Summer Of Nathan is a tribute to the work of former Dissolve (and current freelance) writer Nathan Rabin, curated by Sam “BurgundySuit” Scott, consisting of Dissolve commenters 😞 Solute writers/commenters writing their own versions of his article series. Recent entries from Gilllianren and Grant “wallflower” Nebel have posted on The Solute. Additional entries have been posted in various comment sections of The Dissolve, so if you have a link to one, put it in the comments here!

Nabin covered The Simpsons (Classic) beat for the AV Club for Seasons 1 – 5, Ep. 21.

You probably don’t need me to tell you that The Simpsons is great. The show has been a pop culture institution for decades, longer than many viewers who catch re-runs on FXX have been alive. Characters who started out as stereotypes have evolved into archetypes (the Sea Captain character becomes THE Sea Captain character.) Entertainment Weekly named the series the best tv show of the 1990s. Time magazine named The Simpsons the 20th century’s best television series. An authority no less than Nathan Rabin called The Simpsons “the foremost pop-culture achievement of the 20th century, and the greatest television show of all time.” Currently in it’s 27th Season and sitting at 575+ episodes, the animated sitcom is America’s longest running scripted television series, with future seasons already on the docket. The show that started as a skewed take on the American Family Sitcom quickly broadened into an all encompassing satire of nearly every aspect of American Culture; family, politics, education, religion, law & order, business, romance, marriage, entertainment, childhood, growing old, health, recreation, down to the little day-to-day slices that make up this American life. If Seinfeld is a show about “nothing”, The Simpsons is a show about everything; I’ve often joked that if a something is truly worthwhile, there is a Simpsons reference to accompany it.

As a pop-culture kid, who was 8 (and a half!) when The Simpsons premiered in December of 1989, it seemed to be a full blown cultural event, with the show gracing everything from Elementary playground conversations to pronouncements from the Leader of the Free World. It’s much too intimidating a mission to gauge the show’s cultural impact on the whole but I can say for sure that, besting The Far Side cartoons and A&E: An Evening At The Improv, there is no other piece of pop culture that has shaped my sense of humor more than The Simpsons. The show’s whip-smart take on American life during it’s nearly undisputed Classic Years coincided with my coming of age as a wide-eyed tweenager. At that age you are (I was) trying to make sense of the world armed with an array of seemingly contradictory impulses and no other show seemed to recognize and capture those day-to-day contradictions so well (look no further than the way the show lovingly prodded or bitterly critiqued religion over the years, sometimes doing both simultaneously.) They approached every topic with a knowing sense of humor, which felt somewhat grounding to me; if something was lightheartedly ephemeral, deadly serious or confusingly hypocritical, at least you could laugh at it. The show felt like it had a stance on the world and maybe my favorite thing about the show is the way it filtered that stance through pop culture references.

I’ve always been interested in the way that pop culture impacts people’s everyday lives; as shared experiences, as touch-points to contextualize a moment, as morality plays or cautionary tales, as validation when you see a shared thought or feeling articulated, as a touchingly pathetic companion or as a means to find common ground through an appreciated reference. I know from personal experience that pop culture, in the form of TV, movies, books and music, can be really important to people and can be used to process the world around you and I love the way that The Simpsons approaches that dynamic. Pop culture references as jokes has been around even before Looney Tunes cartoons were goofing on old Hollywood, but what sets the Simpsons apart from contemporaries like Family Guy (recognition/re-creation as joke) or South Park (references as hot take fodder) is the way the show uses pop culture reference to influence understanding of character, theme or story.

At its best, the show uses the intertextuality of references to create something new. Characters filter their experiences through pop culture, which, as viewers, shapes our understanding of their stories. Creators see the world through a pop cultural prism, so characters and the show’s perspective does too. This is the same approach Quentin Tarantino uses in his movies, defining characters through their pop-culture obsessions and bouncing disparate cinematic elements against each to create something unique. This is Wu Tang Clan framing their day-to-day New York narratives and larger-than-life hip-hop personas with martial arts films and Marvel Comics lore. This is Simon Pegg and Jessica Hynes in Spaced, using One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest to illustrate the experience of working a restaurant kitchen. This is Edgar Wright using zombies, cop movies and sci-fi to explore questions of coming of age, friendship and homecomings, or being drawn to the way Bryan O’Malley’s graphic novels filtered Scott Pilgrim’s life through his understanding of video games. This is the team behind LOST packing their show to the gills with literary allusions or Dan Harmon using genre tropes to reveal human connection and genuine emotion in Community. For The Simpsons and it’s ilk, references and pop culture allusions aren’t an end unto themselves, they are a means to articulate something bigger.

