Leo Tolstoy’s 1877 Russian masterpiece Anna Karenina has been called — including by such luminaries as William Faulkner — “the greatest novel ever written.” Quite a legacy to live up to, especially if you’re trying to get this son of a bitch out of post-production in time for an L.A. Oscar-qualifying run, or you have to be done with the BBC’s sets by the time the next season of Blackadder is supposed to start filming.

Let’s back up. The trials and tribulations of Tolstoy’s Tsarist Russia have proved remarkably resilient to the shifting mores and cultural expectations of the past 140 years. Anna Karenina has transcended the medium of its genesis — it’s been adapted not just to the silver screen, but also to the opera house, the ballet floor, and the radio — as well as its language to become one of the most frequently adapted novels in history.

So what is Anna Karenina all about? To boil the story — 800+ pages — down to its simplest description, Russian socialite Anna Karenina (hey, that’s the name of the book!) jeopardizes her insulated world, and her marriage to government bureaucrat Alexei Karenin, by having an affair with dashing military officer Count Vronsky.

Okay, so basically you’ve got a love triangle, right? At least, that appears to be the cleanest way to turn 800 pages of Russian realist prose into a two-hour film.

Tolstoy famously began his novel by telling the reader that:

“Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.”

Perhaps the screen world’s Anna Karenina‘s follow the same principle. Perhaps every cinematic Anna, Vronsky, and Karenin is unhappy in their own unique way, different not just in performance and context, but visually; striking a different image of unhappiness for audiences in their own time and place.

Let us explore.

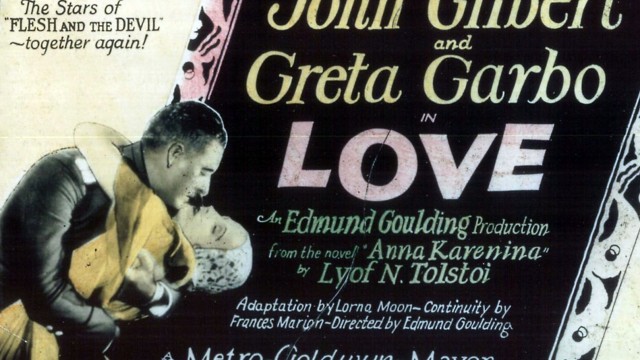

1. Love (1927)

Our first — though, admittedly, not the first — cinematic Anna Karenina throws us off by ditching the familiarity of Tolsoy’s name in favor of the minimalist title of Love. Interestingly, the title was originally supposed to be Heat, but if Michael Mann envisioned his ’95 crime epic as a take on the Russian novel, he apparently kept that to himself.

Anyways, MGM, the shiniest and glossiest of the Old Hollywood studios, and the most inclined to prestigious literary adaptations, got in on the Tolstoy game even if they didn’t want to get in on the Tolstoy name.

Anna, the wife and mother, got the privilege of being played, in one of her earliest American roles, by 22-year-old Swede superstar Greta Garbo. But top billing, surprisingly, went to John Gilbert, one of the biggest stars of his day, but now mostly forgotten. He was pretty much the embodiment of the silent matinee idol, but at 30, was already nearing the end of his career. By 40, he was dead.

As can be seen, this Anna is anachronistically dressed in 1920s fashions, with a smart bob haircut and sharp flapper’s cap, quite out-of-place for feudal Russia. She’s also younger than Gilbert’s Vronsky. This is important, so pay attention.

British thesp Brandon Hurst (age 61) played Karenin. He basically looks exactly what you’d expect a stiff, stuffy bureaucrat to look like. He appears to have never had a sexual thought in his life, and if he did, the sheer shock of its appearance must have caused that him to lose 75% of what I’m sure was a full and flowing mustache at some time.

In addition to the title change, American audiences were given a newly written “happy” ending, while the Europeans were forced to make due with the more downbeat Tolstoian ending. Poor them.

2. Anna Karenina (1935)

The transition from silents to sound in the 1920s and ’30s allowed for Hollywood studios like MGM to remake their pre-existing properties with the new techniques. So that’s just what they did. And they didn’t even have to ditch Garbo.

