When Tom Clancy’s first novel, The Hunt for Red October, was released through the tiny Naval Institute Press and became a surprise bestseller, one of the questions ricocheting around Washington was “how did this guy find out so much about submarines, the CIA, the Pentagon, etc.?” to which someone replied “the same way spies do, he went to the library.” All that technical information, however diligently assembled, still needs a plot and characters to anchor it, and Clancy invented his major character right away, and brought him back in nearly every novel since: Marine (out of service with a back injury), stockbroker (the kind who’s ethical, rich, and retired), historian (naval), policeman’s son (so you know this guy’s tough), and occasional CIA analyst (which is what gets him in on the action, every time) Jack Ryan, an uncompromised man in a world defined by compromise, succeeding in everything through technical know-how and American righteousness.

What makes Clancy interesting is that depth of information and the fidelity to it. (He was the writer who introduced me to the awesomeness of fuel-air explosives, for one thing.) Ryan is the archetype of the Reluctant Hero, and often his reluctance comes from working within that fidelity. He can’t be James Bond because Clancy’s universe doesn’t allow for that kind of thing; Ryan never wants to go out into the field and Clancy often orchestrates the plot in order to make that happen. Ryan is also, as Miller noted recently, something unusual in spy heroes: a thorough organization man. (He gets called a Boy Scout three times in the upcoming adaptations, never as a compliment.) Clancy thinks of the CIA and the U. S. Navy as perfect institutions, efficient and devoted to the good, and Ryan happily does his job within and for these institutions; he and his Chief Get Results, and no one in their world is stupid. (Politicians are another matter.) Except for the occasional work like Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy, that’s not what we see in our cinema spies.

Clancy was never the kind of writer you’d call “good” and only rarely would you call him “competent,” but he could craft globe-spanning plots, the kind where the negative buoyancy of a tree in the third chapter pays off in the twenty-eighth. The plotting and detail, though, point up the thinness of the characters and ideology; it only took a few books and the end of the Cold War for him to go full-blown right-wing nutjob,* as Ryan becomes an unelected President who uses smart bombs only against specific people and gets right in the path of an incoming missile and creates an international force against eco-terrorists and reforms the tax code and creates a privately funded anti-terrorism group with a star analyst, Jack Ryan, Jr. (It’s questionable how much actual writing as opposed to franchising Clancy did in his later years, and it’s also questionable how soon after Red October those “later years” started.) Although we’re coming close to thirty years’ worth of Jack Ryan adaptations, none of them are from books after The Sum of All Fears (1993); you don’t want your spy movies to get implausible, ya know.

A weak source doesn’t necessarily mean a bad film, as Mario Puzo could tell you. Each novel provides enough plot and detail for a miniseries, and it’s only now that we’ve got one. Often the first challenge for film adapters is how to strip the book down to 2½ hours and a manageable set of characters, starting with Ryan himself. As you can probably tell by now, he’s a nearly blank slate, allowing for smart actors and directors to scrawl something interesting upon it. Let’s go to the list:

Alec Baldwin (The Hunt for Red October, dir. John McTiernan, 1990) Die Hard got McTiernan this movie, and also assured that his achievement would never be recognized, ‘cuz this is one of the greatest of all action/suspense films, a remarkably old-school product comparable to The Great Escape: an all-star cast of Manly Men doing Manly Things in multiple locations, a collection of disparate activities organized around a clear central plot, the kind of entertainment that promises audiences action, drama, speeches, gunplay, and comedy all in the same evening, and by God, it delivers. The first and still the best Clancy adaptation, it strips the plot down to what’s indispensable and throws out almost all the dialogue (what Larry Ferguson and Donald Stewart replace it with makes this one of the ten most quotable movies of all time, something you would never expect from Clancy) and McTiernan keeps every story and action coherent while carefully accelerating the whole complex machine from start to finish.

