David Mamet’s Spartan was released five months before Michael Mann’s Collateral and they have a lot in common: each a tight, well-constructed, straightforward genre picture that might well be the best thing the director ever did. (For Mann, the only other competitor is Heat; for Mamet, it’s Homicide.) Neither Spartan’s story nor its structure has anything new to offer; it’s a quest picture, with Val Kilmer’s Bobby Scott trying to find and rescue the President’s daughter, and (surprise!) Things Are Not As They Seem. What makes Spartan great, what makes it fuckin’ Mamet, it how it’s done: compressed beyond lean into something almost abstract, a pure structure of language, action, and language-as-action. Apart from perhaps The Driver and Le Samouraï, there is nothing like it, not even among Mamet’s own works.

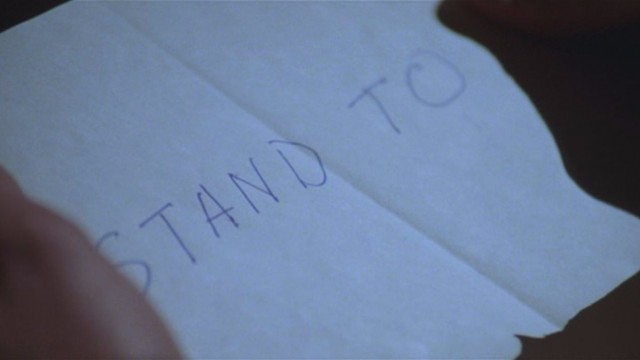

The film opens with an eight-minute training sequence at “Cadre,” where we meet Scott, trainee Curtis (Derek Luke), officer Jackie Black (Tia Texada, who looks like a non-glam Angelina Jolie and deserves to be a bigger star). These scenes aren’t plot, but a statement of method, like a composer giving us a first movement of chords before the piece gets launched. (Steve Reich’s Music for 18 Musicians is the example here.) Scott tells Black “don’t you teach ‘em knife fighting. You teach ‘em to kill. That way, they meet some sonofabitch studied knife fighting, they send his soul to hell.” Lionel Mark Smith begins the final test by telling Curtis and another trainee “on my signal, you will execute, nothing more, nothing less.” As Scott leaves, he receives the message STAND TO, and now Spartan executes, nothing more, nothing less.

Mamet has always proclaimed the Aristotlean necessity of reducing drama to action: “if the place of action is not germane to the plot (i.e. The Room in Which My Sister Secreted My Share of the Inheritance), leave it out, you writers. . . .Why? Because then we’ll watch the Action.” (No surprise that Shawn Ryan was a big fan, nor is it a surprise that Mamet directed an episode of The Shield around this time with much of the supporting cast of Spartan, nor that he and Ryan collaborated on the TV series The Unit afterwards.) He reduces the drama even farther here, dropping all exposition, and burning every line down to the fewest, most rhythmic words. Every line becomes its own action. From the beginning of his writing career, Mamet has insisted on words as actions: “In the narration or recapitulation of serious matters our peers were never said to have ‘said’ things, but to have ‘gone’ things; we ten- and twelve-year-olds thereby recognizing a statement as an action.” (This is from one of his earliest essays, “Capture-the-Flag, Monotheism, and the Techniques of Arbitration.” In addition to that fucking well awesome title, it’s also essential for understanding Mamet’s work.) He has never realized as completely or as effectively as in Spartan.

INCOMING: SPOILERS

At no point do we hear “Major Scott, I’m glad to see you’re back from the training mission. As you know, I’m head of the Secret Service detail that covers the President’s daughter. She has apparently gone missing and we need to find her, quickly. Can you help us?” What we get instead is a single line, repeated so many times and with such variation it becomes the purest music, the “fine art of repetition”: “where is the girl?” (We never hear “President” or “President’s daughter” at all, and only rarely do we hear her name, Laura Newton.) Outside of Kilmer, Luke, and Kristin Bell as Laura, all of the actors here are Mamet family members and veterans–Smith, Ed O’Neill, William H. Macy, Clark Gregg, Vincent Gustaferro–and they know exactly how to say this language. Gustaferro gets my favorite variation, spoken with just a touch of Chicago accent to a Secret Service agent who fucked up: “where is the girl? Where is your principal?” Even a variation like “where’s the girl?” (Ed O’Neill’s entrance line) has impact: three syllables instead four make the line sound unbalanced. Although O’Neill’s voice doesn’t go up on “girl,” it comes across as a question. The structure of the story reinforces one of Mamet’s principles of acting: don’t emote, just say the words. I’m not sure that can work in all drama, but it absolutely works here. Emotion doesn’t matter because there is no time for it. There’s only the action, and words are actions.