Whether or not Greta Garbo, at this point 29, was more appropriate or less appropriate for the part after nearly a decade of hijinks in the Hollywood hills, that’s up to you, but one thing that is objectively true is that her wardrobe was certainly more accurate.

Fredric March, a.k.a. handsome Valjean from a few days ago, was Vronsky. Looking more than a bit like John Gilbert, he’s still crucially a good eight years older than Garbo. (This is not supported by the text, by the way).

Karenin, on the other hand, was played by Basil Rathbone (age 43), who seems much more in the Gilbert-March mode than stuffy old Brandon Hurst. He’s not a hunky American like March, but simply by looking at him you can tell he’s got a dapper quality. Anyone who can go toe-to-toe with Errol Flynn in a sword fight could hardly be called stiff.

3. Anna Karenina (1948)

Vivien Leigh got in on the action when the Brits made their own version in 1948. One wonders if she had to ask for Garbo’s permission.

At 34, she was older than Garbo, and, as photographs like this one can attest, her Anna appears a bit more clenched or restrained than Garbo’s Anna. While Garbo’s golden locks peak out from her heavy dark clothing, perhaps signifying a kind of light peaking out from external repression, Leigh’s Anna appears entirely dressed and made up even while showing “more” of herself than Garbo.

Kieron Moore was her Vronsky. He’s clearly a younger man here, younger than previous Vronskys, and only 23 to Leigh’s 34. Nevertheless, the mustache was apparently non-negotiable.

British stage star Ralph Richardson (age 45) looked like a Russian caricature as husband Alexei Karenin. He even looks to have a little Lenin in him, which would be anathema to a Tsarist official, but would serve to make him particularly unlikable to the anticommunist audiences of 1948.

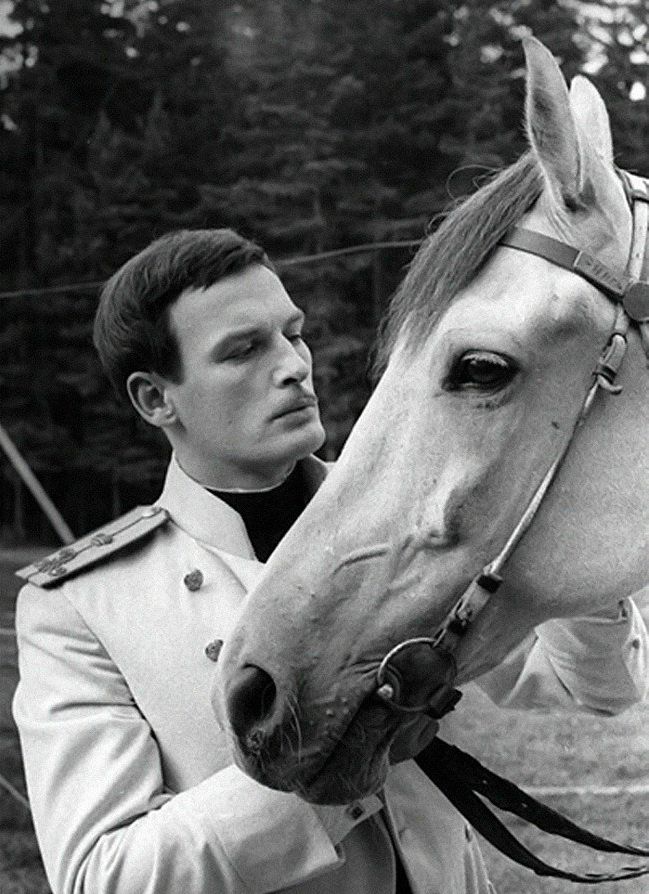

4. Anna Karenina (1967)

In 1967, the Soviets got in on the act, not wanting the Western capitalist pigs to have all the fun. Tatiana Samoilova — 33 year old Russian actress — was Anna IN GLORIOUS COLOR.

Well, the colors were mostly just black and white, but still. Something about the Russian setting seems to favor dark eyed women in white.

In one respect, Vasily Lanovoy was a rarity among Vronskys — at 33, he was exactly the same age as the actress playing Anna — but looked similar in most other ways. (Though his mustache does appear to be in retreat.)

Somewhat incredibly, Lanovoy was Samoilova’s ex-husband, which I’d imagine would add layers of internal conflict that are beyond my poor power to comprehend.

