So, I’ve been DMing a Dungeons & Dragons campaign for a few months now, and as is my wont, I’ve been developing theories of best practice for it. For those who came in late: a Dungeon Master is a combination of storyteller, computer, and referee for a D&D campaign. They do three things: 1) design environments and enemies for the players to engage with, 2) roleplay the nonplayer characters, both in terms of controlling enemies during fights as well as giving voice to people that the players meet, and 3) adjudicate rules. Oddly enough, I’ve found it’s more relaxing than actually being a player. The story I’ve often been told about DMing is that it’s like herding cats – trying to figure out how to manipulate and occasionally force your players into spotting and following up on plot threads so you can tell your epic story. The webcomic Darths & Droids is a very funny expression of this, showing someone constantly trying to keep the players on track for telling his story despite the fact that they keep destroying shit and going down the wrong direction, and almost every strip has advice on how to reward, punish, or tolerate your players for messing up your story. Not only does that not really fit with what I want out of DMing or what I’ve experienced as a DM, I think it fights against the very qualities inherent to D&D.

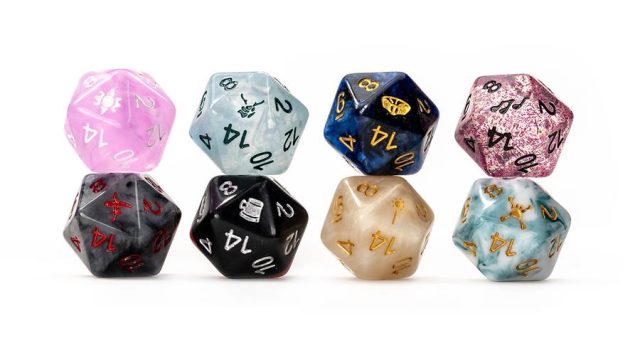

D&D is a deeply systematised experience. It has a simple action at its heart – when you try and do something, you roll a twenty-sided dice (aka a d20) in hopes of beating the score indicating the difficulty of the action – with a system of rules and exceptions that complicate this. Suppose you want to lift a big rock – you roll a d20 and you add your Strength modifier to the result in the hopes that this will compensate for a low roll. This means that D&D is not a formal experience. It’s not the twelve bar blues, in which musicians know exactly what chord is coming and have to react to it; it’s not a performance of Hamlet, in which even the audience knows exactly how the story goes; it’s not the tightly structured games of Whose Line Is It Anyway. The structure is improvised – even the DM can’t control how the dice will roll – and the systems of character design are based around making improvisation as easy as possible. The interesting side effect of this is that D&D has no specific goal to achieve. Systems have no motivation – they’re something that individuals use to achieve their motivations.

The Dungeon Master’s Guide lays out various motivations players will have for playing D&D, some of which I can corroborate with experience. It basically comes down to three things: roleplaying, fighting, and optimisation (which usually but not always fits under fighting). Some players really enjoy creating efficient machines that fit together like a Swiss watch. Others enjoy developing character; I play with a guy who built his character around him being a dimwitted inconsistently-accented comedy character straight out of something like Futurama. Obviously, most people enjoy multiple elements in different ways. I was immediately drawn to character concepts and was averse to optimisation, but found I do enjoy tinkering with how a character works over the process of playing. Like, doing it all in one go at the start is tedious, but a gradual, scientific process of optimisation actually is fun. Conversely, one of the players in my game created an especially intricate character weaving together different technical elements in an efficient way and then focused his attention in the actual game on developing his character’s views and feelings. What’s interesting is that there is no equivalent set of motivations suggested for DMs.

One can reframe the role of the player and DM by the decisions they’re supposed to make. The player decides what abilities and inherent qualities their character has and they decide how their characters react to events. The DM decides what the characters will face in the first place – the people they’ll meet, the places they move through, the creatures they’ll fight. If a DM wants to tell stories, it’s perfectly possible to do so, but they have to accept that while they have control over how that story starts, the players get to decide how that story ends. The thing I have very quickly found is that players are very good at using whatever is given to them to tell the story they actually want to tell, and that this is almost always more interesting than whatever idea I had going anyway. The Darths & Droids assumption is that a DM wants to give their players goals, which can sometimes be true – certainly, when I started playing regularly again, I needed gentle nudging in any direction – but most players know exactly who they are and what they want, and I generally prefer to get out of their way. That is to say, I’m not the storyteller, I’m the audience.

What I’ve found I enjoy most of all about DMing is getting to watch the funny dynamic develop between players and characters. At the moment, the two main characters of my group are: a warlock shard of an Elder God (think like Cthulhu or Azathoth) who essentially fell into this world and is creating a cult dedicated to himself in order to amass enough power to return home – and an elf that was kidnapped and sold as a child, and is now roaming the country to get revenge on the guy who sold her in the first place. There’s also a third player with the more erratic schedule who is playing a pure comedy character – an actor who has been cursed into believing he’s a knight from a story*. Watching the dynamic between these three is a lot of fun; the warlock has effectively become the team leader, because he has goals that require active engagement as opposed to the reactive nature of the other two. The elf has a setup where she’s incredibly, hilariously childish right up until she finds out something about her revenge target, at which point she becomes entirely serious and completely consumed by it. Pop culture point of comparison: the M*A*S*H TV show – first with the jokes, then comes the heavy stuff. These two have ended up forming a rather strange buddy comedy; the warlock has ended up an authority figure, and the elf needs an authority figure to mess with – which, by definition, requires obeying the authority figure from time to time. They have ended up drawn together even moreso because of the larger plot.

