Pearl Jam had one of the strangest careers of any of the major grunge acts in their first five years of existence. Their winding road took them to massive commercial success with debut Ten, an album that as much as any defines the grunge sound in the public memory (thanks to hits like “Alive,” “Even Flow,” “Jeremy,” and “Black”), and then almost immediately to rejecting the rock stardom that found them.

They declined to release any music videos for followup Vs., although that only barely slowed down their commercial success, with its mix of rocking singles– “Animal,” “Dissident,” “Glorified G”– and more acoustic-tinted ballads like “Daughter” and “Elderly Woman Behind the Counter in a Small Town.” (Ten has sold over 13 million copies to date; Vs. 7 million.) They followed that with even more extreme measures, boycotting Ticketmaster and their monopoly on concert venues on their 1994 tour, then releasing as deliberately anti-commercial an album as possible.

Vitalogy‘s title comes from an early 20th-century medical book frontman Eddie Vedder found at a garage sale; the album itself came packaged with a booklet inspired by that medical text, with the lyrics interspersed among photographs, handwritten notes, and literature of very poor and outdated medical advice. The songs themselves, aside from radio hit “Better Man,” ran the gamut from rock that sounded either much less polished than or generally little like the band’s previous work (including excellent rocker “Corduroy”); to strangely experimental, deliberately provocative and anti-commercial oddities, like “Bugs,” an accordion-driven song with Vedder yelping about his bug problem (real or metaphorical, it’s never sure), or “Pry, To,” a song that starts with distant drumming and gradually lets Vedder’s voice come in louder and louder, simply reciting “P-R-I-V-A-C-Y” over and over. (Speaking of the desire for privacy, one wonders if the fate of their Seattle peer Kurt Cobain played a role in their decision to purposely reject stardom.) The album closes with “Hey Foxymophandlemama, That’s Me,” a nominal instrumental overlaid with samples of psychiatric patients talking, from a video recording Vedder made of a news segment when he was 17 (which was 1981, meaning this segment was about Reagan’s slashing of mental health funding and the closure of the hospitals where these patients were staying).

After Vitalogy, which still sold 5 million copies despite their best efforts, the band backed Neil Young on 1995’s Mirror Ball. Two songs the band recorded at the tail end of those sessions didn’t make the album; Pearl Jam later released “I Got Id” and “Long Road” (two of their best, in my opinion) on the EP Merkin Ball.

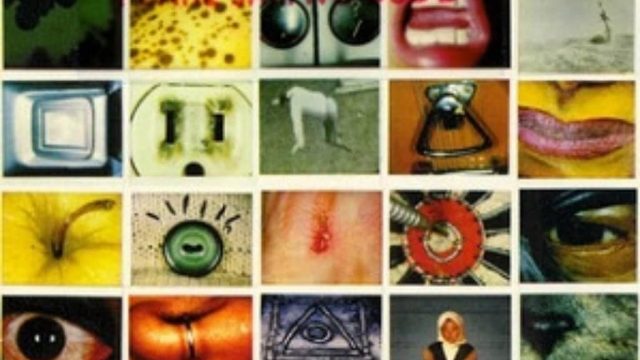

That leads us to No Code, perhaps the best expression of the band’s true self yet, having moved past commercial success and deliberate anti-commercial provocation into just making the music they wanted to make. (Like Vitalogy, No Code comes in its own odd packaging, a sleeved collage of Polaroid photos that unfolds to reveal the eye-in-the-pyramid symbol; the lyrics came printed on the back of nine Polaroids included in the sleeve, one for each song– except that the album has thirteen songs, so you’ll have to buy more than one copy to collect them all.) Leaving both the polished stadium rock and the pissing-off-the-suits novelty tracks behind, Pearl Jam’s fourth album draws its influences much more from garage rock, classic rock and rocker ballads (see the earlier collaboration with Neil Young), and even world music; it’s far more diverse from song to song than the two hit records, and more consistent in quality than Vitalogy.

The two things that tie this album together with yesterday’s Year of the Month (besides being released two weeks apart) are a commonality and a distinction. The commonality is that both Pearl Jam and R.E.M. made deliberately anti-commercial decisions with their records. The distinction is that R.E.M.’s record, written on tour, largely reflects themes of being on the road, on the move, and having no time to rest; Pearl Jam’s album carries much more of a sense of being home, of contemplating the simple yet deep questions, observing the little details of life and imbuing them with meaning. That said, both of them, though from opposite perspectives, express a weariness with fame and the rock-and-roll lifestyle: Michael Stipe’s perspective is of someone still stuck on the road; Eddie Vedder’s is of someone who has already retreated from the scene.

