Interlude

Warning: Like all Conversations in this series, this contains SPOILERS.

wallflower: One of the distinct pleasures of world-building (as opposed to storytelling) fiction is all the small details and characters. From the first volume, Snyder made clear that he was creating an alternate version of American and even world history, and that will have lots of opportunities for stories and characters off of the main narrative. It almost feels traditional to have a volume like this, with one medium-length story (of course Travis comes back, he’s too awesome not to) and a bunch of extra-short stories. It’s a good structure; the shorter stories move forward through history from 1588 to 1940 and get bookends with some Skinner Sweet violence and splash pages. (The shorter stories also have a lot of guest writers and artists.) Thankfully, although there are connections to the larger narrative and characters, this doesn’t feel like filling in the gaps; the story that finished last volume is complete and satisfying. These stories feel like play, not in the sense of goofing off, but in the freedom of fiction, the way it lets you explore so many lives and styles.

As history, Team Snyder does something here along the lines of Cormac McCarthy–not just Blood Meridian, but everything that came after that, including No Country for Old Men, The Counselor, and The Road, where he wrote a disjointed but complete history of American southern border region as a history of violence and ownage. In McCarthy’s words, it wasn’t really about conquest but about violence as its own force with its own agency. Here, the bloodlust of the vampires takes a lot of forms but it’s always there, lurking in history, and it’s not always the most evil force around. You really see (and I do mean see) this in “Essence of Life,” where the greed and sexual sadism of Old Hollywood gives Hattie her bloodlust, really a thirst for revenge over blood. It does give more depth and pathos to her, but it also gives more play to the ideas of vampirism and evil that American Vampire has seen through all American history. In terms of plot, these stories are (I think) unnecessary; thematically, they’re essential. How do you see these stories as relating to the whole?

Avathoir: So I’m typing this Juuuuuust as I finished up reading the Anthology again, but for the most part I think they succeed in places where something like the Star Wars prequels fail: knowing what’s interesting and eschewing what’s boring or irrelevant. There is no “Darth Vader as a little kid” here that almost dragged The Beast in the Cave into being bad, everything here is interesting enough in its own right that it could be its own story, without sacrificing continuity points. We don’t NEED to know that the Native American child that the fur trapper saves is Travis’ ancestor, and we don’t need to know that Pearl’s great-grandmother had her own encounter with vampires before Pearl came along. But that’s the sort of thing that’s interesting regardless. The first one is what The Revenant should have been, the second one is From Dusk to Dawn with a feminist-centric plot.

You’re also right that this is a prime example of the history of American violence across all sorts of time and locations. Snyder was smart to have a bunch of varied people join this project rather than write all the stories himself. This is an anthology in every sense of the word, and a bunch of superstars in comics are working in a lot of different modes. I’d love to hear your thoughts on Simone and Lotay’s story filling out Hattie’s backstory even more (which you already indicated as an object of interest) and if any stood out for you. Even more so, were any of the stories duds?

wallflower: Probably “Bleeding Kansas” was the weakest, simply because it was too historically on-the-nose, the sort of thing Oliver Stone would do. American Vampire does its best work when it’s in the crevices of history, the less famous but not less important events and places. (Another advantage of the short-story format: the weak ones are over quickly.) I do want to give some praise to the artwork (by Ivo Milazzo) in this one, though, which is striking. A cliché that we often use for art is “painterly,” and Milazzo’s is more than that, it looks like watercolors, with the kind of shading that disregards the outlines and deliberately blurs details. It’s beautiful; more than that, it evokes the past without resorting to things like sepia tones and classical blocking. There’s still so much motion in these panels.

