THE PROCESS

Before The Campaign

Get the players to give you at least two pieces of backstory: where they were born, and how they got the skillset for their class. Experienced players will generally have a lot more detail than that, but those two pieces of information will give you a minimum shared understanding for their vision for their character, and more importantly plot details that let you fill out the story early on. Look up the d20SRD map generator and use it to generate a world; even if you don’t meticulously go through and work out the individual populations and geography of every single village, town, and city, you can at least form an overall idea of the geopolitical situation (like where the elves and dwarves and humans all are and how they relate to each other). Choose one world-defining thing – something that the geopolitical forces as a whole are reacting to. In one campaign, I have the emergence of a new and powerful magical resource that is, in turn, affecting the behaviours of dragons as it’s being mined (a la whales being affected by sonar); in another, the universe has been fundamentally poisoned somehow, causing the gods to leave (and subsequently return for reasons not yet explained to the players).

Again: this is to serve the plot.

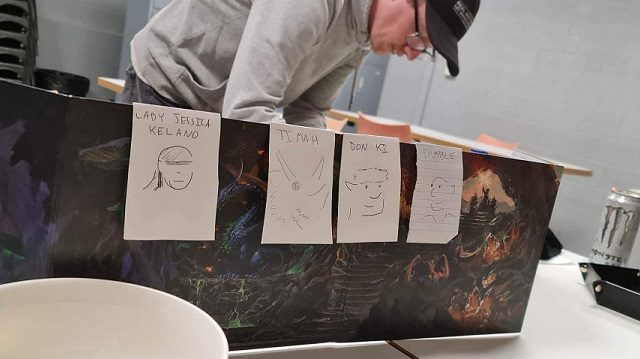

In terms of props, draw up initiative order cards. On the DM’s side, put the character’s passive perception. Make up three playlists on your phone – one to set the mood for battle, one to set the mood for tense travel (e.g. through a dungeon), and one to set the mood for peaceful moments.

Session One

Start the players off in media res. In the opening narration, they have already each individually accepted the same job and formed a team a la The Dirty Dozen or The Suicide Squad. This allows them to view each other as comrades without necessarily having to perform camaraderie (allowing any dynamics between characters to develop organically). As they perform their relatively simple task, throw in a complication to escalate tension – my most effective spin on this idea was sending the players into the drow Underdark to retrieve an artifact, only to interrupt things with the duergar starting a war with the drow. The players will establish their characters, responding to problems as only they would.

Between Sessions

It’s best not to plan too far ahead. Rather, stock up on potential setpieces you can unleash on the players. Get a small folder in which you keep the player’s initiative order cards, your map of the world, and then statblocks for each enemy you plan to use – ideally, photocopied straight out of the Monster Manual or whichever book you’re using. Each monster has a Challenge Rating; CR is infamous for being useless, but in fact if one uses a simple formula, it becomes quite powerful.

(x + 1)y

x = the number of people in the party and y = the party’s individual level. So if you have four party members at level five, the formula is (4 + 1)5, or 25. This is the combined total CR of all the monsters you can use in an individual fight that you intend to be quite challenging but not impossible. So this particular party could face a group of enemies consisting of a Mind Flayer (CR 7), two Flesh Golems (CR 5×2), a Hobgoblin Captain (CR 3), and ten Hobgoblins (CR 0.5×10), and it would be a challenge but you could be confident they’d defeat them.

On top of this, where possible try and have some extra puzzle in a setpiece for the players to solve – one that isn’t necessary to resolve the story or defeat the baddies, but will give them a considerable boost and effectively reward them for investing in non-combat skills. To put it in purely mechanical terms: give each location a set of details that the players will be able to use in a combat situation, and the higher they roll on a specific kind of check, the more information you’ll give them. My first use of this concept was wildly successful: the players stayed at an inn, and any player who cared to make a Religion or Arcana check upon prompting was immediately told they realised the inn would strongly resemble a pentagram when seen from above.

Players who rolled above a 15 were told that it was a human sacrifice ritual. The one player who rolled above a 20 was handed a sheet of paper that said that the inn owner was walking towards a specific table, and that if they were not stopped in the next three turns, everyone would suffer a poisoning effect – not lethal, but definitely debilitating. I then told them to roll initiative and started the fight. This was so successful and so tense and so fun that I learned the obvious lesson: create a bomb with a clock, and the higher the player rolls on a check, the more information they’re given about that bomb. It goes off regardless but they can be prepared.

Once you have both that formula and the general plot in mind, plotting becomes an intuitive and even obvious process. You have to remember that, just by existing, the players have relieved half the burden of storytelling for you – most players have some kind of goal (I have the privilege of a player who frequently comes up with hilariously specific variations on ‘world domination’) and all you have to do is throw things in the way of that. One of my most effective story moments was when I had a player whose character was more of a gimmick than anything – a dad who only saw his kids on the weekends and was adventuring to pay child support. It took me a shockingly long time to click onto the very obvious move of having the bad guys kidnap his kids (which immediately set the player and character in motion), and it was followed up with the slightly more inspired choice to have one of said kids be a Chosen One. Now all I have to do is keep throwing obstacles at the players; ideally obstacles with a time limit (hmm, maybe the Chosen One starts getting a bit sick…).