But for Anna Karenina the character, she had to make due with stuffy Nikolai Gritsenko — 55, but a hard 55, and every inch the stuffy old aristocrat, as her Karenin.

5. Anna Karenina (TV, 1977)

In 1977, British TV returned to the story for a 10-part series. What’s notable here? THE BLACK UNIFORM dammit. Nicola Pagett (32) was Anna, Stuart Wilson (30) was Vronsky, and Eric Porter (49) was Karenin.

A 1997 Warner Bros. version was the first American adaptation shot in Russia. 30-year-old French actress Sophie Marceau played Anna, while Sean Bean (age 37) got to play Vronsky, and presumably betray the Russians to the Orcs or something.

We’re back to the white uniform, but Vronsky is still older than Anna, a strapping man in his late 30s. The white-and-black contrast is apparent again, even in the age of color.

James Fox — age 57, but looking older — was Karenin, once again old and jowly and pear-shaped, very much in the Nikolai Gritsenko mode.

8. Anna Karenina (2012)

Which brings us to the most recent version, Joe Wright’s 2012 deliberately theatrical adaptation. Keira Knightley, of course, played Anna. At 26, she’s the youngest Anna since the first time Garbo played the role. Which, oddly enough, makes her the most accurate, at least by that criterion.

With her hair done up in doll-like curls, one might think of this Anna as being particularly coiled and clenched, but the dominating color on this Anna is a sharp and passionate red — seen here sticking out like the feather of a particularly resilient bird — around which director Wright based his color scheme.

Likewise Knight’s youthful Anna, Aaron Johnson, at only 21, made the youngest Vronsky. He kinda looks like a poodle, or, more charitably, a ballet star, and a far cry from alpha male types like Reeves or Bean. His golden curls mean he looks more like Greta Garbo’s Anna than any previous Vronsky, which I suppose is an accomplishment of sorts.

And finally, Jude Law (who at 38 honestly could have played Vronsky in most versions of this story) was cast strongly against type as the repressive and puritanical Karenin, his dashing good looks obscured — but not hidden — behind a beard, glasses, and receding hairline. In other words, this Karenin was a Vronsky lurking beneath the surface of the stiff bureaucrat, an Errol Flynn pretending to be a Ralph Richardson.

Conclusions:

Before we conclude, let’s take a moment and discuss age. Actors’ ages may be a shallow way of looking at film, but this series is about nothing if not the significance that can be found in being shallow.

Tolstoy’s Anna is a wife and a mother, but she is remarkably young by our modern standards. Context reveals that she is only about 26 or so, given that aristocratic Russian women married at around 18 then, and Anna and Karenin’s son is 8 at the end of the novel. Combine that with Anna being “nearly twenty years” younger than her husband, 46 at the end of the book, we can get a good idea of the central married couple and how it is they relate to each other.

The mean average age of these eight onscreen Annas is about 26, so fairly accurate, though that statistic is brought down quite a bit by Garbo’s first attempt at the role. For Alexei Karenins, it is 51, inching towards late middle age. The Vronskys are a mixed bag, from the college kid aged Aaron Johnson to someone like Fredric March, nearly twice that age.

So what can we deduce? That people tend to see this story as a simple love triangle between a beautiful woman, a handsome slightly older hunk, and her much much older, unattractive husband? Anna and Vronsky alike have been incarnated by good-looking movie stars while plain character actors are slotted in to be Alexei Karenin. Does the beauty of our cinematic Annas and Vronskys give us as an audience permission to ignore their adultery? Do we have less sympathy for a cuckold if he’s a bitter old man offset by beautiful younger folk?

I am not certain, but each film and television retelling of Anna Karenina finds its own reasons for the conflict: maybe it’s sex, maybe it’s passions of another kind, maybe it’s a simple matter of age difference. Is Anna a young woman who undergoes an initiation into the ugly world of adult emotions? Is she an older mother who regains the spark of youth? Each individual who adapts this story seems to have their own answer to this question, and perhaps you do too.

So long as new answers can be given for these old questions, I’d expect we haven’t seen the last of our little Russian love triangle. So don’t put those white officer’s jackets into mothballs just yet.