He compresses things even further in the first forty minutes, right down to the language itself. Almost every line is in monosyllables, or with only a single polysyllable. Almost every line is equally stressed; Aristotle notes that “conversational speech runs into iambic lines more frequently

than into any other kind of verse,” and shifting to monosyllables comes off as alien at first. The lines have the cadence of gunfire, especially trained gunfire: bang. bang. bang. bang. These words are all commands, spoken either between people in a working community who will immediately take action on them, or people who are not in that community who will either take action on them or get killed.

It’s the equivalent in dialogue of what Frank Miller did in images in Sin City (the last thing he wrote before his mind went), partially drawing the images to make something starker and sharper than reality. Sometimes it’s nearly a literal equivalent, as Mamet often drops words that would be normally used in conversation to create stronger, more angular rhythms of speech–there’s a “who” missing in Scott’s line to Black above. It’s not realistic, it’s essential, and it has such purity you can get a contact high just from hearing it:

–Your man says he was on post until he turned her over to the night watch.

–Were you fucking her. We’re gonna find out.

–I’ve got two days to run in before the press wakes up.

–You’re entitled to shit. You’re entitled to Tell Me What You Know.

–Get me there. Get it on the net. Everyone off. Call everyone off. Just me. Just me and him. (pause) Indicate you heard me.

–Now here’s the cut-off point. Here it is.

Look at, or better yet, listen to this next scene closely, with Scott and Curtis interrogating Jerry, the pimp, in an alley. Scott responds to Jerry’s “I think you broke my arm” by slamming it into a dumpster and saying “now it’s broken,” a direct and brutal ownage. Mamet doesn’t linger on the broken arm, because what matters is not the pain but that we learn how far Scott can go, and how quickly. Jerry learns that too:

–Where is the girl, Jerry? Where did you take her? Where did you take (shows picture) this girl, Jerry?

–Where did you take this girl, Jerry? (to Curtis) Take your knife out.

–Where did you take the girl, Jerry? Take his eye out. (Curtis looks at him)

–You bet your life.

There are maybe a thousand ways to write those three lines to Curtis, and none of them are as good. (Note, by the way, the subtle variations and repetitions in the lines to Jerry.) All three lines to Curtis are four equally stressed syllables, and Kilmer delivers all of them identically. All four of them are actions, specifically commands. After each line, Mamet cuts to Curtis, then back to Kilmer; that gives Curtis’ look an action as well. By looking at Scott (and Mamet showing him looking at Scott), he’s effectively saying “confirm the order, sir” and “You bet your life” means “confirmed.” Most writers would come up with something like “just fuckin’ do it!” because most writers wouldn’t get what’s happening or hear the music in that scene, and imagine that tossing in “fuckin’” equates with being a Tough Guy. (Mamet’s use of obscenity is as precise as everything else in Spartan; see below.) Even a different four syllables, like “do what I say!” doesn’t work: that line tries to convince, not confirm. There’s no conversing with these twelve syllables, let alone arguing with them; like so much in Spartan, we’ve seen this scene before, but here we see the most pitiless, essential version of it.

There are maybe a thousand ways to write those three lines to Curtis, and none of them are as good. (Note, by the way, the subtle variations and repetitions in the lines to Jerry.) All three lines to Curtis are four equally stressed syllables, and Kilmer delivers all of them identically. All four of them are actions, specifically commands. After each line, Mamet cuts to Curtis, then back to Kilmer; that gives Curtis’ look an action as well. By looking at Scott (and Mamet showing him looking at Scott), he’s effectively saying “confirm the order, sir” and “You bet your life” means “confirmed.” Most writers would come up with something like “just fuckin’ do it!” because most writers wouldn’t get what’s happening or hear the music in that scene, and imagine that tossing in “fuckin’” equates with being a Tough Guy. (Mamet’s use of obscenity is as precise as everything else in Spartan; see below.) Even a different four syllables, like “do what I say!” doesn’t work: that line tries to convince, not confirm. There’s no conversing with these twelve syllables, let alone arguing with them; like so much in Spartan, we’ve seen this scene before, but here we see the most pitiless, essential version of it.

