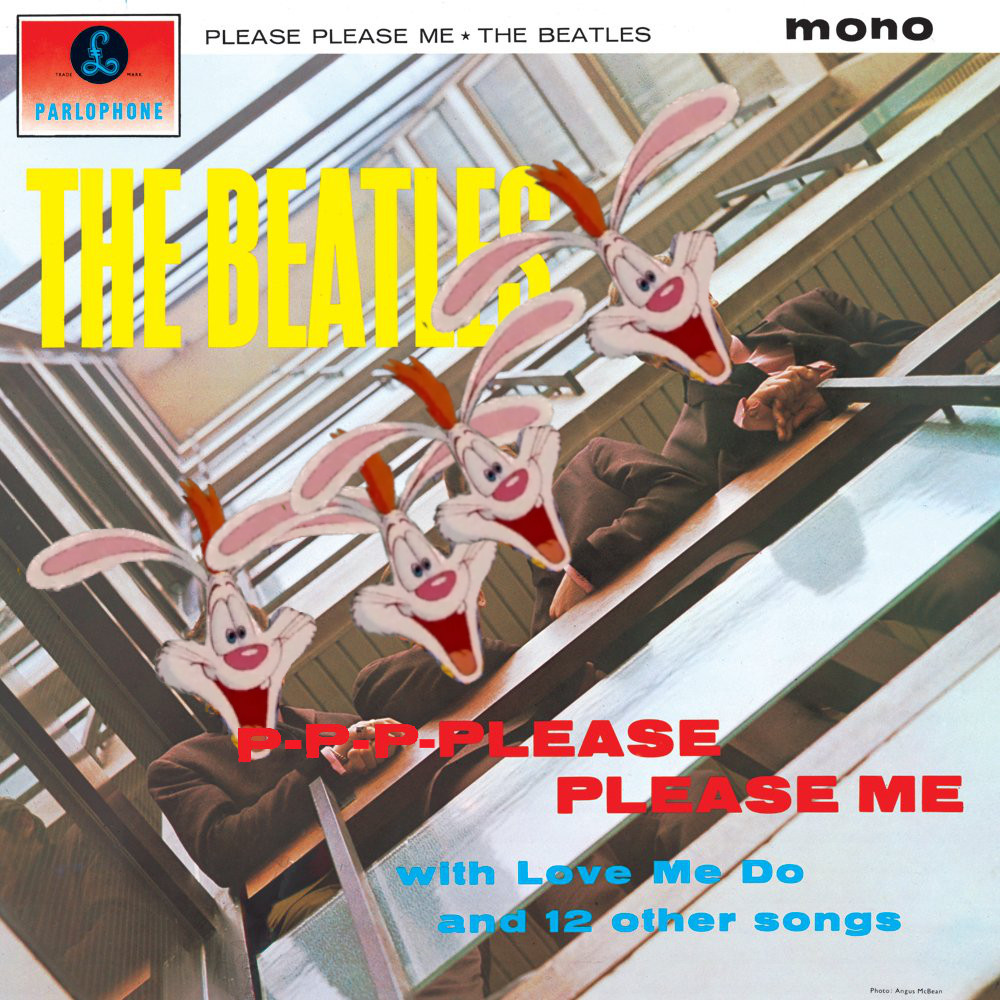

I know I’ve spent this whole series trying to prove that the Dark Age of Animation was not, in fact, an error. And I would never suggest it was, never, ever — only, as Roger Rabbit would say, when it’s funny.

Oliver and Company shows Disney’s core team can’t take the credit for animation’s incredible resurgence in 1988. Instead, the credit goes to an outside contractor. Just about everyone agrees Who Framed Roger Rabbit is a great movie, but it’s easy to overlook how much it changed the course of the whole medium. Legendarily obsessive animation director Richard Williams got the budget to realize his most imaginative fantasies (and then went over it), kicking an industry that had been racing to the lowest common denominator for decades into high gear.

