New Years From the Brink

Nostalgia is a curious thing. The idea of the past being a simpler, easier time has always struck me as the rose-tinted spectacles of a conservative ideology: if it was great for me, it was great for everyone else (or if it wasn’t, the ‘others’ knew their place). So, what about depictions of the past in general? The past can be rich treasure trove for artistic commentary on the present. It can be idealistic; the imagination of art from a different era to frame contemporary topics and ideas. It can be realistic; capturing the warts and all depiction of history to illustrate what areas have changed (or not) over time, for better or worse. Every once in a great while an artistic work will manage to be both; frankly depicting a less than flattering portrait of the past, while still acknowledging its creative peaks. The Clash: New Year’s Day ’77, a recent BBC 4 documentary by Julien Temple, is one such work.

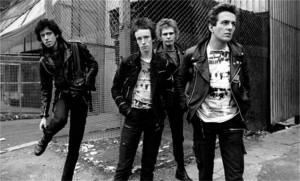

For those unfamiliar with Mr. Temple’s filmography (you poor souls), he is best remembered for collaborations with the Sex Pistols, including the documentary, The Filth and The Fury, and the mockumentary, The Great Rock ‘n’ Roll Swindle (which, according to James Nice’s Shadowplayers: The Rise and Fall of Factory Records, was shown at Ian Curtis’ wake). Temple is both an established documentarian in addition to being an acclaimed music video director in his own right; he understands the needed vibrancy to make the history of music more than the visual equivalent of a greatest hits montage. Temple has always had an innate understanding of how social trends inform musical tastes. This undoubtedly will come as a surprise to few, but given how so many music documentaries follow a tight focus on the band itself (which can be compelling and moving in its own right), there is a special joy at the documentaries that step back and look at the wider ‘push-pull’ relationship between society and a particular music movement, as seen through one band. In the case of The Clash: New Year’s Day ’77, Temple illustrates the political disillusionment via the rise of a band that would symbolize punk in all of its messy, furious glory.

The documentary begins with a dedication to Joe Strummer (RIP), followed by a female presenter (whose name unfortunately escapes me), saying it will soon be 1977, the year of Queen Elizabeth II’s Silver Jubilee.The documentary then launches into a collection of newscasters taking celebratory drinks, snippets from a news report interviewing people with the UK’s most common surname (Smith) about their hopes and fears for 1977, along with footage of raucous New Years celebrations in Britain throughout the years. As the documentary progresses, viewers are treated to never-before-seen (more on that in a bit) footage of The Clash during their rehearsals, leading up to footage of their first concert at the Roxy on New Years Day of 1977. The interviews with the bands, coupled with the grainy footage of them performing hasn’t lost any piquancy in the nearly 40 years since it was recorded. Temple balances the band footage with clips and interviews showing the myriad problems of late 70s. Temple doesn’t shy away from showing the hardships of the time; the footage of the 1976 Notting Hill riots are one such example. However, he brings a subversively idealistic lens to the material. One watching the documentary wouldn’t get the impression of the work being celebratory in its depiction of poverty. Temple argues that while Britain was indeed in the dumps (urban decay, unemployment, the garbage strike, among many other problems), there was rightful anger, as exemplified by the punk scene, and an honesty in admitted the fucked up state of the nation.

Beyond being a feast for music lovers and fans of The Clash, The Clash: New Year’s Day works as a fascinating historical artifact (perfect for anyone with an interest in history or sociology/anthropology). Temple shows how the renewed growth in the 60s gave way to urban decay in the 80s before gradual gentrification unfolded in the coming decades. In an interview with BBC, he remarks, ‘A lot of the material we acquired from the BBC and ITN seems like it’s from another world. Some of it is so twee and old-fashioned it feels like it’s the 1950s rather than the 1970s. But it was important to have that stuff alongside the gig and the interviews: Clash fans are going to love the film but I wanted to grab other people too.’ One of the documentary’s most striking moments, Temple shows how the fruit and veg market in Coven Garden (beautifully captured in Alfred Hitchcock’s underrated masterpiece, Frenzy), right near the Royal Opera House, faded into near emptiness only to be reclaimed by wealthy yuppie types. One can see the beginning of the ‘social mobility’ ideology that would be a cornerstone of Thatcherism (even if in reality few benefitted from it).

According to a BBC interview with Mr. Temple, The Clash: New Years, the documentary first began as a student film in 1976 and ’77. When asked about whether the documentary was an exercise in nostalgia, he states, ‘Quite the opposite: I think it’s about the future, not the past. Punk is in some ways a challenge still to be met. I think the energy of Punk is really needed now, though it’ll have to raise its head in other ways.’

In many ways, the timing couldn’t have been better for this documentary. 2015 is the year of Britain’s general election, and will an important tipping point in seeing where the nation goes. Change will be necessary, but how change will manifest itself remains to be seen.

Embedded below is the documentary in its entirety. Enjoy it while it lasts!