“You brought this on yourself.”

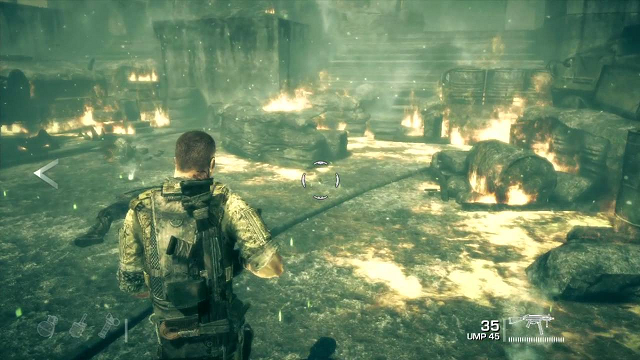

That’s a line that recurs all throughout Spec Ops: The Line – the 2012 third-person shooter from Yager Entertainment – and is deeply tied into its morality and what it has to say. Multiple villains say it, and the protagonist says it at least twice. The main theme of the game is the terrible things a person can justify doing under the notion that they’re the hero; it connects this with both American interference in the Middle East (the protagonist, Walker, quite literally being an American military officer in the Middle East) and with the logic of action video games at the time. The most infamous part of SO:TL is when Walker calls down white phosphorus upon an area in a sequence which would be hard to watch even without the innocent civilians caught in the blasts; I find myself just as struck by the fact that he inadvertently dooms thousands of people to death by dehydration when he botches transporting a truck full of water. From the start, this is all driven by Walker trying to play the hero against all warnings; one of the most powerful tricks in the game is that Walker was only sent for observation and chose to break orders and interfere in the first ten minutes of the game.

“You brought this on yourself,” is his justification. Outside of my esteemed colleagues, I have often found that when people say ‘actions have consequences’, what they mean is ‘this action should have this specific consequence’. People need to learn that when you do one thing, it triggers a specific response, these people say. George Orwell characterised this kind of thing as a belief in Law as an immutable force of nature as opposed to a thing people do to one another; the people of my particular subculture refer to it as ‘fuck around and find out’. There are two downsides to this attitude. The first is that it causes unbelievable angst when the appropriate action does not create the appropriate response. There’s a phrase that’s become popular to describe men who are nice to women under the pretext of sex – “girls are not vending machines where you put nice coins in and sex comes out” or something like that. I think there are a lot of people who recognise this behaviour in others but fail to see how it transfers to their own mistakes.

More importantly, it ironically minimises responsibility. The premise of the story is that Walker’s former commander, Konrad, has gone rogue and made himself king of sandstruck Dubai; the big twist is that Konrad had been dead since before the game started, and Walker has been hallucinating radio messages from him; the central insight is that Walker had to literally invent a villain, first to justify his hero fantasies, then to rationalise his increasingly deranged actions and their bloody consequences. Order Of The Stick fans would recognise a lot of Redcloak’s story in Walker’s; Walker and Redcloak’s story isn’t of a single action and all its consequences, but of making the same decision over and over and over and watching the bodies pile up and convincing themselves it’ll all be worth if they could just succeed at this goal whilst ignoring the goal they’re actually chasing.

It’s a cheap comfort to attribute the things to you do to God or the universe or an abstract sense of right and wrong; I am often puzzled by atheists who believe there is no God, no divine entity running the show, and yet still have a full quasi-religious sense of Good and Evil as if they’re inherent qualities of the universe (as opposed to words people give to emotions they feel), but I suppose that’s just a thing most people do. There’s a phrase I’ve seen used, “Main Character Syndrome”, to describe people who act as if they are the ones who exist to pass down moral and practical insight into the world and whose decisions are the only ones that matter. It’s fun to diagnose people this way, but I don’t think it generally captures the mindset of people who act like that.

Rather, I think people who act like this are the exact opposite – they don’t fully recognise what they do as decisions. It’s an impulsive jumping to the first action that jumps into one’s head as opposed to a reasoned commitment to a goal or philosophy or even feeling. “You brought this on yourself” is even worse, though; it’s faux-commitment, self-righteously castigating someone for evading responsibility whilst being its own form of evasion. As with a lot of things, I find myself thinking of The Shield. Firstly, I think of Claudette, evolving into perhaps the best model for how a moral absolutist should live. It’s not that she doesn’t judge people, it’s that she doesn’t let her sense of good and evil get in the way of doing the right thing. I think of her telling Julian about her plan to move in on Vic, knowing he’s on the Strike Team and might not want to be a part of the plan against him. She knows what is and isn’t her decision to make.

Secondly, I think of a line that does not appear on The Shield. The wonderful thing about the show having a powerful dramatic engine and wildly inconsistent dialogue is that you often end up cleaning up the dialogue in your head, usually but not always to make it more beautiful. In the final episode, there’s a line Vic says to Ronnie that I misremembered as “I’m sorry! I thought I had to make a choice!”. This, of course, is me not just reshaping the dialogue to fit my standard of beauty but my morality. There would be something satisfying in Vic actively taking responsibility for prioritising one thing over another, no matter how much it hurt him. It’s cool to think of yourself as a Nemesis or a righteous deliverer of justice or He Who Gets Results or a Cowboy Cop or some other magical icon, but there’s something soul-cleansing in thinking of yourself as a human being who made a decision and lived with it.