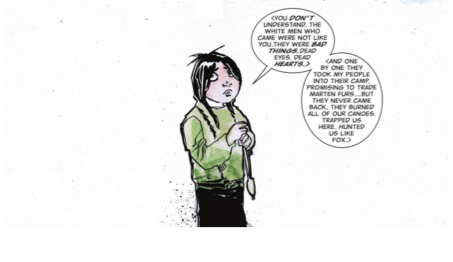

Also great and unique is Ray Fawkes’ work in “Canadian Vampire.” (So Travis Kidd is part Cree? Makes sense, actually; I think Elvis had some Cherokee ancestry.) This goes past comic-book art into comic-strip art, with a lot of  unfinished lines and negative space. Fawkes uses that to emphasize Kid’s youth and, well, smallness, and to give Jack Warnhammer an Old Testament prophet-type look. It also conveys well the sense of cold and space, and, again, it’s beautiful. It has much of the same feel as the first chapters of Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis–the world as it looks to a child. We haven’t seen any art like this in American Vampire, and these works alone justify the volume.

unfinished lines and negative space. Fawkes uses that to emphasize Kid’s youth and, well, smallness, and to give Jack Warnhammer an Old Testament prophet-type look. It also conveys well the sense of cold and space, and, again, it’s beautiful. It has much of the same feel as the first chapters of Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis–the world as it looks to a child. We haven’t seen any art like this in American Vampire, and these works alone justify the volume.

Gail Simone’s “Essence of Life” brings everything together–artwork, story, character, historical meaning. Creating a backstory to a mythic character is risky, because it changes the general to the particular. It works here, because we know this story, so painfully, is a general one–Hattie is just one of thousands of women who went to Hollywood to become famous and wound up with a producer shoving his dick in her mouth. It also works because the short-story format has some brutal economy; Hattie gets told in the second page “on your knees.” And then that’s followed with one of the best splash pages (Tula Lotay was the artist) in this entire Cycle.

That’s horrifying, and for one moment it feels like it justifies all the horror that Hattie will unleash. It throws forward nicely to another half-page image when she gets her revenge, which is as funny as this one is heartrending. (We won’t spoil it.) The way the boxes break up Hattie’s voice, the expression on her face like her brain just refuses to process this (Lotay gives her such varied and detailed expressions all through this story), the lines and blood-red of the image, the Gothic feel of it all–this is what David Fincher and Gillian Flynn were trying for in Gone Girl and never quite brought off, conveying (even if only for a moment) the sense of a violation so great that no violence can ever atone for it. That we know this was everyday life in Hollywood makes this so much worse. It reminds us that the Eurovamps Pearl first met and the producers of the preceding story (called, shockingly, “The Producers”) are different in means but not intent from those with power in our world. It does all this in eight pages; Fitzgerald couldn’t have done better.

Avathoir: Since you covered two of the ones I wanted to talk about so well already, I’m only going to add a little bit to them and then mention the one I like the most besides them. I love “Canadian Vampire”, even though it’s the briefest and in some ways the lightest of the stories we have on offer here, but Fawkes’ art, which you’ve already praised, is just incredible to me. He takes a color palette that shouldn’t work half as well as it does and makes it into something heart stoppingly beautiful, a stained glass world that seems warped and distorted but actually follows its own internal logic with perfect grace.

“Essence of Life” is for me the best story here, not only because Tula Lotay is an artist bar none (look at that splash page) but because Simone (whose Clean Room currently being published at Vertigo makes for an excellent expansion of some of the ideas and imagery present in this story) knows the right way to treat Hattie: she’s clearly sympathetic to her (and this poor, poor Hattie. I wanted to take her into my arms and hug her), while refusing to skirt around the fact that Hattie is still a sociopathic person. There’s no TRAGIC PAST here, just a simple acknowledgment of what leads a person to a particular place. Hattie knew what she was getting into yet she went and did it anyway. At the same time, that in no way justifies what happened to her, and the heartbreaking way she says “I didn’t cry.” as well as her meltdown during shooting is enough to convey such a different life that she could have lived. It’s almost enough to make you forgive her for what she did to Henry. Almost, anyway.

Simone’s dark humor is also wonderfully present here too, her depiction of Hollywood as full of pansexual degenerates is probably the most accurate depiction of industry power besides Barton Fink. The way it all shifts so easily from a dream into a nightmare and back (before going into a joke that Tarantino would be proud of) is wonderful.

Speaking of movies, I love Cloonan’s contribution here, which takes the infamous production of the legendary classic of silent cinema Greed and casts Skinner as Willem Dafoe in Shadow of the Vampire. It’s a great little bit of fun, and is a perfect example of history at the margins that this series is so good at exploring. If Skinner Forrest Gump-ed his way through classic cinema (just imagine him seducing away Faye Dunaway from Warren Beatty in Bonnie And Clyde) that would more than satisfy me.