Baldwin was halfway between the Nice Guy of Beetlejuice and the Operator of Glengarry Glen Ross and Malice (he’s the same character in both) and just as professionally as Ryan, he knows what to do here: take his corner of the story and lock it down. Like Ryan, Baldwin understands that there are a lot of other people doing different jobs and he just has to do his, not theirs; this is one of the few Baldwin performances where he’s not stealing attention from everyone else. (Possibly the key to adapting Clancy is that Jack Ryan should not be a starring role.) In a movie with so many huge presences (Sean Connery, natch, but also Scott Glenn, Fred Dalton Thompson, Courtney B. Vance, James Earl Jones in his second most Vaderish performance, and because shit somehow wasn’t crazy enough here, Tim Curry), Baldwin lets himself be the supporting player to all of them. In way over his head and a little bemused by that, he makes every scene of his stranger and funnier without ever losing Ryan’s conviction. He is also one damn fine-looking young man (30 Rock used a clip from this for a sublime joke about high-definition) and throws in a Sean Connery impression at the most intense moment. He’s that kind of actor, and it’s that kind of movie.

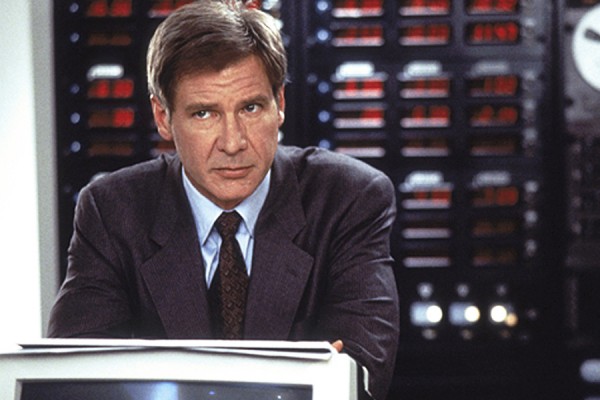

Harrison Ford (Patriot Games and Clear and Present Danger, 1992 and 1994, both dir. Phillip Noyce) In between these movies, late in The Fugitive, you can spot the exact moment when Ford stopped giving a shit about acting for roughly twenty years. (It’s the Explain the Plot scene at the surgeon’s dinner; when he sez “Provasic” I immediately went to the MST3K line “oh great, even I don’t buy it.”) These movies straddle that and there’s a clear decline in his interest between Games and Danger, but they’re recognizably similar performances. Ford looks and acts older than Baldwin but projects a more boyish innocence than Baldwin’s self-amusement; it’s the difference between “I can’t believe this!” and “can you believe this shit?” When Ryan’s peer and rival in Danger (Henry Czerny, playing the same character he would two years later in Mission: Impossible) sticks him with the Boy Scout label, it’s true and it’s a problem: Ford’s Ryan has been around longer than Baldwin’s, so he shouldn’t be more naïve. (Although the Games book happens in Clancy’s continuity before Red October, the movie places it after; James Earl Jones comes back, clearly older.)

Both films broaden the timespan of the action, and give Ryan many scenes with his family (Anne Archer and a young Thora Birch), so they also broaden the character from the straight-up action of Red October. In Games, he and his family are under threat from a rogue faction of the IRA, and especially one of them (Sean Bean) hellbent on revenging his brother; in Danger, they’re just there for character shading. This gives Ford a chance to have more of an emotional range than Baldwin, but it doesn’t make Ryan a more interesting character; his actions and the consequences are still predictable. (We didn’t know then that a Sean Bean character has approximately 0% chance of survival, but clearly Archer and Birch weren’t going to be killed.)

These films are closer to drama than to action, although both have impeccably staged action sequences (the attack on a convoy halfway through Danger is canonical; you can see its influence in True Detective’s “Down Will Come”); the real interest is the Clancian work of tracking the bad guys through networking and technology, and how Ryan gets drawn in to that. Ford does about an equal amount of reacting and asskicking, and Noyce keeps the latter in the believable range for a Marine out of the service and in his fifties. These films (and Ford) aren’t as fun or energetic as Red October (and Baldwin) but they’re still pretty good and worth a look.