Although it’s beyond the scope of this review, Spartan has a lot of nonverbal greatness and ownage too. Mamet’s skillz as a director have only grown since House of Games, and he accomplishes some great sequences without dialogue, like the chase of Jackie Black that opens the movie, or part of the con game (a staple of everything Mamet) that Scott and team run on Saïd Taghmaoui’s character. Scott has declared (again, one polysyllable only) “I am here to get the girl back, and there is nothing I will not do, to get the girl back” but Mamet and Kilmer give us a long, silent moment where we see how Scott has to psych himself up to shoot a handcuffed man dead. Mamet continues to use objects or images as clues (here it’s the (-% emoticon and an earring) and has a purely cinematic moment where a close-up on a photograph turns the plot. Mark Isham creates a haunting and never overbearing score that incorporates a Polish folk theme, and Juan Ruiz Anchia (another longtime Mamet collaborator) shoots it like a modern noir, very close to Newton Thomas Sigel’s work in The Usual Suspects.

Until Curtis exits the film in a moment that’s both foreordained by the plot and shocking in its direction, he and Scott have a professional relationship of apprentice and master. Mamet has given us so many great stories and dialogues of men fighting each other that this one comes as a special pleasure. It isn’t “camaraderie” (as Scott sez, if he wanted that he’d join the Masons) but the mutual respect of people bound by a common goal. (Curtis carries a pamphlet from his grandfather, “Rules of War,” that includes “don’t you ever lie to another Ranger.”) It’s the kind of relationship that allows for criticism, advice, or reflection because all of those things are acts of respect and therefore community. In addition to dialogue and plotting, we get to see some of the details of professionalism, as strong here as in Mann’s films: when Curtis sets up his sniper’s position outside a beach house, at no point does he set down his rifle or take his eyes off the house; and when he’s sighting, he will not let the scope’s crosshairs rest on Scott.

In Spartan’s second act, professionalism itself gets called into question, and therefore so will language. After the daughter and her professor turn up drowned, Curtis tracks down Scott because he doesn’t believe it. (“I saw the sign” becomes as dominant now as “where is the girl?” earlier.) Bracketing the STAND TO at the beginning, Scott tells Curtis “stand down” and gives him the professional warrior’s code, again in the short, monosyllabic sentences of the first act:

–You got to set your motherfucker to Receive. Listen to me. They don’t go through the door. We don’t ask why. That’s not a cost. It’s benefit.

Mamet has written “film is a hierarchy and it was my job to do one part of it,” and that’s as good a description of Scott’s code as you can ask. When Curtis produces Laura’s earring from the beach house she was never supposed to be at, Scott’s world begins to change, and the story turns. (In a film that’s so verbal, Mamet carefully shifts the plot on physical objects: the earring, the second hole in the photograph, a strip of photographs. Whatever happens with language, things cannot be denied here.)

After Curtis gets killed, Scott briefly considers running (“you gotta get me to the tall corn”) but decides instead to go see the President’s wife, currently in rehab. He runs into Linda Kimbrough as a Secret Service agent, who confronts him with what really happened: “they snatched her while he was cheating on his wife. It comes out, they lose the election.” So, the cover story goes out that she drowned, “so he’d stop looking,” and even the President has been conned. Mamet is so viciously incisive here and Kimbrough makes every word land. This spins an earlier scene where a member of the rescue team watched a news report with Scott and told him that the daughter and the professor were found naked and loaded with cocaine; now we know that scene was a con on top of another con. (Later, we’ll find that’s where Scott’s knife got a tracker planted in it.) And I’ve never heard the weakness of the media explained so concisely as this exchange:

–. . . .I know they lied. How do you fake the DNA?

–You don’t fake the DNA, you issue a press release.