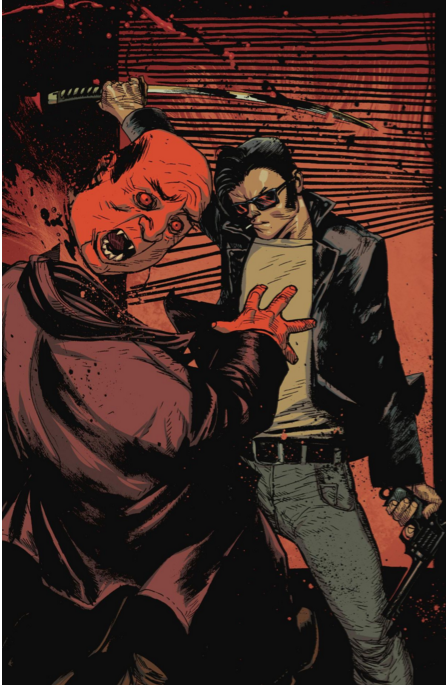

We’ve talked a lot about genre and cinema’s influence so far in America, which I feel is a really good segue into the one long story in this volume: The Long Road to Hell. It was actually published as a special rather than individual issues, and it’s without question the oddest story we’ve encountered in some ways. It feels like the first story set in the present rather than in the past, which I think is to its benefit. First of all, it has a timeless genre idea (the criminal lovers on the run), a great force of nature antagonist in Travis (who somehow has picked up a katana along his travels, and which he uses to great effect), and introduces the most genuinely odd character so far in Jasper, a young boy who is able to preternaturally sense a person’s inner qualities and whether or not they’re evil or good.

How did this story work for you? It’s so almost Tarantino-esque at parts it put me off a bit, but Snyder injects a lot of King inspired elements (the scene of Travis getting up and putting in his wooden teeth, Jasper’s entire existence) that it works really, really well for me, not to mention about the same time They Live By Night and They Honeymoon Killers were being made or dreamt up in their directors’ minds. If nothing else, the ending alone justifies the story for me.

wallflower: The Tarantino of Death Proof does seem to be the guiding spirit here. I sometimes call this kind of thing a “single-incident” story; really only one thing happens. Billy Bob and Jolene get turned by a servant of Hattie, don’t like it, get married, Travis kills them. I’m completely fine with that; this is half of the Grindhouse-esque double bill of vol. 6. In addition to its brevity, there’s the one-side-or-the-other kind of morality that Death Proof had, and some awesome, iconic, ‘n’ justified violence. Travis wielding the katana (I choose to believe it’s an early Hattori Hanzo) is all the reason for being this story needs.

What makes this important as well as fun, though, is the morality. This contains some of the essential questions of American Vampire as a whole in shorter form: who am I, really? Can I live with being who I’ve become? Hattie can, and as we see in “Essence of Life,” she always can, so it makes sense that we see her here. Billy Bob and Jolene, fairly uniquely among the characters of this Cycle, cannot live with who they are and die young, but together forever. There’s a lot less characterization of Travis in this story, but he functions as a presiding spirit more than anything else. Travis here is the Elvis of True Romance (hey, another Tarantino connection), the adviser and guide to this world; one effect of creating such a complex world is that the star of one story can be a minor character in another.

Rafael Albuquerque comes back as artist here (he co-wrote it with Snyder, too) and he’s just as good as ever. His style isn’t as experimental as other volumes, favoring mostly medium shots and close-ups. I realized on this story in particular how good he is with faces, almost literally expressionistic with them. Albuquerque faces don’t just display emotion, they contort with it. He’s so suited to drawing fear and confusion, and that pays off with Jasper. He comes across as an otherworldly figure but not of the vampire’s world. So far, Snyder has been largely dealing with children and how they grow into adults, the legacy they carry on; Jasper feels like the first child who we know as a child. You could almost call his skill “shining,” and it makes me wonder if we’ll get a larger story there soon.

Avathoir: Jasper is almost 100 percent coming back, if only because Snyder has said an upcoming Third Cycle story arc is going to be heavily inspired by The Omen, which HAS to be about Jasper.

