This is where it all begins, the first year of eligible films for the newly-created Oscar category of “Best Song.” I’m glad we didn’t start the series here, though, because this is a depressing slate of songs to write about, nothing worthwhile enough to feign enthusiasm over, nothing catastrophic enough to take any joy from picking apart. As if to set the tone for the category, the first contenders for Best Song are all mediocrities that reflect the most middlebrow tastes of the era.

What it reflects is more worth talking about than the songs themselves. Two of the three nominees are effectively a minute of song followed by ten minutes of that theme repeated by orchestra, because they were designed as vehicles for endless dance sequences, sometimes ten, fifteen, twenty minutes long: it was the age of the dance marathon, of dance-as-endurance-test. The lyrics are usually nothing more than the name and a brief description of the dance you’re about to watch, each one chasing to be the next Charleston, the next Rumba. You bring out Fred, write a few words over an earworm, and then have him and a series of other dancers do their thing over that earworm, over and over and over again. The music itself begins to grate, but we’re not there for the music, we’re there for the dancing, and that should tell you something about where the category’s head is during these first few years.

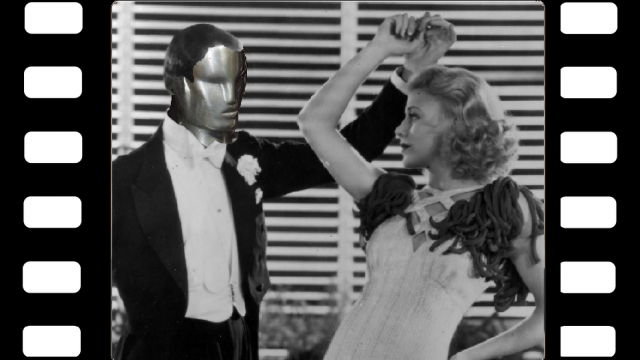

So that leads to our first winner, “The Continental,” from the The Gay Divorcee. After some stiff banter (it’s very “live theater, waiting for their cues”), an otherwise delightful Ginger picks up the main theme, composed by Con Conrad, and sings the introductory version. Now the main event begins, with Fred and Ginger doing their thing, followed by a whole ballroom full of dancers. But perhaps you’ve forgotten the name of the song, so just before the 9:00 mark, we bring out Oklahoma-born actor Erik Rhodes playing an Italian stereotype (and fake-playing the accordion) for another round of lyrics, followed by another round of dancing. Perhaps you want to know more information? Good news! Lillian Miles will come out around 11:30 to give us what sounds like a rejected B-side version of the song, followed by yet another round of dancing. After fifteen minutes I’m begging for the quiet release of death.

Maybe it sounds churlish to complain about what is, in effect, a standard format of the genre: after all, you could reuse my paragraph above for any number of musical and movie scenes that year, with only the names and timestamps adjusted. It’s also true that the dancing is frequently stunning, sometimes at the individual level (just wait ‘til we get to the Nicholas Brothers!) and sometimes as pure spectacle (like the next year’s winner, a classic Busby Berkeley production), but it’s also hard to overstate how disposable the music usually is.

To be fair, “The Continental” isn’t the worst of the bunch, just… not particular interesting, either. The lyrics are somewhat witty, at least. Herb Magidson was a busy but minor lyricist during the 1930s, and he gives “The Continental” a description that’s tongue-in-cheek (and sometimes literal tongue: it’s a song about dancing close enough to swap saliva with your partner), a dance craze that’s apparently swept across Europe even if its contours as an actual dance are a bit fuzzy. Ultimately, “it’s very subtle” because “it does what you want it to do.” Cute.

At least it has something going for it. It’s harder to be complimentary towards the other big dance nominee in this category, “Carioca,” from Flying Down to Rio. Vincent Youmans’ music is generically “exotic” (the wiki helpfully describes it as “a mixture of samba, maxixe, foxtrot and rhumba,” which is another way of saying it’s both everything and nothing), and I have a hard time believing it took two lyricists to come up with stuff like

Say, have you seen a “Carioca”?

It’s not a foxtrot or a polka.

and

It’s got a meter that is tricky,

A bit of wicked wacky-wicky.

Naturally it was a huge hit. It’s mostly remembered today as the first-ever pairing of Fred & Ginger, but what’s more interesting to contemporary eyes is the interracial trio of singers who trade off the lyrics at various points in the song. Unlike “The Continental,” this showpiece begins with an instrumental tune and a few minutes of Fred & Ginger before bothering to care about the words. Eventually, the first set of lyrics is performed by Mexican-American actress Motiva Castaneda (the future Mrs. Marlon Brando, who was only ten years old when Rio was filming) and by emphatically non-Latina actress Alice Gentle in brownface, followed by the first set of group dances; the next set of lyrics comes a few minutes later, performed by Etta Moten, and capped by a second Fred & Ginger bit. Castaneda is probably the most successful of the three, but the bar is low. Moten would go on to be a major cultural figure, but in her brief career in Hollywood, this was the only of her six or seven movie appearances in which she was credited at all (and even here, as “colored singer”). She is luminous here, but the style is all wrong, too operatic and formal for something this disposable. (This video below is the Moten segment; if you want to watch the segment with brownface, it’s here.)

