Dig a hole, cover it with a couple of doors and then throw three feet of dirt on top. It’s the dirt that does it. . . .Everybody’s going to make it if there are enough shovels to go around. (T. K. Jones, Deputy Under Secretary of Defense for Strategic Nuclear Forces, describing how to survive a nuclear attack in 1981.)

When those lines appeared and began to be shared among people (a 1980s proto-meme), they inspired a deep horror among those of us living in the Cold War, the sense that those in power were increasingly beginning to consider a nuclear war a possibility, even a useful one. (Jones said that if America adopted “Russian methods” of defending people and industry, “recovery times would be two to four years.”) Directly responding to this, writer Barry Hines and director Mick Jackson created a simple, low-budget, made-for-television work of propaganda about a nuclear attack and its aftermath, Threads. It was shown on the BBC in 1984 and on American public television in 1985, and I haven’t been able to forget it for thirty years. (This essay was originally promised to be written for Miller‘s Scarefest series on The Dissolve, um, a year and a half ago. Sorry ’bout that.)

Jackson occupies a strange place in my movie pantheon, having directed two of my favorite and most influential movies, this and, one year later, The Race for the Double Helix (still the best movie ever made about science) for the BBC and then heading to Hollywood and making such works as L. A. Story, The Bodyguard, and Volcano (practically the anti-Threads). On both of these BBC films, he worked within the budget and language and crafted two works that are anonymous and unforgettable.

After a nature documentary-like opening (spider spinning a web), Threads launches into what looks like a domestic drama, with Ruth (Karen Meagher) and Jimmy (Reece Dinsdale) talking in a parked car overlooking Sheffield. Ruth will get pregnant here, and that creates one throughline for the first hour and links to the last shot. Ruth and Jimmy confronting her pregnancy, deciding to get married, and renting an apartment provide a good storytelling anchor, allowing us to meet and follow both families and see the escalation towards war entirely from their perspective–no meetings of world leaders here, no battle sequences, only reports of both on the news. At times, this feels like an offshoot of the genetic line that gave us the Plucky British Working Class comedy-dramas of the 1990s; Sheffield was the setting of The Full Monty too.

Threads presents itself not quite as a fake documentary; “domestic drama occasionally interrupted by news reports” describes it better. Anyone who watched local news in the 1980s will recognize the style of the latter: words printed on the screen with teletype sound effects; reassuring male voiceover intoning facts (“Over the past several days, the President and his advisors will have only a few hours of rest”); images and shots that show what the voiceover says. It’s a mode of address as direct and cheap as the images, the language of events rather than spectacle, and it saves Jackson and Hines the bother of having to make an aesthetically coherent work; Threads has the coherence of nightly news, not cinema.

That nightly news format (there are in fact several imitation BBC broadcasts here) works well in the run-up to the attack. I am forever a sucker for watching situations spin out of control, from Mission: Impossible to Argo, and Hines crafts a believable scenario where a collision between U.S. and Soviet forces in Iran escalates, step by step, to all-out attack. There was that fear in the Cold War that was like sickness and age–every twinge in the body could be the beginning of your death. Back then, every confrontation could be the first one in the path to annihilation. And with Reagan’s election, there was now a President who seemed determined to have as many confrontations as possible. Given that official memory has decided that Reagan was a genial figurehead–”the Great Communicator”–I’ll take this moment to observe that at the time, he was absolutely, existentially terrifying.

Another plotline begins in the run-up, the officials of Sheffield preparing for attack, gathering together in a bunker, testing radios, making lists of resources, so forth. It’s another aspect where the working-class realism genre helps the feel–everyone here has a job to do and they’re not entirely sure of it. They just don’t have any other choice but to prepare. At times, I remembered that this is all taking place in Britain, which has a much greater commitment to public welfare than America. This country would be in much worse shape.

The simple, even simplistic style sets up the sucker punch of Threads. By the halfway point, we’re set up for more information about nuclear war, maybe more domestic drama as the characters cope with the aftermath. And then Hines and Jackson hit us, first with the attack, a small masterwork of communicating horror through details and editing instead of spectacle. While keeping in the same perspective of domestic life and news report, Jackson cuts together a montage of shock and terrifying detail–a child burned alive, a dying cat, fires everywhere. He uses the fact that the flash arrives before the blast as part of this; he also pulls a classic horror trick, where one blast sets up an even worse one. That’s the feel of the entire attack sequence, where Jackson shows us what we expect and then hits us with something much worse. By 1984, images of buildings blowing apart were part of the popular imagination (certainly they were part of my imagination), and we were ready for that, but we weren’t ready to suddenly see Jimmy’s mother with half her face burnt off.