What makes Jasper so interesting to me is that he’s a character who seems to invade things where he doesn’t belong. There’s a scene detailing his situation where he’s being attacked by a group of other children before being saved by a girl, who promptly vanished. Here’s where Snyder reveals his trickery: when I first read that page, it seems to tell the story of how Billy Bob and Jolene (what great names!) met. It tricks you so that you don’t realize Jasper is the one whose depicted there until you reread it.

The only part of his story I’ve never been quite able to figure out is the ending. It’s one of Albuquerque’s odder choices to have Jasper and the cop zoomed out and that picture of the magician that dominates that panel, makes me wonder what’s being set up. I don’t think we missed anything, but rather are aware that something very, very bad is going to happen in the future.

Let’s walk down this Road a little more (I make no apologies). I think True Romance is probably the big touchstone here, with the Elvis imagery of Travis being more apparent than ever (I half expected him to bust out some ka-ra-te moves), not to mention the idea of a former prostitute falling in love with the first person who she really connected with. Unlike True Romance though, Billy Bob is more than willing to get into the shit. He’s a thief, a good one, but a thief nonetheless.

Do you also get the feeling that Billy Bob and Jolene are sort of a reflection of Henry and Pearl? They’re the same kind of people: lovers who’ve been through shit who survive by coming together, but unlike Henry and Pearl they collapse pretty quickly. It might be because their vampirism strain is much stronger than Henry or Pearl’s, or that they were both turned meant that one couldn’t feed off the other, but they can’t live with what’s happened to them the same way Pearl and Henry can. That’s interesting, considering that they’d lived a lifestyle that makes the idea of them being a vigilante vampire couple not as huge a leap.

But here’s the big difference: Billy Bob and Jolene are people who don’t want to be bad people. On some level Pearl was always the warrior she is, and Henry’s time as a soldier made him that way too. These are just children in a way none of the other vampire characters ever could be. Their pleading to Jasper to run before they kill him is one of the most heartbreaking and harrowing in the book.

Besides how strange Jasper is, and your opinions on Billy Bob and Jolene, do you think Travis has changed in the time since we last saw him? He’s now a young adult instead of a teenager (he’d be no older than 25, if my math is right), and he seems to be going on a very similar path to Felicia: he’s no longer a fundamentalist, except in the eradication of evil. He’d never have let Billy Bob and Jolene get married before, for instance, and the fact that he lets Jasper walk away is also something unlike him. It’s going to be interesting finding out what exactly he’s going to be getting up to in the future. What do you think about all this?

wallflower: first, I was surprised that he was still alive. I thought our last shot of him (“LET’S ROCK AND ROLL!”) busting into an entire house of vamps was his Last Stand. Given that he’s still with us, and probably will be for some time, I like what we have here. He hasn’t exactly developed compassion for vamps, but he has picked up some discipline in how he kills them. Old Travis may have been clever enough to start a rumor about a cure in Vegas, but he wouldn’t say “I just didn’t count on you two getting mixed up in it, though. . .I’m sorry” and he sure as hell wouldn’t demand a preacher marry Billy Bob and Jolene before killing them. He hasn’t softened, but this isn’t a vengeance trip anymore. He’s becoming something like a professional, or maybe a Sam Spade figure–the disciplined ronin on the edges of the main story.

Man, I hope something’s going on with Jasper, because Albuquerque is signaling the shit out of that all through this story. Those panels where we think we’re seeing young Billy Bob and Jolene and it turns out to be the introduction of Jasper hasn’t been part of the storytelling method before. Snyder and Albuquerque have concealed small things in action sequences but that kind of Lost-style misdirect (I’m thinking of the fourth-season episode “Ji Yeon”) is new. The moment that really hit me came from another misdirect, a more subtle one. Jasper carries around a picture of a dead stunt pilot and claims it’s his father: at first, I read the picture as coming from some adult, maybe at the orphanage, trying to give him some hope. When Travis finds out, he says “what else you been lying about lately, kid?” and Jasper has his most Damienian expression. (On the next page, there’s a similar trick, with two panels of Jasper, one where a cop can’t see his face and one where he can. The expressions are, respectively, resentment and nearly pure innocence.) I fully believe Travis’ parting words to Jasper, “I’ll be keeping an eye on you.” He’d better.