Williams, producer Stephen Spielberg, and director Robert Zemeckis’ obvious love for the cartoon characters of their youth, from Bugs Bunny to Mickey Mouse to Betty Boop to the Reluctant Dragon, and their proof that you could create new characters like Roger, Jessica, and the Weasels who fit right in was equally inspirational. The following decade would see an explosion of classic-inspired cartoons from Ren and Stimpy to Animaniacs to the Fleischer-Superman-inspired Batman, not to mention outright takeoffs like Space Jam, Cool World, and Disney’s own Bonkers. It’s a shame they never reached enough critical mass to become a genuine genre: the possibilities of a world of humans and living cartoon characters are endless.

I’ve talked, maybe too much, about Williams’ beautifully obsessive, excessive attention to detail. With Roger Rabbit, he finally had the budget to realize his wildest visions (until he exceeded it and got the boot, as is his custom) and a platform that would show every other animator what their medium is capable of. He hits the ground running with the opening “Baby Herman” short: just watch as the “camera” follows Roger, his tail on fire, in circles around the kitchen. No computer cheats here — Williams’ team redrew that kitchen 24 times a second, down to the complexities of the checkerboard floor, Roger’s reflection in it, and the increasing number of billowing smoke trails. There’s a wonderful moment in the documentary Behind the Ears where Williams recalls Zemeckis asking if he could animate characters moving through a live-action world because everyone else had told him no. Williams responded, “Oh, it’s possible, it’s just a lot of work,” and he seems almost gleeful at the thought of putting in extra hours.

It’s fitting Jessica performs at the Ink and Paint Club, because Roger Rabbit exposed all the possibilities of that often-overlooked side of animation. We’ve already seen how much shading and texture enriched the characters in Roger’s Japanese competitors, but that was a lost art in Hollywood by the time Williams came to Disney. The major studios gradually phased out the beautifully subtle watercolors of the ‘30s and early ‘40s for less expressive materials by the end of the decade. Once the ‘50s rolled around and animation absorbed the principles of mid-century modern minimalism, anything too complex to recreate in crayon was hopelessly uncool.

But fuck whatever the trends may have said, watching the subtle variations in color as they’re repainted hundreds of times is cool and Williams recognized that. A lot of people assume Roger Rabbit invented the combination of live-action and animation, but that idea’s as old as animation itself. What Roger Rabbit did invent, or at least perfect, was integrating the lights and shadows from the live-action footage into their animation. Disney started referring to especially brilliant attention to detail as “bumping the lamp” after a scene where Bob Hoskins as PI Eddie Valiant bumps a lamp and the shadows play across Roger’s animated body in perfect sync. Thirty-odd years later, there’s still no animation that uses color quite like Roger does, with the different varieties of sheen reflecting off different textures, with that beautiful shimmer that reminds you this is the work of human hands with all the inconsistencies that comes from it. Disney would learn from Williams’ example and introduced subtler shadings into their ‘90s. But they took the digital shortcut with their new CAPS system, and the missing human touch is palpable. As good as Disney’s ‘90s films are, none of them capture the beauty of Roger.

Roger Rabbit is, if anything, even more personal to me than Totoro. My parents had the VHS, and I watched it all the way through once and scared myself shitless. After that, I was happy just to watch up until Eddie left the Maroon studio over and over again — and why not? That has more inventions in ten minutes than most movies spread over two hours.

A trip to Mickey’s Toontown in Disneyland and a few years of getting older and wiser (relatively — I was seven) convinced me to give it another shot, and I was hooked. It became the basis for my own personal mythology of a world called Fantasy (I never said I had that much imagination) where every fictional character lived, including the residents of Toontown. I was all in on anything that even vaguely resembled Roger — the aforementioned Bonkers, a Tiny Toons episode where Babs and Buster Bunny appeared on a live-action show and called themselves “toons.”

Part of that was the thrill of feeling like I was getting away with something, watching a grown-up “tale of greed, sex, and murder.” This became hilarious to me rewatching it now that I actually am (in theory) grown-up because half the fun is watching Zemeckis hammer a film noir story into a kid-friendly shape — best of all when Eddie catches Jessica Rabbit and Marvin Acme “playing patty cake” and it turns out not to be a euphemism.

