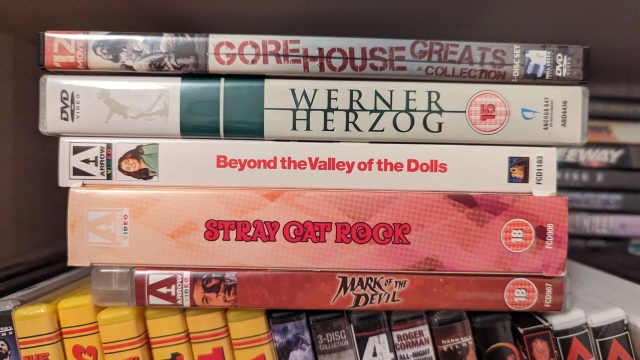

I have far too many unwatched movies on my shelves. Follow me as I attempt to watch all of the ones from the current Year of the Month and figure out what they say about the year in question! Part four launches into 1970, featuring such well-remembered* classics as Blood Mania, Mark of the Devil, Even Dwarfs Started Small, Beyond the Valley of the Dolls, and a disturbingly large chunk of the Stray Cat Rock series!

* memories may vary

One Nine Seven Zero! The ’60s may be over, but judging by this set of movies, the psychedelic drugs have not worn off just yet. I feel like I can confidently describe all of these movies as “a trip,” and I can cheerfully report that my mind has been expanded. But let’s start gently with Blood Mania, which creates expectations with its title that it can’t possibly meet. Is there blood in this movie? Eventually, a little. How much mania is featured? A fair amount. But Blood Mania? That conjures up visions of Herschell Gordon Lewis’ amateurish gorefests, when what this movie actually delivers is a mix of soap-opera plotting, occasional murders, and triple-threat star, writer, and producer Peter Carpenter indulging in frequent sex scenes with a variety of beautiful women. It’s one of those movies that is a struggle to actively pay attention to, but plays well in the background — it has a vibe, it’s well-shot, and the score is consistently very good, a mixture of jazzy guitar and drums with some wonderfully strange electronic elements. There’s something oddly compelling about Maria De Aragon’s performance too: she plays the titular blood maniac with a calm detachment rather than leaning into the madness, and it’s very effective. The film does eventually crank up into a higher gear in the last ten minutes or so and delivers some thrills — not really enough to recommend it as a whole, but it does have a certain charm.

Mark of the Devil is definitely a bad trip. 1968’s Witchfinder General was a big hit in West Germany, leading several German studios to launch productions that could charitably be described as spiritual sequels. Filmed in Austria, starring a broad selection of international talent and directed by an Englishman, production was hampered by the sheer number of languages being spoken on set. Nevertheless, it’s an effectively nasty piece of work, with torture sequences that push beyond Witchfinder, to the extent that it received William Castle-style over-the-top promotion, sick bags being handed out to anyone brave enough to catch a screening. It’s a pretty good-looking film with an appropriately overwhelming score and sound design, but it’s the cast that really elevates it — a murderer’s row of character actors contrasting wonderfully with the glamor of Serbian actress (and possible witch) Olivera Katarina and the impossibly striking young Udo Kier as the protagonist, a conflicted witch hunter only just beginning to realize that his peers are incredibly corrupt and his mission might just be fraudulent.

The previous installments of Tales from the Backlog have all included an interesting late-period film from a noted auteur, but 1970 dares to be different! Even Dwarfs Started Small takes us right back to the early days of Werner Herzog’s career. His debut, Signs of Life, was a critical and commercial success a couple of years earlier — it seems a little harder to find than most of his work now, but was enough of a hit at the time that he was able to really get weird with his follow-up. Even in a career as consistently eccentric as Herzog’s, Even Dwarfs Started Small is a stand-out: it follows a swift descent into anarchy as the patients of an institution depose their authority figures and embark on a chaotic spree that largely involves vandalism, animal cruelty and — this cannot be overstated — absolutely shitloads of maniacal cackling. As hinted by the title, the film has an all-dwarf cast, but this doesn’t particularly play into the plot — it’s just another element of the film’s peculiarity.

