Studio Ghibli’s latest film, When Marnie Was There, feels fitting for a farewell to an era. Long-time producer Toshio Suzuki, who had his hands on every Ghibli film since 1991, announced he was retiring from the producer role to be a Ghibli General Manager. Since first producing Isao Takahata’s Only Yesterday, Suzuki has produced all of Miyazaki’s films, and all of the non-Miyazaki films. His presence in the studio is probably underrepresented in the strength and consistency of the studio.

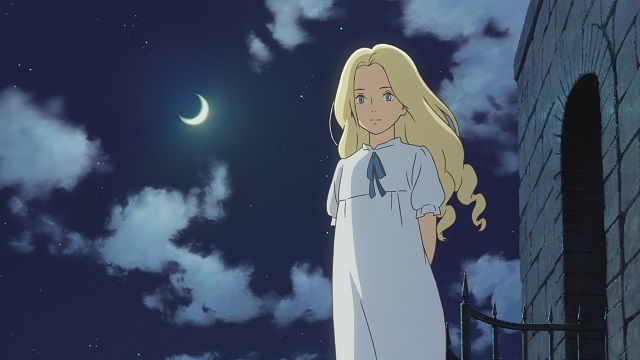

Hiromasa Yonebayashi’s When Marnie Was There deals with issues surrounding loss and identity. 12-year-old Anna is a lonely artistic outcast with asthma who is sent from the city to live with her adoptive parents’ siblings in the country town of Kushiro. Feeling similarly out of place, she becomes obsessed with a mansion across the marsh where she encounters the ghost of the mansion, a girl named Marnie. In order to sort out her own identity, Anna must figure out the mystery of Marnie, leading to revelations of love, loss, and abandonment.

What makes this screening so very special is that SIFF placed this film on Capitol Hill, a neighborhood in Seattle going through its own identity crisis as it transforms from an alt-culture gayborhood to a techster homeland. Marnie screened at the Egyptian theater, a theater that was abandoned by Landmark in 2013, and leased to SIFF in 2014. SIFF’s other Capitol Hill venue is the Harvard Exit, in its last hurrah as another large theater with a balcony. The Harvard Exit was recently sold by the owners to developers who kicked Landmark out, and is turning the venue into a restaurant and offices. Marnie‘s themes of identity, change, and loss are practically playing out in the neighborhood as the ghosts of the theaters will haunt the venues for years to come (also, the Harvard Exit is actually a haunted theater if you believe in that kind of thing).

Following Marnie was supposed to be a screening of The Red Shoes, my first experience with it. I got to see about 40 minutes of the gorgeous restoration on a 35mm print struck from the 2009 digital restoration, but sadly the projector stopped cooperating. Blah. It was a relatively enjoyable movie that seems to have inspired movies for decades from All That Jazz and Fame to Lisztomania. It was gorgeous on the big screen though.

I had my first walkout with Those People, a gay movie about neurotic gay adults doing gay things that seems like it should be from the early 90s or the early 00s. Charlie, a rich trust-fund gay painter, is obsessed with Sebastian, a financial exec of some kind embroiled in a scandal or something. Sebastian is obsessed with himself, even throwing faux suicide attempts and locking himself in bathrooms at parties. For some reason, Charlie and Sebastian move in together, but don’t fuck. Charlie’s friends set him up on a blind date with a swarthy classical pianist, Tim, and they have chemistry. But, Sebastian gets jealous and…fuck it. That’s as far as I got.

I mean, who the fuck gives a shit? Charlie is played by Chris Conroy, who possesses that classic All American innocent boy look that Russell Tovey has in Looking. He’s lusting after an Ian Somerfeld-in-The Rules of Attraction skinny selfish asshole. And, Charlie then hooks up with a swarthy dark and hairy Lebanese guy, Haaz Sleiman. And, it’s all so needy and selfish. It’s like reading a Bret Easton Ellis novel without the irony. It’s like Larry Kramer’s Faggots without the pointed judgement. Fuck these fucking assholes. They should all be taken out and shot.

The movie is absolutely gorgeous in a classic twee kind of way that resembles Duncan Roy’s AKA. The film is lush and full of deep color contrasts to give it a rich palette that aims for a certain classic look and feel. It is separated into months, in a self-consciously Wes Anderson-y way, only without any of the insight of a Wes Anderson film. In a way, Those People is a movie made by its own characters, in that its a gay movie without any sense of self-awareness. I’m far too cynical for a movie about unrequited love with selfish assholes.