Brutal as this is, it’s still in the territory of The Day After, a contemporary film (shown on ABC) that showed a nuclear attack on Lawrence, Kansas, and the first few weeks of the aftermath. The Day After shows far more deaths in the nuclear attack (its signature image is people flash-vaporized into skeletons and then disappearing) but doesn’t come close to what Threads does. It’s in the second half that Threads delivers the real blow: The Day After finishes a few weeks after the attack (so does another powerful film on nuclear war, When the Wind Blows), but Threads just keeps going.

This is the aftermath, the entire second half of Threads, and it never backs down. Jimmy was running in the street when the second blast hit and that’s the last we see of him. The officials in their bunker get trapped; they can barely communicate with the outside and when they can, resources can’t be found, other officials can’t be reached, and every time we come back to the bunker, more of them are dead. (When a team in radiation suits finally enters it, they all are.) People die, and we’re not spared the vomit, scars, shit, blood, and rats that accompany them. Even the incongruities help; at one point, I was sure I heard a helicopter and wondered where fuel was found for it, and of course the immediate next thought is “the reality will be so much worse than this.” The sky goes dark; hospitals can’t treat anyone; Ruth gives birth in a barn. At times, Jackson cuts between film and images that look like newspaper photographs, a cinematic presentation of documentary imagery. It heightens the impact without ever breaking the feel.

The style works because for those of us who came of age in the Cold War, nuclear war had a reality that all other disasters didn’t. Unlike the Irwin Allen disaster pictures of the 1970s (Earthquake, The Towering Inferno, The Poseidon Adventure) or his spiritual successor Roland Emmerich’s more recent films (2012, The Day After Tomorrow, Independence Day), Threads isn’t a work of the imagination but of inescapable fact. Formally, these other imaginative works are not about the disaster itself; the disaster serves as the setting for the characters’ journey, usually a romance or a family coming back together. When a real disaster becomes background for a false story, the impact of it gets necessarily lost. That’s why A Night to Remember stomps all over Titanic–the earlier film is actually about the sinking of the Titanic.

Threads presents a real, global, disaster, one that hadn’t happened in 1984 but easily could have. (How easily? This easily.) The details of the dying world that the narrator recites and the screen displays in the second half of Threads are simple, easily understood, and unalterable. Signs for fallout shelters, talk of nuclear winter, the MX missile system, electromagnetic pulses, and the continuing posturing of America and the Soviet Union were all part of the texture of everyday life in 1984 and all Hines and Jackson do here is picture the most straightforward consequences. The end of the world here isn’t an opportunity to create incredible visual effects or a chance to see a nuclear family get back together; in fact, all families disintegrate along with everything else. Disaster porn is the last thing Threads is.

John Hersey’s Hiroshima, written at the beginning of the Cold War, pulls a trick similar to Threads: both works use a conventional, well-known structure (news report for Threads, New Yorker article for Hiroshima) to lead us into the horror. Hersey said “the flat style was deliberate, and I still think I was right to adopt it. . . .A high literary manner, or a show of passion, would have brought me into the story as a mediator; I wanted to avoid such mediation, so the reader’s experience would be a direct as possible.” There was no style there, not even the kind of polished simplicity of Hemingway. Reading it felt like being buried alive, every sentence and detail landing like another thud of dirt on the coffin. (Peter Guralnick’s Careless Love: the Unmaking of Elvis Presley is the only other book that had that impact on me.) Threads has the same feel and it should. There’s no drama here, because drama requires people to make choices that will have consequences and that will not happen here. Nothing anyone does will matter, and all there is to do is record the failure of every action.

The narrative jumps forward on the macrolevel, accelerating through days, months, years, but time slows down here on the microlevel; there’s much less that can be done in the aftermath. Jackson lingers over some images that have a genuine poetry, like the helplessness of Ruth trying to pound grain into flour. In another scene, the camera just looks at Ruth, her newborn daughter, and a few other people around a fire. The previous shot indicates “December 25 Seven months after attack.” No one says anything; Jesus will not come, nor will He even be remembered.

