film’s second half, scenes no longer follow each other so much as stack on top of each other; already-established characters may become extras, effortlessly enriching a moment without even having to do anything, while those who had barely been glimpsed before may unexpectedly come into focus. Some of this is the result of the dynamics that developed on set, where some actors weren’t fitting in and others (like McConaughey, who is first seen 11 minutes before he speaks) showed they had far more to offer than had been planned; regardless, Linklater and his collaborators did an expert job of engineering a space that could sustain rapid shifts in emphasis and tone in the first place, without the film straining or devolving into random chaos even for a moment. Put together in one space a group of people who are both bound together and distinctive — like high school students — and the contrasts and dynamics between them can create their own depth, the film bouncing between them like a ball inside one of Linklater’s beloved pinball machines. In one of my favorite low-key scenes, about half a dozen small individual stories converge outside the pool hall within a space of less than two minutes, with every single interaction — even dialogue-free; see the body language between Adams and London — either revealing or deepening a relationship.

There are different sides to lived experience; being founded on this simple truth keeps Dazed and Confused from ever becoming simplistic or sentimental, and allows it to be an open film about being open to life. Freedom means uncertainty, and vice versa. Coming up with ways to have fun in a small town is a consequence of being stuck there in the first place. The constant forward motion and progression means that no magical moment can be stopped and bottled. A night of partying brings people together — and also inevitably separates them, setting everyone on their own path.

The film is devoid of melodrama or over-the-top set-pieces that are a staple of teen comedies, and yet its characters experience things they’ll likely always remember, from buying alcohol for the first time and getting threatened with guns to finding their first love and meeting people who could become their friends for one night or for a lifetime. O’Bannion gets triumphantly owned by those he had himself humiliated (and the camera stays with him for a minute too, watching him lash out in helpless rage). Introverted best friends Mike (Adam Goldberg) and Tony (Anthony Rapp) agree that what they need is a “good old worthwhile visceral experience,” but still can hardly anticipate that by dawn, one of them will have made an enemy and initiated a (serious and very painful) fight — just to not “feel like a little ineffectual nothing for the rest of my life” — while the other’s acquaintance with the temperamentally similar Sabrina will have become the start of a relationship. What makes Linklater’s cinema so moving to me is that it is, above everything else, one of possibility.

The director has openly admitted that he initially intended for Dazed and Confused to be an “anti-nostalgic” movie, which didn’t work out: too many things that ended up on screen looked fun and attractive no matter what. Yet their transience, as well as their casual proximity to pain and embarrassment, lead to something more than a simply nostalgic or anti-nostalgic movie: a movie about what nostalgia is born out of, about how simultaneously mundane and special it is that we were here. On screen, May 28th, 1976 is not history; it is today, and then, before you know it, it has become yesterday. No one knows what their future will be — but the sun is rising, and the road is clear, and they’re not alone.