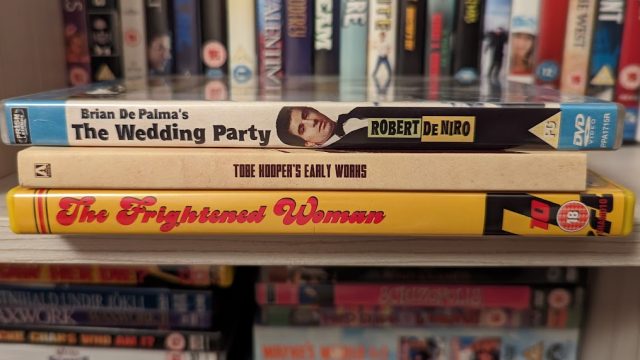

I have far too many unwatched movies on my shelves. Follow me as I attempt to watch all of the ones from the current Year of the Month and figure out what they say about the year in question! Part five takes on 1969, with peculiar early works from Brian de Palma and Tobe Hooper, plus an Italian erotic thriller!

Nineteen Sixty-Nine! Nice! Haha! Nixon. Woodstock. Charles Manson. A man on the moon! The Beatles on a roof! Truly a year when you Google “biggest news stories of 1969” and the hits just keep coming. But also an important year for brand new filmmakers ending up stranded on my neglected shelves… kinda. Because while Tobe Hooper’s Eggshells is unambiguously his debut, The Wedding Party features the first feature film work from both Brian De Palma and Robert De Niro but had such a delayed release that both of them were at least somewhat established by the time it finally came out. Confusing! The Frightened Woman was also a debut feature, for Italian director Piero Schivazappa. His is sadly not a name with as much cultural cachet, but — spoilers for the article you’re currently reading — his film kicks the absolute shit out of the other two. Let’s go!

Eggshells is a perfect late-sixties time capsule that also feels like it’s been beamed in from another universe. Obviously when most people think of Tobe Hooper today, they go straight to The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, his breakthrough sophomore film from five years later. Hooper’s post-Chain Saw career largely stuck to the horror genre, but his first film is a fascinating experimental hippie drama, almost plotless but endlessly visually striking. Hooper’s work has had a bit of a reappraisal in recent years from the same group of young cinephiles that yell about the “vulgar auteurism” of Paul W.S. Anderson and company, and it’s true that even Hooper’s less beloved, chainsaw-lacking movies are full of striking visuals even when their overall quality is a little questionable. This debut film coasts almost completely on those visuals, using trick photography, in-camera FX and psychedelic filters — plus some fittingly strange sound design — to elevate a paper-thin narrative about a hippie commune.

The film suffers when it actually pauses to let people talk. The wandering conversations that occasionally swim into focus are perfectly tedious and perfectly capture how I imagine it must have felt to be part of a hippie commune on the days when the psychedelics ran out. But the experimental stuff is compelling, and much like Texas Chain Saw, this film somehow seems to warp time around it — despite the lack of a narrative, I found myself reaching the end of the 90 minutes in what felt like a much shorter time. It’s also quite fun that this movie starts just like Hooper’s masterpiece ends — with a young woman climbing into the back of a flatbed truck and escaping the country. (In this case her motivations are slightly different.)

The Wedding Party is also a fascinatingly experimental pseudo-debut, but in quite different ways. De Palma is one of three credited directors alongside his theater professor Wilford Leach and fellow Leach student Cynthia Munroe, and it feels very much like the product of enthusiastic, talented newcomers with plenty of ideas but a clear lack of focus. It begins with intertitles and a sped-up sequence that pays homage to silent comedy, but other scenes seem more indebted to screwball, the French New Wave, or contemporary American cinema, and frequently the influences are combined or temporarily forgotten in ways that make the whole experience pretty uneven.

There’s good stuff in there, though. The silent comedy homages are energetic and fun, and the New-Wave-inspired editing makes the ensemble party scenes compelling, even if it also sometimes leads to decent punchlines getting cut before they have a chance to land. De Niro and future De Palma regular William Finlay play the groom’s two best friends, and the way they argue for or against marriage in direct opposition to the groom’s feelings at any time make for a fun dynamic. But at other times the film can be abrasive or tedious. One long sequence in the second half is a perfect example: we follow the drunken groom as he attempts to seduce the bookish organist, only to get cold feet once he’s made it up to her bedroom, at which point the dynamic shifts and she tries to seduce him. It’s funny in concept, tedious in execution and has none of the inventive visuals or edits found earlier in the film. De Palma seems to have been the main creative force of the credited filmmakers — the belated release was apparently caused by him demanding final cut, which is amusingly audacious — but the inconsistent feel of the film does feel like it might have been a result of the various voices involved in the film, and their combined lack of experience.

The Frightened Woman (aka The Laughing Woman, confusingly — and originally titled Femina Ridens) feels like a far more cohesive vision was behind it, despite another relatively fresh-faced director. Schivazappa had done a bunch of work in television before making his feature debut, including some assistant-director work alongside genre legend Mario Bava. No doubt this experience helped him approach his first big cinematic project so confidently that it feels not only incredibly assured, but ahead of its time.

The film starts out, worryingly, with a creepy businessman inviting a young female employee to his home to pick up some documents, then immediately imprisoning her in his futuristic torture-house. For a while, it seems like this might be a forerunner of the endlessly unpleasant Torture Porn subgenre but Schivazappa has more interesting things on his mind, and the seemingly one-sided conflict slowly develops into a more complex game of wits. There’s a wonderfully twisted sense of humor at play here as the film’s two leads — Dagmar Lassander and Philippe Leroy — toy with each other, and if it weren’t for the extremely ’60s stylings then it feels like this film’s fascinatingly odd, kinky sexual politics would be far more at home alongside Paul Verhoeven, Adrian Lyne and the gloriously sleazy wave of ’90s erotic thrillers.

The Frightened Woman is a difficult film to describe further without launching into spoiler territory. For the most part it’s a two-hander that feels like it could easily fall apart without such strong performances, but the combination of Lasssander, Leroy, and some sharp writing keep the audience guessing as the balance of power continues to shift and the plot becomes wonderfully ambiguous and strange. Leroy’s futuristic home is the setting for the majority of the movie, and it’s beautifully (and creepily) designed, and as per most Italian genre fare, the score is fantastic. It’s a real shame that Schivazappa’s later career doesn’t seem to have delivered on the promise shown here. He drifted back into Italian TV work that doesn’t appear to have made much of an impact elsewhere. But this film is a real gem that must have really raised some eyebrows back in 1969 even if, in retrospect, that kinda seems like the perfect year for it.

So what do these films tell us about 1969? Well, the two American films here are both clearly in thrall to Godard and co. which makes it all the more interesting that the European film seems to be forging ahead on its own path. Eggshells and The Frightened Woman are both clearly in conversation with the era of free love and changing gender dynamics whereas The Wedding Party — shot six years earlier, lest we forget — feels like a throwback to a more reserved time. All three of them have a sense of freedom to them: the Production Code had recently ended and New Hollywood was in full swing, which surely must have given Hooper and De Palma more room to experiment and get weird. Meanwhile, Italian cinema seems to have been weird since they first got their hands on a camera, but even in such unrestrained company, The Frightened Woman manages to feel like an outlier in the best possible way.