No Code is, I think, childlike (very distinct from childish) in many ways; that is to say, in the sense of innocent wonder that it takes to really contemplate bigger questions about life, in the sincere expressions of emotion that adults can often find blunted by experience and social convention, and in the way insignificant events can take on grand meaning in the mind.

Sometimes that sense is more blunt than others; “In My Tree” sounds like it could literally be sung by a child in a treehouse, although the real theme Eddie Vedder is expressing is his desire to get away from the fame and just have a space to himself, “Just like innocence.” No surprise, really, given that Vedder was dealing with a “pretty serious stalker problem” at the time, a woman who was convinced Vedder was both Jesus and the father (through rape) of her two children.

He takes this incident on more directly in “Lukin”– if you were wondering, that song is named after Vedder’s friend Matt Lukin, bassist for the Melvins and Mudhoney; Vedder would frequently visit Lukin’s home during this time to avoid being at his own, when he felt comfortable leaving the house. (And Lukin’s own influence and friendly razzing of Vedder and rock star excess may explain why the song is a punky 1:02 in length.) And speaking of referencing friends in their music scene, “Smile,” a straightforward, heartfelt expression of friendship and filial love, takes its lyrics from a note Dennis Flemion of the Frogs wrote Vedder (himself taking the words to the note from two of the Frogs’ own songs).

Something like “I’m Open” would’ve been a strange choice for the band before Vitalogy, but on No Code it fits just fine and expresses some of these themes of childlike wonder and attempting to recapture it more directly, as Vedder narrates about a man lying in his bed, contemplating and hoping to feel something:

When he was six he believed that the moon overhead followed him

By nine he had deciphered the illusion, trading magic for fact

No trade-backs

So this is what it’s like to be an adult

If he only knew now what he knew then

That last line is an inversion of the closing hook of “Red Mosquito,” Vedder repeating “If I had known then what I know now.” It’s another song about someone in a room (“Watched from the window, with a red mosquito / I’m not allowed to leave the room”), and of an ordinary experience being imbued with grander significance:

I was bitten

Must have been the devil

He was just paying me

A little visit

Reminding me of his presence

Letting me know

He’s a-waiting

The most blunt lyrics on the album are often delivered in spoken word. In an inversion of “I’m Open”‘s structure, “Present Tense” asks grand philosophical questions sung in the verses (“Are you getting something out of this all encompassing trip?”) before Vedder delivers its chorus message as flat, direct advice:

You can spend your time alone

Re-digesting past regrets, oh

Or you can come to terms and realize

You’re the only one who can’t forgive yourself

Oh, makes much more sense

To live in the present tense

There’s also a Pearl Jam rarity in one of the most rocking songs on the album: A vocal performance, and lyrics, by someone other than Eddie Vedder. Antepenultimate track “Mankind” is entirely written by Stone Gossard and sung by him as well, the first time to date someone other than Vedder wrote Pearl Jam lyrics or took lead. According to Gossard, it was a bit of an attempt to prove he could write and sing a poppy song, which makes the lyrics about “inadvertent imitation” a bit ironic, though most of the song discusses such ideas in the broader context of modern society, disposable lifestyles, patterns imitated because that’s what people do. (I will not use “What’s got the whole world faking?” as an excuse to drop yet another Hypernormalisation-related link.)

The album mixes rockers with quieter tunes; a great example of the latter is “Who You Are,” the lead single from the album, though its energy builds as the song goes, yet another life-affirming tune, touching on life’s wonder and value and especially the value a person has just for being part of it. “Off He Goes” is another quietly contemplative tune, seeming of a piece with the perspective of some of the aforementioned songs; the singer seems to be talking about an old friend he’s always happy to see drop by, but who inevitably has his eye on the road again, ready to leave for whatever comes next, often without warning. (Vedder would later reveal that he really wrote the song about himself.) Closer “Around the Bend” is another quiet, contemplative song, perfect for ending the album; the lyrics seem to be Vedder expressing to a loved one regrets for missing so much time together while on the road and promises to be there in the future. A fine way to end the album, looking to the future with hope for what comes next.

It is my favorite Pearl Jam album in large part because of when it came into my life and what it spoke to me then: I don’t know if it was just being 15 or something else, but a substantial number of my favorite albums I still carry with me to this day were released in 1996. That said, when you consider their early phenomenal success, the stress the band felt from being rock stars, and their conscious attempt to abandon that lifestyle, I also think– and this is why I chose the titular quote I did– there’s a good case to be made that No Code is the album where Pearl Jam really grew up, where they became the band they always wanted to be.