So, continuing our journey backwards, let’s pick up on the one part of volume 5 we didn’t cover, the brief closing story “The Gray Trader.” Speaking of Lost, here’s the kind of thing it used to do so well: in just a few pages, this story throws backwards and forwards, all the way back to the beginning and Will Bunting, and forward to something that looks a lot like a Las Vegas-based apocalypse. (If you want to get all meta here: Stephen King wrote the first chapter and Will Bunting is the first person we meet, and “Las Vegas-based apocalypse” describes the end of The Stand. So perhaps all of American Vampire is just a story that escaped from King’s mind.) There’s something almost cheeky about this; there always is about this kind of not-exactly a promise. (“Travis Kidd will return in From Vegas with Blood.”) What do you make of this? Do we have an idea of what the second Cycle will be like now? Do we want it to be like this?

Avathoir: We always seem to be coming back to King, don’t we? I find it so delicious that a guy who was dismissed for so long has become part of the American tradition in so many way (fuck you, Harold Bloom). But keep in mind that “The Gray Trader” came at the end of volume five. Travis’ story and the Anthology (where we briefly see the Gray Trader at the end of “The Man Comes Around”) hadn’t happened yet, so the shit that’s going down in Vegas may have already happened, though we certainly didn’t see that iconic sign set ablaze. But there’s still a lot of images that are unexplained: What looks like Skinner and someone else facing off in the desert, the search for more of the giant ancient vamps, not to mention an older Gus looking at…something off in the distance. Something’s happening, and while I have a pretty good idea what some of them are, more stuff than not is in doubt. As for who or what exactly the Gray Trader is…let me just say I want you to email me your reaction the second you find out, because OH BOY OH BOY. I wish I could see the look on your face when you read it.

Did you expect Abi to still be alive? What did you think of her, how she’s ended up spending her final days? We know that Felicia ages slowly, since she’s just a little kid when Skinner reminds Will Bunting he’s still there, and she seemingly hasn’t aged past WWII when she’s raising Gus in Paris, but the fact is Abi must be older than Pearl and Henry at least. She’s kept to herself, alone, unrepentant of how she’s lived her life, yet at the same time deeply regretful. We don’t know also who (or what) is living in her basement and that she’s keeping alive. I’m 99 percent sure it’s not Jim. It could be Henry, or someone we haven’t seen before? Since this issue is the prelude to the Second Cycle (which I’ll be sending you after I publish this), what do you expect going forward, now that you’ve read the first half of the series?

wallflower: as ever, I tend to stay away from large-scale speculation. Snyder has been careful to give us only fragments without the connections. I actually don’t think there’s going to be some kind of Standlike showdown; Snyder writes a parallel American history, not a replacement. His events take place alongside historical events, so something that large-scale is off the table. Although Gene the Bookkeeper warns that what the Gray Trader is doing could lead to an all-out attack on America (and Abi’s vision of so many hands coming out of the ground makes that disturbingly literal), I don’t think it will go that overt. Something’s coming, though, and it will involve the Vassals, Pearl, and Skinner, and given what we’ve seen so far, the loyalties will shift.

Seeing Abi and how she lives now, I remembered a line from Michael Herr’s Dispatches: “the war had only one way of coming to take your pain away quickly.” Snyder has been good all through this at showing consequences, even for the people who live and walk away. The scale of this war doesn’t express itself through space or spectacle (though there have been plenty of both in the first Cycle), but through time. Snyder blends two kinds of time in American Vampire: historical and personal. We see that right away, with Abi shutting off the TV before it starts broadcasting The Lone Ranger. She knows all about lone Rangers, thank you very much. We keep seeing the humans who live out of their world into new ones, but who still carry the scars of their battles. (The only one who seems to have gotten away healthy-like is Will Bunting, the storyteller, who ends his days fishing in the Florida Keys.) We also see the vampires like Pearl and Skinner and Cal, who don’t get to die but still have to change; in “The Man Comes Around,” Skinner says “I suppose there’s perks to growing up.” There are perks, but there are also responsibilities; and we’re heading into an era of history where America will have more of both. That means they will too.