This doesn’t make me immune to the movie’s flaws. The bean-counters were probably right to get nervous over Williams’ spending, because it doesn’t seem to have left much over for the period sets, which rarely look like anything but sets compared to the more lush, lived-in environments of contemporary recent-history movies like The Untouchables or the Indiana Jones movies, give or take the wonderfully grungy dressing rooms beneath the Ink and Paint Club. Hoskins and costar Joanna Cassidy may not have faces that know what text messaging is, but they at least know what a walkman is.

Roger Rabbit is many things, most of them great, but one of them is a racial allegory, which doesn’t seem to have half the thought put into it as any frame of the animation. The Toons are clearly stand-ins for various real-life minorities’ struggles in Hollywood — the Ink and Paint Club, with its “toon revue, strictly humans only” is an obvious reference to the segregated Cotton Club, and Toontown resembles any number of ethnic neighborhoods, down to almost being destroyed for gentrification. Even as a child, I could hear the echoes of a slur in the way Bob Hoskins growls “Toons” when he first appears — and now I know I know it is one letter away from a slur, one that’s stuck especially to Black entertainers.

At its heart, Roger Rabbit is a “bigot learns a lesson” story, and wherever you stand on the plot in movies about real minorities, even Green Book didn’t include Mahershal Ali sobbing, “If a Toon killed my brother, I’d hate me too!” Zemeckis certainly doesn’t seem to have thought through the implications of connecting cartoon characters to Black performers in Hollywood. In both cases, we have a race that subsists on humiliating themselves in slapstick comedies for a white (read: human) audience. In real life, that’s the result of active discrimination from more serious roles, let alone more important jobs, and centuries of blackface minstrelsy. In Roger Rabbit, Toons just dance for the humans’ entertainment because they love it so darned much!

And then there’s Judge Doom. A fantastic performance by Christopher Lloyd. A great, terrifying twist when we learn he’s a toon himself. (Everyone remembers the eyes, but let’s not sleep on the moment Zemeckis introduces a third medium to the mix for the deeply creepy flat, stop-motion Doom.) But there’s one problem: It leaves this story about human prejudice without a single human bad guy. Doom goes from an indictment of the racism of law-and-order and big-business types to a rogue minority. And Eddie’s reaction (“Only a Toon’d be screwy enough to come up with that freeway idea”) suggests he hasn’t actually learned all that much.

Even in our thinkpiece-heavy times, these failures don’t seem to have so much as dented Roger Rabbit’s legacy. In a way, that’s fair, because it succeeds so spectacularly at every other level. We’d see Williams’ innovations pay off over the course of the next decade. But, of course, he never did. Disney built him up as long as he was useful and tore him down the minute he wasn’t. Now that Williams had the clout to finish his decades-in-the-works The Thief and the Cobbler, Disney swooped in with the suspiciously similar Aladdin. Williams’ backers panicked that his perfectionist schedule wouldn’t get him to theaters in time for general audiences to see his labor of love as anything but a cheap cash-in on Disney’s film. He lost control of his life’s work with just fifteen minutes left to animate. The studio failed to beat Aladdin anyway, and adding new Disney-ripoff songs couldn’t have helped.

Bluth had similarly showed Disney the way out of the dark age, and they thanked him just as kindly. Michael Eisner demanded Oliver and Company stay in theaters until the following summer if it meant outgrossing The Land Before Time and An American Tail combined. (It managed to get halfway to that goal, and just barely.) As Disney’s star rose thanks to their plundering of his techniques, Bluth’s fell. His projects flopped and he adjusted his ambitions accordingly until he was stuck in a death spiral of mediocrity that was only (and only briefly) broken by shamelessly stealing the ‘90s Disney formula for Anastasia.

Because of that, it’s hard to see the closing of the Dark Age as anything but bittersweet. The mean quality of animation rose to its former heights; but it came at the price of that Disney formula overtaking everything. Smaller studios that once saw endless possibilities in the medium settled for chasing the Disney dollar with increasingly shoddy imitations. I’m back once again to asking — did the Disney Renaissance end a Dark Age for the medium or begin one?

You can find my further thoughts on Who Framed Roger Rabbit? here.