*We’ve picked up a fourth player but due to scheduling conflicts we haven’t seen the new dynamic emerge yet.

That’s the surprising element I’ve discovered about DMing – plotting. My first priority was “what is an enemy the party can face this week?”, and my usual solution was to look up a random encounter generator to do the majority of the work for me in calculating the right balance of difficulty, and I would at least go to the effort of justifying it based on where the characters were at that particular moment. I was helped enormously by the characters having such clear goals and aesthetic; my very first blank slate idea was to send them on a lowscale ripoff of Lord Of The Rings, and once that was done, the warlock decided to investigate the town he was in for any occult activity. Being the Lovecraft nerd that I am, I improvised a Lovecraftian scholar, fed him some plot details from “The Colour Out Of Space”, and told him that the answers he was looking for were in a city to the north. After that, it was largely a matter of coming up with a monster o’ the week that they stumbled upon and dealt with; at first, this was simply how I could buy myself time to figure out where I was going with this, but this quickly taught me two things: firstly, just about how much ‘content’ fills up a single session, and more importantly, how easily my players can run away with an idea. The warlock has a few straightforward tactics; for one, he will attempt to brainwash just about any useful enemy he comes across rather than kill them. The elf is much less predictable in action but even more predictable in result in that it will probably end with destruction of something, whether that’s a town or an NPC’s dignity.

Even better, I learned how I could spin anything into being relevant. The big turning point in my approach was when I had about twenty minutes left in a session and the players reminded me there was one more town inbetween where they were and where they were going, and I ended up blurting out that they came across a nunnery. When they investigated, my mind went to Alien and I gave them a simple quest: deliver a sick nun to the city. The party continued on their quest, and in the middle of the night, I had the nun explode and two demons emerge. They fought it, and I had successfully managed to fill time to the end of the session, though I was annoyed with myself for distracting from the main plot. Over the next week, I realised not only could I build a huge setpiece out of this – perhaps this happened to all the nuns, and now the players have to fight a shitload of zombie demon nuns! – I could actually tie it into the main plot by having it be something the elf’s enemy caused to happen. It totally fucking ruled – hilariously, before anything even happened, the warlock came up with a plan to infiltrate the nunnery by impersonating the dead nun, so I had the humour of dramatic irony before events even began combined with being able to drop that plot point earlier than I expected; the idea was that the bad guy had sent the sick nun to the nunnery to see how it would turn out.

Hearing the name of her enemy caused the elf’s ears to prick up, and somehow none of the players caught on that something funny was going on until the elf’s keen senses picked up that there were no animals or birds near the nunnery. The violence that ensued owned hard, and the characters reacted to the information in their own respective ways; the warlock brainwashed the strongest demon to join his cult, and the elf, after absorbing all the information in the nunnery, chose to burn it to the ground. What I learned from this is that all I have to do to advance the ‘main plot’ is drop some information relevant to the quest and the players will run away with it, and I don’t even have to do that for everyone to have a good time. I’ve found DMing makes me feel how I always imagined Damon Lindelof felt writing LOST – figuring out how and when to deploy information for the overall story while developing the plot o’ the week and using that to set characters in motion. At first I came up with NPCs that would be fun to play, like a dragonborn bard playing out an Evil Robin Hood fantasy; surprisingly, he ended up one of the few survivors this party has ever hit, somehow not getting killed but also being considered too weak to brainwash, and so the party let him go.

From there, I’ve escalated into recreating movie plots to see where my players will go with them; I took great pleasure in recreating the Red Harvest/Yojimbo/Fistful Of Dollars plot structure (with a dash of No Country For Old Men to kick things off) and was deeply amused when the warlock sided with the stronger gang, wiped out the lesser, then brainwashed the leader of the strong gang into his cult. Like, even the fact that I twisted the formula by throwing in a third gang wasn’t enough to slow the party down. I would later follow this up with a Magnificent Seven Samurai riff. What I’ve learned – aside from the fact that I’ve seen more movies than that particular friend group – is that what I get out of DMing is all the pleasure of creation and none of the responsibility. I deliberately started with a generic high fantasy world and am getting very amused at watching my players kick it to bits like Jerry Cornelius characters; the fact that the players are expected to triumph over everything I throw at them means I’m not too stressed about winning every fight and can simply enjoy playing with whatever toy I feel like playing with.

I can see how a different person might use the same role to fill a different pleasure. I could see someone creating more elaborate and original worldbuilding that’s fun to explore through, and which hangs together more elegantly (this is essentially what my DM does). I could see someone putting more effort into building difficult and elaborate fights (actually come to think of it, my DM does that too). I could see someone creating their own monsters and aesthetic, using the rules as a jumping off point for an original creation as opposed to lifting everything off-the-shelf the way I do; it occurs to me that in a lot of ways, as a DM, I’m a total hack no better than any mid-90s genre TV writer and that this is a lot of the fun for me. I’m definitely a lot of lackadaisical with the rules than most; I rely heavily on the players I have who remember a lot of the rules better than I do and tend to allow a lot of wacky things through. I could also see DMs who commit much more strongly to a tone; I’ve played with a DM who is essentially a wacky Thomas Pynchon novel come to life (including long musical numbers), and I’ve discussed a horror campaign idea with a friend of mine. This essay was really a place to dump a lot of loose thoughts, so I don’t really have a conclusion to get to here. I suppose it’s that a communal experience relies heavily on individual, clear-headed visions coming together and recognising their visions can only extend as far as one player.