“A notice you hear somewhere might change your whole life,” the teacher tells his class before relaying the Thought for the Day from the paper bulletin in his hand. “’Life is cause and effect. One creates his tomorrow at every moment by his motives, thoughts and deeds today.’”

So begins High School. This is the second of several observational documentaries by Frederick Wiseman who used the advantages of lighter film and sound technologies to record fly-on-the-wall scenes in America’s institutions. The observational veneer means that many scenes of pithy life advice fly by for us, the incidental audience, just as much as they do for the film’s students, the intended audience. It’s only after an accumulation of these scenes that we begin to glean a pattern and only when Wiseman cuts to black at the end that this pattern coalesces into a meaning.

Philadelphia’s Northeast High School, like all high schools, is a ripe setting for the vérité style with its constant procession of small dramas. Observational documentaries avoid intrusion, though it would be more accurate to say they hide their intrusion, keeping it off frame like the microphones and camera operators. Interference is inevitable –nobody is unaware that a 16mm camera and a Nagra sound recorder are running in the room and everybody adjusts their performances accordingly. We’re not seeing a record of candid human behavior in these scenarios but we are seeing people act according to the expectations on their behavior.

We see a few different ideas of what a teacher looks like. One English instructor barrels through “Casey at the Bat” aloud. Another reads the lyrics to Simon and Garfunkel’s “The Dangling Conversation,” asks the students to reflect on its poetic devices, then plays the song on the classroom’s turntable. The Paul Simon words stick longer, with the music carrying over the next scenes.

Another teacher, sporting a military crew cut, features in three separate vignettes. He argues with a student who is reluctant (or unable) to change for gym. The teacher points his pen provocatively and hands out a suspension like an angry dad wielding a belt buckle. He debates another student over not whether his detention is deserved, but what the situation actually represents. He convinces the student to take the detention to demonstrate his character (the student emphasizes he will do so under protest). Finally, Mr. Crewcut takes a down a contrite student who threw the first punch against a smaller boy. “I don’t like the ‘sir’ business,” says the teacher when the fighter tries politeness. “It isn’t sincere.”

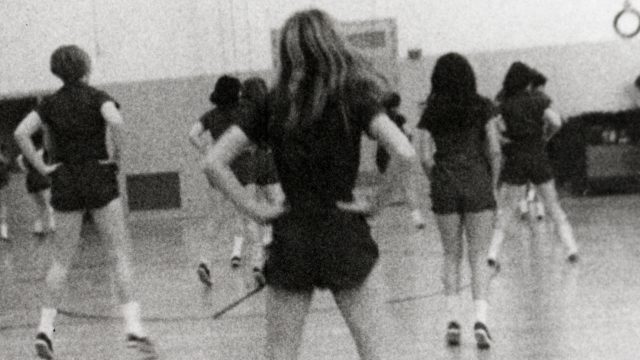

The students rarely feature as the scene’s subject except when trying to explain themselves to adults. By the time we reach an extended shot of gym class calisthenics in drab uniforms set to the bubble-gum pop song “Simon Says,” each new vignette becomes a new attempt by the teachers to get these students in line before the real world outside gets them.

During a rehearsal for a design and fashion show the girls are taught how to walk in the clothes they designed and sewed (this scene gets uncomfortable when one girl is singled out with “a weight problem, she knows it”). There’s an extended conversation about the length of a skirt and what constitutes “above the knee” (turns out the knee is not above nor below itself). While individualism is a good trait, the teen is told, there’s no excuse for not wearing the proper attire to prom, (up to and including not being able to afford it). “I have to wear a long gown,” a teacher explains, “and I can’t walk in it!”

And such is the tenuous reasoning behind much of the enforcement of the rules – it’s a gift between generations. Respect and conformity are heirlooms bestowed with pride. One mother, her fingers nervously picking at her handbag in close up, agrees with the teacher disciplining her student. “Main thing is respect for adults. I was brought up that way, my husband was brought up that way.” In the two-shot we contrast her composure with her daughter’s contorted expression. The mother is someone who has internalized society’s expectations. The daughter is learning how and grappling with why.

The extra-curricular element to everything is the presence of 1968 America outside the school’s walls. Lest it seem like Northeast High School is completely resistant to the social changes washing over the nation, it should be noted that the sex education includes discussions of birth control pills and the abstinence message has been watered down to an anti-promiscuity message. The three students whose college futures are discussed on camera are all girls. One shown with her parents appears to be half-Latina.

This student aside, the school overall appears to contain few minorities. The school’s attitudes on race are defended by a teacher but derided by a black student who says “morally, socially this school is a garbage can” and bemoans the need to “conform” to the school’s ideals (Teacher: “I don’t think it’s that bad”). Another teacher surveys his class for a social experiment, asking how many would join a club if half of its members were black. After some looking around at their peers, the clear majority raises its hands. At least one visible student raises his hand to say he would not. “There are no right or wrong answers here,” says the teacher, “Just trying to determine what attitudes are.”

The war in Viet Nam is barely visible inside the classrooms, relegated mostly to current-event collages on the wall. In the only scene filmed outside the walls of the school, a coach talks with a visiting former student while current students play basketball in the background. The former student is on leave from the military. They discuss another alum who nearly lost his foot in battle. “He was pretty melancholy-like, you know,” says the coach. “But I think he’s got himself adjusted now. He’s going to be all right. Glad you didn’t get hit.”

High School assembles its observations as a series of opportunities for one generation to recreate itself in the next one. The teachers confidently assure the students that embracing the status quo will lead to not just a better society, but to their own success. Wiseman only editorializes with editing and so the closest he gets to making explicit commentary on this is his ending.

The film finishes with another teacher reading another missive. We only see her but it’s clear she’s addressing a student assembly as she reads a letter from a former student on the verge of deployment to Viet Nam. This student, we’re told, was brought up without parents but “a few teachers who cared” made a great influence on his life. Now he writes while he waits to be dropped behind enemy lines to tell them his life insurance payout will go toward a scholarship if he is killed in action. “Maybe it can somebody some good,” he says. He asks for nobody to worry about him: “I am only a body doing a job.”

The teacher works to keep her composure “When you get a letter like this, to me it means, we are very successful at Northeast High School. I think you will agree with me.”

Smash cut to black.