Scott is literally up against the wall in this conversation, kept in shadow, and Kimbrough uses the same monosyllabic cadences as Scott does; this is the scene with Jerry again, except Scott is in Jerry’s role (and Jerry’s lighting), the man pinned down with all options cut off:

–Wait. Who will get her back?

–What?

–Who will get her back?

–I did my part.

–What part was that?

–They gotta get her back.

–There is no “they.” You are “they.”

Scott discovers (in the words of “Capture-the-Flag. . .”): “it was possible to swear falsely, and that there was, finally, no magic force of words capable of assuring the truth in oneself or in others,” that words do not have to be bound to actions. He discovers that the “they” who “don’t go through the door” have lied to him, that those above him in the hierarchy are not doing their job, that they are using him for a completely different job. That sets up one of Mamet’s most stunning scenes, and it’s all about the language. We go in the next scene to Scott in a booth at a bar, and his monologue here (the listener isn’t revealed at first) has all the force of a noble Shakespeare character suddenly speaking in prose rather than iambic pentameter; think of King Harry going undercover to talk to the soldiers in Henry 5: “I think the King is but a man, as I am.” Scott isn’t a warrior anymore, he is but a man, undone from everything he knows, and the monosyllabic rhythms by which he lived:

–It’s been quite a long while since my last confession. We were getting shelled in the open and I confessed I was frightened. So I suppose–I suppose I’m frightened now. There was a King, and he had a daughter, and she was abducted. He vowed to protect her, you see, but while he was indulging himself, shamefully, she was abducted. They tried to get her back and failed. Now his advisers realized that, if the girl returned, it would reveal the King’s shame to the Country, so they told him that she was dead.

Everything about this–the doubling on “I suppose,” a mark of fear, something we haven’t heard Scott do in the entire film; the long sentences; the polysyllables–reinforces Mamet’s approach to acting of enunciating over emoting. There’s no need to show emotion here, the words and their cadence do everything. (Note that last monosyllabic phrase to drive home the final meaning; Garry Wills has noted that Lincoln often used this technique.) Then the camera dollies back and reveals Jackie Black as the listener, and not just her words but her cadence pull Scott back to who he truly, essentially is:

–Ain’t nobody here but two people in green.

–It goes beyond that.

–Nothing goes beyond that.

That turns the story into the third act, which, sadly, is where the conventional nature of Spartan catches up to it. It’s exciting but mechanical and predictable, without the thrill of the earlier language. Scott’s real story ends as he launches the rescue of Laura Newton and there aren’t any more character beats to play out, only a final betrayal by the only one left in the cast who could do it. (Heist had this problem too.) We do finally get to see Kristin Bell as Laura, and she has the same intensity she brought to The Shield, someone who has never been a daughter to her parents, only a political asset. Scott rescues her, Jackie Black dies, he goes into exile, and the last scene comes back strong: in London, Scott catches on television another con game, another cover story that will allow the President to continue as before and will replace everything we’ve seen in official memory. Fittingly, Ed O’Neill gets nearly the final lines, words loaded with polysyllables, without force, the puréed speech of politicians that doesn’t mean anything, that just signifies caring and morality without implying–without demanding–any action. There’s not even betrayal in these words, because there never could be any promise. If the speech of the first act is pure ownage, this is the cadence of pure corruption:

–Terror takes many forms. I can conceive of no act of terror greater than the unforgivable, the ultimate destruction, that of the innocent. The kidnapping of Laura Newton has revealed to us, has allowed us to confront and will allow us to eradicate the international traffic in souls. It was brought about because of the love of a family for their daughter, a simple American act, the love of Americans for all our daughters. . .

Mamet doesn’t treat the structures of genre as obligation, but rather opportunity to refine his own work to its most potent form. (Of his ability to write dialogue, he has called it “a talent and not really very much of an exertion.”) When he adapted Terrence Rattigan’s The Winslow Boy, he wrote “it is, I think, a derogation to speak of Rattigan’s ‘craftsmanship,’ as it would be to say to Picasso, ‘Wonderful use of blue.’” So, without intending any derogation: in Spartan, Mamet used genre to achieve some of his best and purest writing and created one of the (in both senses) essential works of ownage of our time.