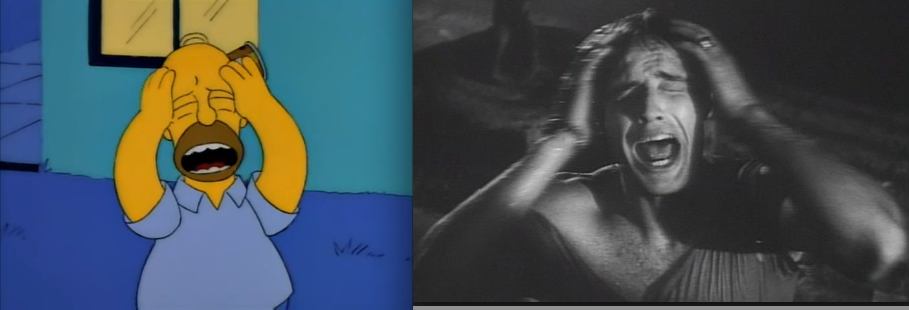

The second episode of The Simpsons‘ fourth season, “A Streetcar Named Marge” is a great example of how wide ranging the show’s satirical targets had become (topics touched-on aren’t limited to, Beauty Pageants, Celebrity Fashion Commentators, Community Theater, the Child Care Industrial Complex, Literary Adaptation, and Broadway) and it’s also an excellent example of the way the show approached pop-culture-references with a similar variety. There are jokes that revolve around celebrity perfumes (“Meryl Streep’s Versatility“), TV dinners and the philosophies of Ayn Rand but there are several cleverly specific sight gags and visual allusions to classic cinema, too. The episode finds Marge auditioning for the role of Blanche DuBois in a local musical adaptation of A Streetcar Named Desire (“Oh, Streetcar!”) and the episode plays around with the ways that Marge’s life with Homer has prepared her to portray, as Jon Lovitz’ theater director sees Blanche, “a delicate flower being trampled by an uncouth lout”. The show weaves references to Tennessee Williams’ domestic drama throughout the episode and visually references Marlon Brando in Elias Kazan’s film adaptation, setting up the impression of Homer as Stanley.

With rehearsals and the demands of the play taking up more of Marge’s time, Maggie needs to be put in daycare, with Marge settling for the Ayn Rand School for Tots, “the only daycare center in town that’s not currently under investigation by the state.” They take a bit of a tougher stance towards early childhood development (“Mrs. Simpson, do you know what a baby’s saying when she reaches for a bottle?… She’s saying, “I am a leech.” Our aim here is to develop the bottle within”) and end up confiscating Maggie’s pacifier, setting the stage for an extended prison-break sequence riffing on The Great Escape, complete with iconic Elmer Berstein score and establishing Maggie as the rebelliously irreverent toddler equivalent of Virgil Hilts.

Maggie’s daycare rebellion sees success in neutralizing the head-mistress and reuniting the baby inmates with their paci’s. And pacify they do; when Homer, Bart and Lisa come to pick up Maggie in route to opening night of “Oh, Streetcar!”, they step into the disquieting scene of a sea of babies just biding their time… (framed as an homage to The Birds.)

Where the first two screenshots use a pop culture allusion for characterization, this one uses the allusion to establish the tone of a story beat; it’s a literal portrayal of a reaction like, “It was so creepy…it was like something out of a Hitchcock movie”, showing the dynamic rather than telling and letting the textual associations color in the scene. The Simpsons would often let these types of allusions pass by indirectly, establishing a connection without calling too much attention to itself. In this instance, though, the writing staff must have been feeling pretty pleased with the reference because they underline it when they tag the scene with a direct recreation of Hitch’s cameo in The Birds.

As the play gets underway (SIDE BAR: there is a whole separate essay to be written breaking down how brilliant the “Oh, Streecar!” sequences are; from the Sweeney Todd-esque opening about New Orleans (which inspired some real life protest from the Crescent City), Jon Lovitz’ brilliant turn as the theater director (I can’t listen to someone talk about their past experiences with amateur drama without think how the review “Play Enjoyed By All” speaks for itself), the laser-show-aided representation of Blanche’s “decent into madness”, the misguided intention of the song adaptation of the play’s final lines, etc.), the distance between Marge’s ambition and Homer’s ambivalence seemingly comes to a head, with Homer’s apparent boredom being illustrated with a nod to Citizen Kane and theater critic Leland’s boredom toward Susan’s opera performance.

As she receives rapturous applause at the curtain call, Marge sees Homer in the crowd, looking distant and dejected. Marge’s successful attempt to pursue an interest outside of the family seems to be swept aside by Homer’s inability to see what she really wanted to get from the experience; her husband to respect her efforts. From Marge’s vantage point of the stage, Homer seems to be all too much the Stanley stand-in, crude and unthoughtful, too stubborn to see the impact his brutishness has on those closest to him. But given the chance to explain his reaction to the play, Homer reveals himself to be a bit more thoughtful than expected.

Homer: …Marge, you were terrific.

Marge: Oh, come on, Homer. By the end, you were so bored you could barely keep your selfish head up.

Homer: I wasn’t bored. I was sad. It really got to me how that lady, uh, um … you know which one I mean. You played her.

Marge: Blanche.

Homer: Yeah. How Blanche was sad, and how that guy Stanley should have been nice to her.

Marge: Yeah? Go on.

Homer: I mean, it made me feel bad. The poor thing ends up being hauled to the nuthouse when all she needed was for that big slob to show her some respect. Well, at least that’s what I thought. I have a history of missing the point of stuff like this…

Marge: No, Homer, you got it just right.

In the end, is was Homer’s ability to absorb a lesson from the play that reminded Marge that his thoughtlessness isn’t malicious and deep down he understands her motives and feelings (even if he’s not quite able to make that connection himself.) It was honestly interacting with a piece of popular entertainment and filtering it’s meaning through their own experience that saved the Simpson’s marriage (this week!) and I think it’s a nice illustration of the way pop culture can influence people’s daily experiences. I know that I do the same type of thing in my life and I appreciate a pieces of entertainment that reflect that. Seeing The Simpsons approach their storytelling so cleverly, casting such a wide-cultural-net and with such deliberate intention, it makes me feel like looking for a deeper meaning in pop culture of all kinds, engaging with works on their own terms and unashamedly treating pop culture as culture isn’t a fools errand, it’s a perfectly cromulent pursuit.