Ben Affleck (The Sum of All Fears, 1998, dir. Phil Alden Robinson) Starting with the dental job Michael Bay ordered for him on Armageddon, there was an inexplicable late-1990s push to make Affleck a fully bankable leading man. The Sum of All Fears isn’t an embarrassment on the level of Daredevil (low bar, I know) but it’s thoroughly undistinguished, with little sense of Clancy, Ryan, or even Robinson’s previous and most excellent thriller, Sneakers.

The movie strips the novel down to a single plotline, which is good; but in an effort to restart the franchise, it relocates the timeline to the beginning of Ryan’s career. At this point, he’s still an analyst for the CIA and has a girlfriend rather than a wife. (Her name and profession–Dr. Cathy Mueller, eye surgeon–stays remarkably consistent throughout the series.) Ryan senses that there’s a plot to lead the new Russian premier into war with America; a bomb gets smuggled into Baltimore to be set off at the Super Bowl, and (spoiler) it does, and Ryan has a showdown with the American president to keep him from retaliating–that last scene, which feels completely implausible in the film, in fact comes straight outta Clancy.

Affleck definitely has the young callow Ryan in his range, but little beyond that; he literally doesn’t have the weight he brought to Batman v. Superman. Robinson never moves beyond action-thriller tropes (in Clancy’s wonderfully cranky commentary, he introduces himself with “I wrote the book they ignored for this movie”) so there’s really nothing for Affleck to play. His Ryan comes off even more weak in comparison to the gallery of great character actors around him: James Cromwell as the President, Ciarán Hinds as the Premier, Morgan Freeman in the James Earl Jones role, and best of all, Liev Schreiber as Clancy’s favorite field operative, John Clark. (This role went to Willem Dafoe in Clear and Present Danger.) Schreiber can own a scene by doing nothing but glaring; he plays a better Ryan right next to Affleck’s Ryan.

Chris Pine (Jack Ryan: Shadow Recruit, 2013, dir. Kenneth Branagh) Jack Ryan is essentially a Cold War character, operating in a bipolar world of espionage (and other) professionals, and the audience’s awareness of the complexities of our post-9/11 world made him impossible for our time. Shadow Recruit takes some details of Ryan’s backstory (enlists in Marines, helicopter accident, spinal injury) and shifts them forward to the 00s, but aside from that and bringing Cathy (here played by Keira Knightley) back into the game, this has no connection to Clancy’s works.

The lack of connection doesn’t just mean it’s not a Clancy story; this isn’t Clancy’s world, it’s a world of split-second escapes through back elevators and people realizing terrorist attacks will happen tomorrow and finding said terrorists through almost no evidence while on a plane and, of course, snipers and fistfights and car chases and motorcycle chases. (Branagh films that helicopter accident at the beginning viscerally, painfully well, and then at the end has Ryan go flying out the back of a moving car and landing on concrete with no damage, or loss to Chris Pine’s prettiness.) Thing is, if this had been called Jason Bourne: Shadow Recruit or Ethan Hunt: Shadow Recruit, it would be pretty darn good. Branagh has been a showman from Henry 5 onward and he keeps things driving forward here from the moment Ryan finds that Russian businessman Cherevin (Branagh himself, looking thoroughly Russian) has been concealing something, even if it doesn’t get to the level of momentum of, say, The Peacemaker.

Pine has always been an underrated actor (certainly the most underrated of the Four Chrises); he’s cocky by nature (and he gets a scene here where he basically plays Cocky Chris Pine for Cherevin’s benefit) but can undercut that with uncertainty and fear when necessary. In the film’s best scene, he gets into an abrupt, brutal, ugly fight and kills someone up-close-and-personal for the first time, and Pine does a viscerally good job conveying Ryan’s confusion and raw terror, something new for this character. (No one else would have Ryan forget a password.) All through the film, he feels like a straightforward man who’s chosen to live by deception, who doesn’t like that, and that dislike limits him. (His last scene, with Kevin Costner asking “any chance of wiping that Boy Scout grin off your face?” calls back to Clear and Present Danger and makes more sense here.) It would have been an interesting way to go: take the moral complexity that was always latent in Clancy’s Ryan and play it on the level of action of the Bourne or Mission: Impossible series, but a sequel never materialized.

