Like in The Martian, the solitary protagonist, Sam Bell, of Moon (2009) longs to return home to Earth. But Moon presents a different, more fundamental, problem to solve: Who am I? As we will find out, a name is just a label that pretends to hold together a fragmented self-image.

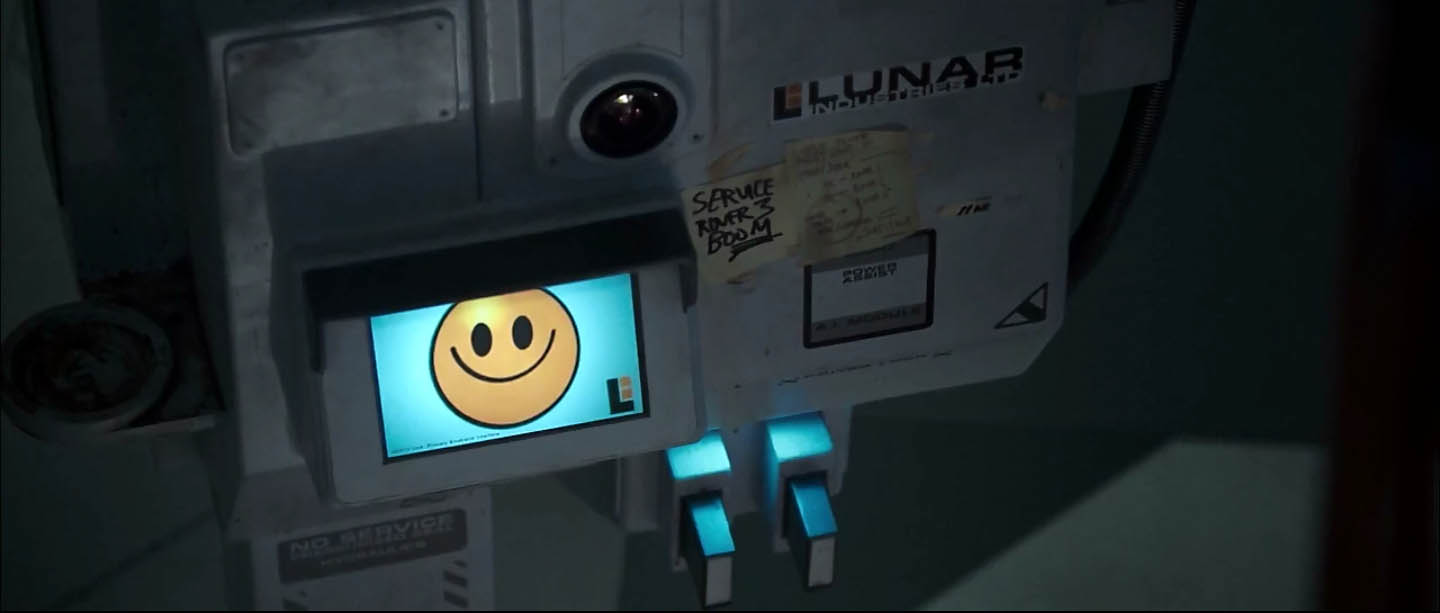

We know that Sam’s three-year contract supervising the machines that mine lunar energy is near an end. He transmits and receives recorded messages to and from his wife—in these distant, rather brief, exchanges we can feel his intense loneliness and isolation. His only companion is Gerty, an android whose prime directive, he repeatedly tells Sam, is to take care of his every need.

Time passes slowly. While Sam’s quarters look lived in, their functionalist design and numbing color pattern have all of the appeal of a roomy prison cell or barracks. It would certainly be hard to make this living arrangement feel like home. The drudgery of the work adds to the sense of endless boredom and frustration.

Call it a space-age case of alienated labor: Sam is marooned on a remote lunar outpost so everyone on Earth can benefit from a clean source of energy. The company’s advertisement, which we see at the beginning of the film, implies this is, of course, all for the greater good.

Sam, however, is beginning to break down. He hallucinates an image of a dark-haired woman, causing him to scald himself with hot water from the coffee maker. When a mining machine malfunctions, he goes out to investigate—and sees an image of himself, causing the rover he is driving to crash.

