I have far too many unwatched movies on my shelves. Follow me as I attempt to watch all of the ones from the current Year of the Month and figure out what they say about the year in question! Part two takes on three of 1947’s “movies that exist”: The Brasher Doubloon, The Web, and Monsieur Verdoux.

Nineteen Forty-Seven: The second World War is over! The Cold War begins! A time of rebuilding, paranoia and post-traumatic stress disorder is at hand. As much of the world sinks into an uneasy peace, the entertainment industry feels the strain as the “Hollywood Ten” become the first victims of the House Un-American Activities Committee’s anti-Communist witch hunt. But what are the people who are still allowed to work in Hollywood doing?

Why, low-budget noir of course! The ’40s had already given us a couple of classic Raymond Chandler adaptations — Murder, My Sweet and The Big Sleep — plus the POV-shot curiosity Lady in the Lake. But before any of those, two earlier adaptations had taken Chandler’s source material and swapped in other popular detectives of the time: an early take on “Farewell, My Lovely” became The Falcon Takes Over and detective Michael Shayne subbed in for Marlowe in an adaptation of “The High Window,” retitled Time to Kill. This means that The Brasher Doubloon somehow manages to be the second adaptation of “The High Window” in the five years since it was published. This one’s a brisk 70-minute affair that tells Chandler’s story pretty faithfully.

Star George Montgomery was a prolific actor who started out as a stuntman before breaking into Westerns, but never really broke through to popular leading man status. As Marlowe, he’s alright — a little too upbeat perhaps: his wisecracks work, but they’d be considerably more effective with a little more world-weariness to his delivery. The female lead, Nancy Guild, was starring in only her second film: she does good work in a tricky role and has great chemistry with Montgomery that goes a good way to making up for his slightly misjudged cheerfulness.

Unfortunately Brasher Doubloon doesn’t have too much shadowy visual style to hide the cheap sets, although there is one interesting stylistic choice — basically every exterior shot features strong winds. I was curious about this, wondering whether it comes from the novel and the filmmakers decided to roll with it. I checked, and on the very first page it mentions the weather being “exceptionally still”… which is hilarious. Aside from that weird contrarian decision, it’s a solid but unexceptional detective story — the short running time and the solid plot keep it entertaining throughout but it falls short of the better-known Chandler adaptations of the decade. Marlowe-mania seems to have dried up in the wake of this film: Chandler published a couple more novels in the years that followed but the detective wouldn’t see another cinematic until the late ’60s.

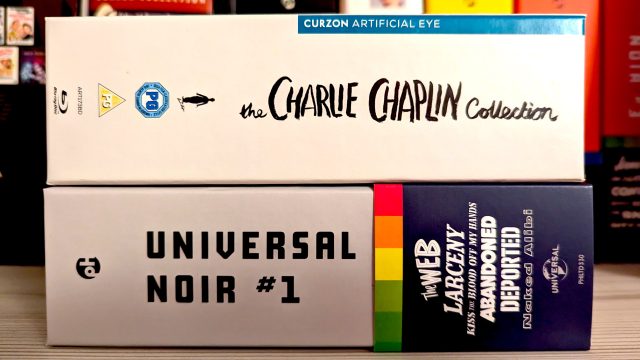

Meanwhile, over at Universal, The Web may not have an established private eye but it does have Vincent Price as a shady businessman. Six years before Price’s rise to legend of horror, he showcased his capable villainy in more grounded surroundings. He offers Edmond O’Brien’s small-time lawyer a deal that seems too good to be true, and within hours, O’Brien has killed a man, fallen for his new boss’s secretary and found himself in an impossible situation: revealing the true details of the crime would only implicate him further.

It’s a wonderfully twisty premise and the cast combine to elevate it to near-greatness — Price’s calm cruelty perfectly foreshadows his future roles and O’Brien is gruffly charming as he works to dig himself out of trouble without the ground collapsing under him. It’s Ella Raines who almost walks away with the movie, though — she starts as Price’s faithful assistant but really sells the character’s emotional arc as she begins to fall for O’Brien while also realizing that Price may just be rotten to his core.

The always-welcome William Bendix rounds out the main cast as the conflicted police lieutenant who knows he’s risking everything by investigating the town’s richest and most powerful resident. But even the people who show up for a single scene seem determined to steal it — it’s the kind of movie where every minor character gets a moment in the spotlight as O’Brien’s investigation takes him from one glorious oddball to the next. A superbly entertaining noir, and one of Vincent Price’s finest early roles.

Thinking about the world of 1947 before I launched into these movies, I found myself wondering how much they’d exist in the shadow of World War II. While there are certainly noirs that deal with the fallout of global conflict (for example, ’47’s absolutely brilliant Dead Reckoning), neither of these two really get into it all. Conversely, I thought maybe Charlie Chaplin had already gotten his thoughts on the war out of the way in 1940 with The Great Dictator, but clearly it was still very much on his mind.

Monsieur Verdoux, Chaplin’s extremely strange serial-killer comedy, started life as a potential collaboration with Orson Welles. Welles was fascinated by the life and crimes of French serial killer Henri Désiré Landru, who romanced and killed at least ten women (and one’s teenage son) around the time of the first World War. The idea of Chaplin playing against type in a dramatic role was interesting to both men, but they couldn’t agree on the details, and eventually Chaplin decided to make it as a comedy (Welles still gets a “story by” credit but there are differing accounts on whether he actually wrote anything).

Verdoux is by no means the first comedy to revolve around murder: Arsenic & Old Lace had made it work a few years earlier (albeit without the killer for a protagonist) and Ealing Studios would gleefully embrace black comedy a couple of years later to great effect. But Chaplin’s film is unusual in its deep sympathy with the lead character. Verdoux kills to feed his family, you see — he lost his job during the Great Depression, and the only way he can support his young son and wheelchair-using wife is to…repeatedly seduce and then murder wealthy women.

Chaplin’s comic skill makes it work, most of the time. But it’s a deeply perplexing watch — one might expect a black comedy to be a little lighter on the sincere, sentimental qualities that his earlier comedies had in abundance, but oddly, Verdoux has plenty of that too. And, somehow, most of that really works too! When he meets a young woman (listed only as “The Girl”) who has had a hard life, he decides — just for once — not to go through with a planned murder. Because they’re the same, you see? She loved her invalid husband, and he kills women for money. The same! And yet…somehow, Chaplin does find a weird poignancy in this that really resonates.

I assume this unique quality has led to Monsieur Verdoux’s reassessment as one of Chaplin’s finest films after a lukewarm initial reaction. I found myself a bit more mixed on it — the direction feels a little stagy, especially early on, and when World War II does make an appearance towards the end, Chaplin once again uses it to draw some strange parallels between his character’s actions and humanity as a whole. But he was clearly processing some big ideas, and the ambition is laudable even if the result is likely to continue to divide audiences for the rest of time.

So what do these three movies tell us about 1947? I dunno man, it seems like a pretty mixed up time. People were dealing with some shit! Philip Marlowe was weirdly cheerful, Vincent Price hadn’t even entered his most powerful phase yet, and Charlie Chaplin was killing women right, left, and center. It must have been a deeply strange time to be alive.