John Krasinski (Tom Clancy’s Jack Ryan, 2018, series created by Carlton Cuse and Graham Roland) The trick to Krasinski’s performance here is that he doesn’t try to avoid Jim Halpert. (To be fair, The Office set at CIA would be brilliant; you can imagine Jim explaining “here we have the 9/11 hijackers. Over here we have Saddam Hussein. These two things are connected by. . .delusion.”) This Ryan is a few years past Jim in age and maturity (amazing what a good haircut does for the character), works hard rather than slacks off, but still has Jim’s asshole streak, and it comes from the same place: the certainty that he’s better than everyone around him. This series puts some effort into giving something to push back against that, but it’s largely confined to Wendell Pierce (in the James Earl Jones role, which is back to Clancy’s name of James Greer) who’s just not having any of that sheeeeiiiiiiiiiiit; Jack Ryan continually arranges things in favor of Jack Ryan. Like Shadow Recruit, there are a few feints in the direction that Ryan is too smart and pure for everyone’s good (the flashback to the helicopter crash makes it clear that you would never put this guy in the field), but in the end, he’s always right. That’s too bad, because like Kiefer Sutherland in 24 (the gold standard of this century’s action heroes), Krasinski could clearly handle a more damaged and more wrong Ryan.

Cuse and Roland have done more than anyone else in updating Clancy to the present day (although acknowledging the Trump Presidency is beyond them; if Armando Iannucci ain’t gonna do it, no one else should try), setting it in world of SIM cards, video game chat, drones, Ebola, and most importantly, Islam. They make a few moves against this being a story about white people waging war against brown people, largely through flashbacks and having Pierce be Muslim-by-conversion, but it’s quarter-hearted at best; every gesture they make is only a gesture, never part of the story. Non-domestic anti-terrorism stories are essentially imperialist: the plot is always “prevent people whom we’ve fucked from fucking us.” Most likely, the only ways to fix this are to give your story a historical scope or make the Muslims the protagonists, and neither will happen on a show called Jack Ryan. (The assault on a U. S. black site in the first episode, directed by Solute non-favorite Morten Tyldum, is moderately badass though.)

Expanding the time frame from the 2+ hours of a feature film to the 7-8 hours of a miniseries allows for a Clancian breadth of plot, with several strands set up in the first half that come together in the second,** and it allows for a lot of characters besides Ryan to take the stage. Even with all the settings, the story has good momentum; Amazon series largely avoid the bloat of Netflix and HBO series, but whether that’s a studio mandate or just dumb luck, I don’t know. Cuse and Roland also pay attention to procedural detail and meetings, but that makes the Jack Is Always Right plot stand out even more. (In that way, it’s a faithful adaptation.) If this gets a second season (this finale sets up Pierce and Krasinski to return), there’s a chance they’ll fix the problems and live up to the potential here, a story where Ryan has to choose between doing the job and his self-righteousness.

9/11 killed Clancy’s Jack Ryan. The films before then were progressively less faithful to Clancy’s books, and less good (that’s correlation, not causation), with the Ryans and the stories getting more generic. The 2010s Ryans have thrown out Clancy’s work entirely, and gone back to the beginning with the character, trying to set him in a much messier global order, and just maybe make him a messier character. For all my snark directed at Clancy here, there’s a specificity to his Ryan; Baldwin and Ford came the closest to getting that particular combination of nerdery and espionage that define him. Clancy’s Cold War vision, though, doesn’t generate compelling stories in this world anymore (it’s no accident that the big spy fiction in recent popular culture, The Americans, had to relocate itself into that earlier world) so throwing out the texts and most of the character was necessary. As actors, Pine and Krasinski point towards what Jack Ryan and espionage stories could be for our time, but their creators still have a long way to go.

*Of course, what we called “right-wing nutjob” then now receives full state funerals with lots of impressive speeches and full coverage on CNN.

**One such strand, involving a drone pilot, goes nowhere–unless Cuse and Roland wanted to film the first (very mild) cuck porn to appear under the Clancy name.