The production of the movie sounds as strange as the end result, with Herzog notably responding to a number of on-set accidents by promising to throw himself into a field of cactuses if the film was successfully completed (a promise that was fulfilled, which should come as no surprise to anyone who has watched Herzog cook and eat his own shoe). The end result is a bizarrely compelling piece of work, full of striking scenes but also confrontational elements that make it a tough watch, particularly the treatment of animals but also that non-stop cackling. Herzog’s later films frequently incorporate elements of the strange mayhem found here, but experiencing it in its purest form is more than a little exhausting. It’s unlike anything else though, and reaches a weirdly transcendent level of chaos at times — Harmony Korine has apparently listed it as a major influence, which is perhaps the best possible summary of the film’s strengths and weaknesses.

Perhaps the most interesting thing about Japan’s Stray Cat Rock series — certainly from a Year of the Month perspective — is that it comprises five films, and somehow four of them were released in 1970. Part of a wave of Japanese movies inspired by the violence and counter-cultural themes of New Hollywood, the first movie (Delinquent Girl Boss) follows a girl gang as they team up with a female biker to battle rival gangs, injustice, and fixed boxing matches. It sets a loose template for the series to follow — violence, musical interludes, energetic camera work, downer endings — and also helped launch the career of Meiko Kaji, who would go on to star in movies such as Lady Snowblood. The first movie was successful enough that a sequel (Wild Jumbo) was rushed into production but oddly, it pivots into more of a heist plot and a mixed ensemble cast with Kaji not getting as much screen time, despite being the breakout star. It’s still stylish and energetic, but the plot — perhaps understandably, given how quick they were churning these movies out — feels like they’re making it up as they go along. The third movie, Sex Hunter, gets things back on track with a return to the girl gang formula and Kaji back in the thick of things. As the title suggests, it’s the horniest of the series despite a serious plot that deals with simmering racial tensions, and it hits a perfect seam of glorious vengeance during a scene where Kaji rescues her trapped gang members using a barrage of Molotov cocktails. The final outing for the year, Machine Animal, feels like the most balanced — Kaji’s gang attempt to rip off some drug dealers only to find that they’re kindred spirits, and they team up in an attempt to foil a rival gang and get the dealers out of the country. The writing’s stronger, the characters are more fleshed out, Kaji gets to sing a song, and there’s an awesome motorcycle chase — what’s not to like? The series would conclude with one more movie, but it came out in 1971 so who cares? We’re talking 1970, baby!

Finally, back in the US, Beyond the Valley of the Dolls feels like it’s shooting for a similar audience of rebellious young people even if the plot is a rise-and-fall/dangers of stardom story rather than gang warfare. Beginning by cheerfully informing the audience that it is absolutely not a sequel to Valley of the Dolls — much appreciated for those of us who couldn’t be bothered to see it — it quickly launches into a blistering satire of the entertainment industry that feels both extremely of its time (if there is a more 1970 movie than this one, I’m not sure I believe it) and also ahead of it — the quick editing, snappy dialogue and over-the-top characters here feel like a huge influence on half of the movies released in the ’90s, but particularly stuff like Josie & The Pussycats. Also, much like that movie, it gets the music just right: every song that the fictional band performs here genuinely feels like it could be a hit, which makes their slightly ridiculous rise to fame ring true regardless. Of the films covered here, this is the one that has achieved genuine cult classic status, and it’s absolutely deserving: Roger Ebert’s flirtation with screenwriting results in some hilarious dialogue, and Russ Meyer’s direction matches it all the way, luxuriating in the absurd excesses of show business and treating the increasingly bizarre plot with absolute sincerity so that every melodramatic moment is elevated to glorious camp. Though it’s furiously paced right from the start, the film still finds a way to move into a higher gear for a deliriously insane finale that has to be seen to be believed — a wonderful snapshot of a gloriously excessive era.

So, what do these movies tell us about 1970? Well, a big shift had recently taken place in Hollywood with movies like Bonnie & Clyde pushing the boundaries of violence, sex, language, and general on-screen behavior. It feels like pretty much every movie here is exploding out from that big bang, seeing what they can get away with and how much they can, like, freak out the squares, man. It feels like most of these movies either revolve around psychedelic drug use, are soundtracked by psychedelic drug users or — in the case of Even Dwarfs Started Small — push the brain into a similarly rearranged state as drug use itself. A magical time for really strange movies. A really bad time for hangovers, probably.