Try not to write when you’re living here!

-Rosemary Howard (Carrie Fisher), 30 Rock

As our Professor of Shield Studies has written, drama is a subtractive genre. Everything that isn’t an action by the characters reduces our identification with the characters. To maintain this kind of focus, though, a story must often sacrifice detail. The Shield held to this so well; we rarely see the details of our characters’ lives, and we certainly don’t learn anything about their, well, character through them. We learn through their actions.

The Shield treats its setting in the same way. The show uses 21st-century Los Angeles effectively, but it never feels like it needs to explore the details of the city beyond what comes into contact with the Barn. While the details of The Shield’s Los Angeles resemble the real-world L.A. (and in a way many shows don’t, focusing on the gritty underbelly), what’s important to the story is that the Farmington District in L.A. is the territory the Strike Team governs, one with many conflicting and competing interests jockeying for power, which they have to manage. To that end, The Shield isn’t neglectful of Los Angeles as a setting, but it’s also not “world-building” its own Los Angeles. The setting’s details draw on the Los Angeles we already know, as opposed to creating a world where learning the details is important to understanding the story. (David Simon’s Baltimore might serve as a contrasting example.)

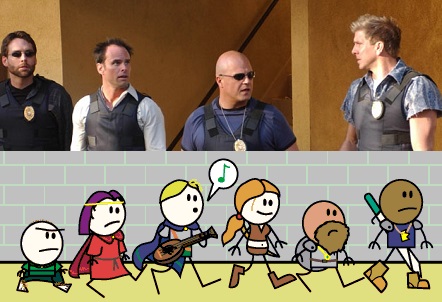

I think of this in conjunction with my favorite long-form webcomic, The Order of the Stick, which I find has a surprising number of similarities with The Shield despite being a fantasy-based tale of comic heroism and not a police-based tragedy. Set in a self-aware, fourth-wall-breaking stick-figure world that runs roughly on the Dungeons & Dragons 3.5 ruleset, OOTS has a similar relationship to its setting, although the construction of that setting and relationship is quite different. The Shield draws from the real world of contemporary Los Angeles to create a setting for its classical questions; Order of the Stick, drawing from D&D rules and fantasy stereotypes, cannot draw from any specific place, and in fact tends to lean into this aspect by purposely giving locations generic names. (Creator Rich Burlew has said that he by and large purposely avoids giving details unless they’re needed for the story; among other things, he doesn’t want to contradict himself, something the rules-obsessed part of the fanbase would be quick to notice.) The names are so generic they’re often part of the comedy: A forest named the Wooden Forest. Characters mentioned on a list but never appearing in the strip who are named Notseenicus and Offpanelio. Passageways through mountain ranges named Fissure Gap and Passage Pass. An Abbott and Costello routine leads main character Roy to be mistaken for the King of Nowhere– a real kingdom in OOTS, mind you, and a country distinct from the countries of Somewhere, Anywhere, and Someplace Else. (Roy could never be mistaken for the King of Someplace Else; it’s a democracy.)

By not developing the world more than necessary, however, Burlew avoids one dilemma of certain genre stories and literary-minded works: Running the risk of letting the world overshadow the characters. The Shield could have, like so many Prestige TV Shows, taken episodes to make day-in-the-life stories of lesser-seen characters in the Barn or on the streets, but it chose not to. The forward thrust of the story was more important. Burlew has the opposite problem: With such a generic backdrop, there are few if any side roads to be taken in the main story. All roads ultimately lead to the main plot in one form or another because of the lack of detail. Thus, the main characters– both heroes and villains– remain the focus, and insofar as we meet side characters, it’s in proportion to their importance to the main plot. (That said, Burlew has written some prequels and side-quels for OOTS, but they are separate, self-contained works from the main series.) Having said all that, Burlew has an eye for picking which details of personality, character, and setting are necessary to the story, and so the story never feels generic. The characters are written with both the sense of personality to make for an effective comedy (very many strips end in a punchline) and the sense of character to make for an effective drama.

I often compare The Order of the Stick to A Song of Ice and Fire, in part because they are both attempting long-form fantasy works (seven books apiece, even) but also because they are so wildly different. Martin has had the opposite problem: With a world rich in history, detail, and population (make no mistake, the scope of Martin’s imagination for the setting of Westeros and related lands is nothing short of stunning), Martin, beginning with fourth book A Feast For Crows, often found himself telling side stories or introducing new characters, exploring the setting, rather than continuing to drive the main plot forward. Indeed, even now Martin seems more interested in working on prequels and spinoff stories from the ASOIAF universe with HBO than with finishing the main story.

Perhaps this is because Martin doesn’t know how to get the story to go where he wants it to (he had a strong act one and seems to know what he wants act three to be, but act two has been a struggle for him to write). Perhaps it’s because he’s more interested in the world of ASOIAF than in the plot. The latter is not an option for Burlew; as for the former, the story has become better-paced and -written the longer it has gone on, rather than going slack, and Burlew said he has an outline of the entire plot and that it will run seven books, no more, no less. (As of this writing, the series is well into, and presumably nearing the end of, book six.)

Drama takes discipline, and in the case of both The Shield and The Order of the Stick, sometimes the discipline is to not give into the temptation of world-building and instead keep the focus on the characters and their actions.