Of course, 1958’s Cat on a Hot Tin Roof was forever fated to linger under the shadow of that other seminal 1950s Tennessee Williams adaptation, A Streetcar Named Desire — the movie that showed us the importance of relying on the kindness of strangers, and introducing the world to Marlon Brando, and his torso that launched a thousand ships. Yet Richard Brooks’s film version of Cat on a Hot Tin Roof should not be overlooked. In much of theme and setting the two works are similar, but the differences are apparent, and telling.

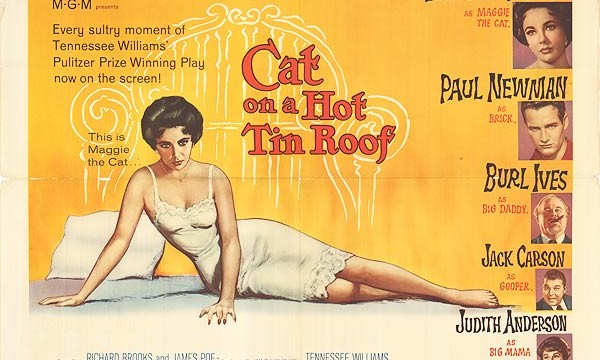

But first the plot: on an expansive and expensive cotton plantation in the Mississippi Delta, the small but wealthy Pollitt family reunites to celebrate the 65th birthday of family patriarch Big Daddy (Burl Ives), fresh out of a rest clinic with a clean bill of health. Son Brick Pollitt (Paul Newman), an ex-college football hero who has bottomed out and turned to drink, hardly interacts with his family, spending all of his time drinking in his room, ignoring his feisty wife Maggie (Elizabeth Taylor), who tries, vainly to get any kind of spark from her husband. The bottled-up tensions of the family come to boil when Brick learns from Big Daddy’s doctor that the old man is not, in fact, healthy, but is unknowingly dying from a malignant tumor. The cunning, “poor all my life” Maggie aims to outmaneuver Brick’s older brother Gooper and his scheming wife Mae before they can trick Big Daddy into leaving them the greatest share of the inheritance.

All the while, these characters tiptoe around their problems, mostly afraid to talk about what it is that is tearing them apart or wedging them away from their family members. “Mendacity” — that is to say, deception — as Brick spits out time and time again, is the name of the game. While A Streetcar Named Desire also chiefly concerns itself with the lies and illusions that people erect to keep themselves from dealing with aching truths, for most of the story, this “mendacity” is mostly centered around the quite obviously delusional character of Blanche. But in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, whose title refers to the passionate Maggie feeling as though she is trapped atop a burning surface with nowhere to turn, the mendacity is clearly endemic to the environment, whether it be the Pollitt family, polite Southern society, or humanity in general.

This is all in the Williams play, though, and perhaps we should now concern ourselves with what director Brooks does with the storytelling. All-in-all, the film lacks the precise charm and repugnance of Elia Kazan’s earlier Streetcar, with its murky phantasms of paper lanterns, its caterwauling street vendors, and its waterfalls of hot sweat and cold rain. There is a dubious decision at the start of the film, to begin with a scene of Newman’s Brick boozily trespassing on his old high school athletic field, imagining a roaring crowd (complete with cheering noises on the soundtrack), and breaking his leg while trying to run the hurdles. It is almost entirely the wrong choice, edging too far into expressionistic POVs that the film will not indulge in again, breaking too far from the closed-off setting of the plantation, and showing something that is more than adequately conveyed by dialogue throughout the rest of the picture. And although the film is fine to look at, well-photographed by William Daniels, it doesn’t do too much with the Technicolor palette.*

*In fact, there is one scene, with Paul Newman and Burl Ives a basement during a rainstorm, when the reflections of raindrops sliding off a window appear on Ives, but the color cinematography makes the effect too subtle to leave an impact. Director Richard Brooks will later utilize this effect with much greater panache and significance in 1967’s In Cold Blood — in black & white.

But Brooks does some things quite well. First among them is that he knew how to cast the right actors and let them act, dammit. Even though the two lead roles of Brick and Maggie have been filled by two big-name Hollywood stars rather than their Broadway originators, potentially a bad sign, Taylor and especially Newman acquit themselves by giving performances that should make any actor proud. Brooks also smartly shoots these two beautiful Tinseltown titans in just the right way to capture their unique qualities. Taylor’s big, envelopingly dark eyes balance Newman’s small piercing blue gems — displaying not just visual harmony/disharmony, but the respective power and acuteness of their characters.

Brooks takes advantage of staginess to create a somewhat stultified atmosphere, where characters will stand in a room, carrying on a conversation, with their backs turned from one another, often in different planes of the frame. It feels like everyone in the Pollitt family is unable to meet the eyes of anyone else, lest they should find out or reveal from themselves an ugly and impolite truth.

Speaking of impolite truths, it is here we reach the inevitable Hays Code section of the review. Brick Pollitt has had an ongoing love affair — perhaps consummated, perhaps not — with his old football teammate Skipper, whose suicide has sent Brick into a liquor-stained tailspin. He is unable to perform for his wife, and his inability to provide his father with grandbabies would perhaps mark him as the “lesser son.” Maggie is horny and frustrated with her husband’s impotence — whether in the bedroom or outside of it. In fact, Brick — apart from the ill-advised opening scene — doesn’t even leave his bedroom until well over 45 minutes into the movie, and doesn’t even speak to anyone other than his wife and, briefly, the doctor in all that time. Newman has to convey his character through remarkable inaction — inability to leave his room, inability to face his wife, inability to speak in the presence of his brother — and does so remarkably well. We tend to think of these Tennessee Williams adaptations as being very heated and passionate, with characters gesticulating and strutting and sweating — and rest assured, there is a lot of sweat in this picture, particularly from Burl Ives, who looks like if Louis C.K. ate Louis C.K. — but Newman has to essentially carry the film on his shoulders while mourning someone we never see and never really know. It’s great work, and an early jewel from one of the greatest leading men in Hollywood history.

Of course, in 1958 an MGM motion picture couldn’t go around and use words like “homosexual,” “gay,” “sodomy,” and so on and so forth, but this stuff is pretty much as textual as one could legally get in those days, and comes off better than the subplot in A Streetcar Named Desire does — y’know, the one about Blanche’s dead gay ex-husband who is still dead, and still ex-, but not really gay.

The film comes to a conclusion, slightly altered from the original stage production, where secrets are let out, truths are revealed, character dynamics are shifted. And most crucially, the systemic mendacity of the whole damn family is re-purposed when Maggie uses a lie that everyone knows is untrue, and no one is willing to acknowledge, yet ends up likely saving her marriage, keeping the family together, and helping more than it hurts. It’s a little too nice and tidy for a story like this. It’s a bit like the tag on the birthday gift that Maggie tries to get Brick to sign against his will; a way of taking the respectable audience, who have sat down to watch a respectable film from MGM, that most respectable of studios, and who have sat through two hours of homosexuality, impotence, malignancy, and, yes, mendacity, and letting them off the hook at the end. But the irony of the reversal of fortune that Maggie has inflicted, or maybe gifted, to the Pollitt family is hard to resist in its lyin’ charm. These twists, those performances, and that crackling Tennessee Williams dialogue makes Cat on a Hot Tin Roof a fine example of fine southern discomfort. The cat revealed her claws, and damn if I didn’t enjoy the scratch. Well, most of it.