This was followed by J. Davis’ Manson Family Vacation, a mumblecore-esque dark-esque comedy-esque that is also a drama about family relations, adoption, and feeling like an outcast. Jay Duplass stars as Nick, a family man who recently lost his father. Soon after not showing up at their father’s funeral, Nick’s vagabond adopted brother, Conrad, shows up to bond before he starts working at a job for an environmental activist group. As a bonding exercise, Conrad wants to explore the locations where the Manson Family made their splashiest headlines.

Thematically, Manson Family Vacation works as a companion piece to When Marnie Was There. Both Anna and Conrad are adopted outcasts who never knew their parents and have to travel to foreign locations in order to find themselves. Where Anna is surrounded by worrying adults, Conrad was constantly judged by his adoptive father further increasing his feeling as an outcast. His search for himself and his sense of family is haunted by ghosts of the past.

But, J. Davis and Jay Duplass never allow Manson Family Vacation to go where it needs to go. It never fully confronts the horror of the past, even on a darkly comic level. The movie’s twists feel natural, but never really poke through with the horror we’re supposed to feel, especially with a provocative title like Manson Family Vacation. It’s mumblecore-lite, but Vacation never finds its identity as either a family drama or a dark comedy. It just sort of exists in a state caught between two or three different tonalities it never fully commits to. (end note: J. Davis and Linas Phillips (Conrad) showed up to talk about the movie, and J. Davis’ real life obsession with Charlie Manson).

Elsewhere, Francois Ozon’s new film, The New Girlfriend feels like Ozon is cribbing from Pedro Almodovar. Cribbing isn’t anything new for Francois Ozon, as many of his films feel like satirical biting takes on various other genres. Swimming Pool was a tongue-in-cheek take on the steamy erotic thriller, and 8 Women takes on women’s pictures, Agatha Christie, and musicals. So, The New Girlfriend taking on Almodovar isn’t so much of a stretch. But, Almodovar is already his own slightly satirical take on women’s pictures using Hitchcockian techniques. Thus, Ozon doesn’t have much room to work with.

In the opening sequence, Ozon establishes the long-term friendship of Laura and Claire from tween years through marriage and childbirth, and ending with Laura’s very premature illness and death. Laura’s too young death leaves her husband David to deal with grief and parenthood, as they had a very newborn baby who is still breastfeeding. Claire, dealing with her own grief, looks in on David only to find him dressing as Laura. Now, Claire and David have to deal with the knowledge that David is somewhere on the trans* spectrum.

Ozon’s take on gender has generally been considered progressive and problematic, a duality reflected in powerful women who seem dedicated to men. This split attitude now extends to trans issues, as the subtitles constantly use the term Tranny, and the Almodovar-lite story line conflates gender issues with trauma and mental illness. That said, Ozon nails two things: a dynamite club scene that rival’s Lynch’s Club Silencio for poignancy, and the finale. The rest is a hugely mixed bag that depends on how much you like Almodovar and Ozon, and also how well you deal with trans* issues.

To close out Saturday, the second Midnight Adrenaline was the Irish horror movie The Hallow. A family moves in to a house in the middle of the woods. The husband takes their baby out with him while he marks a whole bunch of trees for cutting down. I can’t tell if the cutting down is for forest health reasons or for industrial reasons (it seems like it might be both). While in the forest, his soul is marked as a hallow soul. Soon enough the fairies, pixies and goblins are stalking him and his family.

The Hallow had potential to be a Pan’s Labyrinth flight of fantasy, but it reduces itself to a Cabin in the Woods genre bore. It has a Harbinger of Doom in the form of a creepy neighbor who handily delivers the Irish Book of Fairy Tales That Isn’t The Necronomicon But Looks Like It Was In Evil Dead. The family handily traps themselves in a very isolated house far away from any other farm house. The father figure constantly makes the worst possible decisions at almost every possible moment. And, director Colin Hardy is overly dependent on deafening sound cues for jump scares, starting within the first 15 minutes. The mythology is underdeveloped, the rules constantly change, and the characters are barely existent. But, it is a beautiful film. Just a terrible one as well.

Next Entry: Genre exercises, foreign politics, and female sexuality