We’ll have plenty of opportunity to talk about the icky politics of music and dance in early Hollywood; here it’s worth remembering that many of the era’s dance “fads” were outright thefts from Harlem dancehalls and Latin American “imports”, and most of the time these origins are erased or indulged for their exoticism. “Carioca” is especially interesting as a kind of case study of the latter: we have a fairly elaborate dance number with “ethnic” performers, until Fred and Ginger get a whole spinning stage (made out of seven linked pianos!) to themselves. Their footwork is technically brilliant, and the scene made them big stars, but are they the ones you’re watching? Even here, on their own territory (a Hollywood soundstage, I mean), they feel like Puritan colonizers.

For all this, you’d think I’d be relieved that the third and final nominee this year was not tied to a half-hour dance sequence, but the drippy love song “Love in Bloom” (by Ralph Rainger and Leo Robin) tests my patience even for short ballads. Here we have early Bing Crosby making doe-eyes at Kitty Carlisle until interrupted by her father (dean of the school where Crosby’s character is studying). The clip below has both the first iteration of the song and the later climactic version sung over the phone (!), which, to be fair, is harmonized nicely. In between we get an “improvised” comic riff on “Straight from the Shoulder (Right from the Heart)” that makes me wish Carlisle had stayed in the industry longer: her facial reactions are superb.

There’s not much to discuss about the song’s basic shape, which simply fills out the textbook-standard I-IV-V-I progression with the most obvious passing harmonies. Its piano accompaniment is strikingly reminiscent of one of the worst songs ever written, from the opening climb followed by descending dotted quarter + eighth notes to the overall harmonic “shape” of the phrase. It’s drowning in sap. Thank god for Jack Benny, who adopted “Love in Bloom” as his theme song and persistently played it out of tune, the only thing that served to improve it. With a slate like this, we’re lucky Best Original Song category lasted longer than a year.

What else could have been nominated?

As we discussed in an earlier installment, it’s hard to tackle this question before 1942, when the “Original” qualifier was added: anything, in theory, could be nominated, though it was rare for very well-known pieces to make it into the lineup. That said, a lot of the films of 1934 were adaptations of stage musicals and operettas, which opens up a giant field of possible contenders, not to mention songs where I couldn’t quite pin down whether they were original to the films or not. The latter category includes one of Josephine Baker’s greatest hits, effectively the theme song of Zouzou, “C’est lui.” The song appears a number of times in the film, but is fully unleashed in the movie’s climax, with Baker’s laundress character finally achieving her high elegance dream, anticipating Marilyn in “Diamonds are a Girl’s Best Friend” by two decades. Georges Van Parys’ music is a mildly jazzy take on the French chanson, and Roger Bernstein’s lyrics are witty and suggestive (Her lover chases after all kinds of girls: “His eyes undress them, / And sometimes his hands, too.”) Though less visually iconic than her operatic birdcage bit for the song “Haiti,” “C’est lui” is a definite crowd-pleaser and would become a staple of her live repertoire.

So help me, after all my whinging about the brief song + endless dance format above, my own pick for the best song of the year probably would have gone to one of them, albeit a real standout of the format. Composer Harry Warren, soon to be a titan of the Best Song category (11 nominations, 3 wins) and lyricist Al Dubin put together one of these throwaway songs for the year’s big Busby Berkeley spectacle, Dames, a little ditty called “I Only Have Eyes for You.” It’s great: the first phrase, when the singer is expressing his confusion, is built over a murmuring supertonic (ii) theme that naturally leads us to the dominant (V) just in time for the word “only” to break through over the major tonic key, like a ray of sunshine cutting through the fog. At the end of the phrase, a downward-drifting chromatic bass brings us back to the supertonic for another round, and Warren keeps things interesting with jazzy substitutions and a nicely cool, woodwind-heavy instrumentation. (The clip below is the song’s first iteration, before the giant dance number slash dream sequence. You should also check out Burgundy Suit’s in-depth look at Dames here.)

Other options included the Rodgers and Hart classic “The Bad in Every Man” from Manhattan Melodrama … or at least, it would become a classic after the lyrics were rewritten and it was re-released as “Blue Moon” (see Persia’s article here). Another extremely popular song that debuted in 1934 was Richard Whiting and Sidney Clare’s “On the Good Ship Lollipop,” sung by Shirley Temple in Bright Eyes. Temple was in like a dozen films in 1934 and sang in most of them, but I can’t bring myself to go through them all. Instead, I’m ending on this unrelated song from Murder at the Vanities and with no comment. Enjoy!

Previous installments: 1936, 1954, 1966, 1974, 1982

Next month: A (dare I say it!) really solid year for the category?