Moving into Ruth’s daughter’s generation, the first born after the attack, the disintegration continues. Language, family, and learning all disappear; there will be no continuity with the past. Children can barely form words, slurring the ones they can. Ruth dies in her twenties, eyes burnt pale by ultraviolet radiation, hair grayed and falling out, and the last thing she hears is her daughter repeating “up. Ruth. Work.” Education is a single videotape and a single television, showing images and words (“dinosaur,” “cat”) that have no connection to this world. The most industry around is children unraveling the clothes of the dead to make rope. Ruth’s daughter joins a small pack of scavenging children, one of which rapes her not long after.

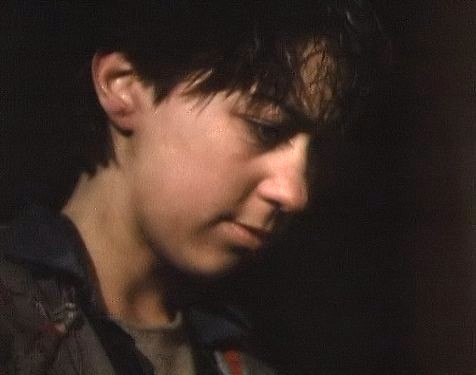

Victoria O’Keefe, playing Ruth’s daughter, gives the best performance here, nearly silent. Her voice, gaze, and body language all declare her as something not from our world; she’s much more alien than The Road Warrior’s Feral Kid from three years before. She’s not stupid, but we can see that without education, her intelligence can’t develop into anything resembling community or civilization. She’s one more way everything is ending. (Six years after Threads, O’Keefe died in a car accident at the age of 21, as if this wasn’t depressing enough.)

Victoria O’Keefe, playing Ruth’s daughter, gives the best performance here, nearly silent. Her voice, gaze, and body language all declare her as something not from our world; she’s much more alien than The Road Warrior’s Feral Kid from three years before. She’s not stupid, but we can see that without education, her intelligence can’t develop into anything resembling community or civilization. She’s one more way everything is ending. (Six years after Threads, O’Keefe died in a car accident at the age of 21, as if this wasn’t depressing enough.)

I wonder sometimes if Threads can ever have the same impact on those that didn’t come of age in the Cold War. Dr. Strangelove still lands, because on the most essential level, it’s about the madness of nuclear war, not the war itself–and that madness is most definitely still with us. Threads was conceived as propaganda, not art, and it may have the limits of propaganda. It comes from a historical moment where nuclear war and the fear of it had a reality that hasn’t been around since; there’s fear of nuclear terrorism now, but not nuclear annihilation.

Threads shows, step by step, a species dying. That is its blunt, brutal power. Horror films work best when they are rooted in something psychological, and the fear here was so close to the surface for those of us who grew up in the Cold War. William Faulkner called it “a general and universal physical fear so long sustained that by now we can even bear it,” the fear not of injury or even death, but of extinction. Cormac McCarthy wrote “where men can’t live gods fare no better,” and that elegantly describes what the end of humanity would mean: whatever transcendence that humans lived with, call it religion, the divine, history, imagination, culture, love, would disappear too, and be as if it never was. We would lose not just our lives but our meaning, not just the future but the past too. The fear was of oblivion, and that’s not the same thing as death.

Horror movies have to have great final shots, something that feels like that last shovelful of dirt, and there is nothing to match the hopelessness of Threads’ final moment. Every other work about the end pulls the punch, stops short, but Threads takes the story all the way. Perhaps thirteen years after the attack, Ruth’s daughter gives birth in what looks like a cow’s stall and we only catch a glimpse of the result, bloody and inert; the word stillborn has never had such force. A nurse (for lack of a better noun) wraps it in paper and gives it to her, and she’s uncomprehending for a moment and the film freezes and cuts to black just as she’s about to scream. When David Chase pulled this sort of cut at the end of The Sopranos, it was puzzling, intellectually challenging, and launched a discussion that still going on, but the meaning here is clear, unmistakable, and absolute. This generation cannot give birth. No more babies will be born; like everything else in Threads, it’s unspectacular and unarguable. The film ends and so does