Arguably the speculative insights about identity that begin at this point outweigh the logical limits of the narrative action. Director Duncan Jones (son of David Bowie) faces a challenge: to convincingly portray what happens from here on out is a difficult trick to pull off in any film, much less one shot on a fairly low budget. Yet this apparent shortcoming may be seen as a virtue: we can’t simply sink into a world of extravagant special effects and watch uncritically. Rather, we feel separate from Sam—and detached from what happens to him.

He wakes up and is lying on a hospital bed back at the base. Gerty tells him that he’s had an accident and suffered some memory loss. Curiosity mixes with paranoia, as he wants to figure out what’s going on. He makes plans to investigate the crash scene, but Gerty tells him he is prohibited from doing so on account of orders from the company.

This is a clever screenwriting touch by Jones and Nathan Parker, for it makes Gerty appear in cahoots with the shady company executives. Voiced by Kevin Spacey, Gerty has an unctuous tone that would most likely get on anyone’s nerves—his surface niceties echo the platitudes of the execs. But this is one of many instances of things not being what they seem.

This is a clever screenwriting touch by Jones and Nathan Parker, for it makes Gerty appear in cahoots with the shady company executives. Voiced by Kevin Spacey, Gerty has an unctuous tone that would most likely get on anyone’s nerves—his surface niceties echo the platitudes of the execs. But this is one of many instances of things not being what they seem.

On the pretense of going outside to repair a leak that he has deliberately created, Sam discovers that the body in the crashed rover looks exactly like him. He brings the body back to the base.

As Sam, Sam Rockwell makes each of his character’s two selves distinct enough as each takes turns accusing the other of being a copy. Aided by a split-screen effect, the mood shifts from suspicion to an uneasy trust, a feeling of solidarity as both realize they’re in it together. There’s no distinction between a real and illusory sense of identity. Each of the two copies of Sam is a character in his own right, each capable of making choices and acting on his own volition.

Sam’s self-realization is assisted by Gerty, who, rather than being a malevolent force, like HAL in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), helps him to access restricted databases. Sam sees recordings of himself, getting older, more disassociated, and sicker. By now, Sam is no longer looking very well, which stands in contrast with the person he rescued from the crashed rover.

There’s a key line of dialogue that unlocks the mystery: the rescued person tells Sam that his body wasn’t supposed to be found. Although the film, to its credit, does not spell everything out, it seems certain that the memory of the crash triggers an awakening of each Sam and that each copy has a three-year life span, due to what appears to be radiation poisoning from the lunar environment—possibly from the mining process.

This all means, of course, that Sam is a clone of some human that we never see. The carefully fabricated illusion that the company has constructed for its solitary labor force begins to unravel. When Sam drives past the towers that block direct communications, he can transmit live to home. He discovers that his wife died some years ago, and his daughter has grown into a teenager. A voice off screen, perhaps the human version of Sam, asks his daughter with whom she is talking. Sam, afraid of being found out, ceases transmission.

Such shifts in relative time explain why we knew so little about Sam at the beginning: he has only been given enough implanted memories for him to be a useful temporary worker—a scheme for exploiting labor that would make even a corporation like Wal-Mart jealous. The ethical implications of cloning here come to light. If we can create exact copies of ourselves, do we have a real self? On what grounds can consent be given if a clone is going to be subject to forced labor and a considerably painful death?

Unfortunately the film sidesteps these questions with a closing set piece characteristic of “harder” SF: the race against time to escape before the company goons arrive to restore order and destroy the sentient clones. The lines are now more clearly drawn: Sam against the company. Or are they really? We cheer for Sam, while knowing, or conveniently forgetting, that Sam acts more human than the humans who would sentence him to death for exposing their heartless cruelty.

Moon still feels more complex than the if P, then Q logic of The Martian. Sure, The Martian inserts scenes of dramatic struggle in between correct thinking and correct actions, which energizes its man-against-Mars plot. But the hall of mirrors perspective presented in Moon would ask further: who—or what—is doing the thinking and acting here?

In addition, Moon shows us what future colonialism might look like, as those sucking the energy resources out of another planet would rather be anywhere else. They dream of escaping to Earth, rather than from it. In this way, their desire reflects back to the longing of past colonizers, exiled on the far edges of empire, to return to what they would call a “civilized” world.

And unlike The Martian, Moon gives us the discomforting reality of what will happen if we don’t take concerted steps to reduce our energy consumption. Yes, the solution of lunar mining is, admittedly, preferable to a global war over limited energy resources. Moon, however, pulls no punches in arguing that there is an ethical cost to keeping the peace.