Because this is a story as much about my own feelings as about The Shepherd’s Crown, I will be unable to discuss it without spoilers. If you don’t want to know yet, don’t read this until you’ve read the book.

The first Discworld novel I ever read was Mort. It’s a fine place to start, one where I’ve started a friend or two myself, in days past. Doubtless I will start friends there in days to come. It was perhaps 1993, and I checked it out of my high school library at the suggestion of my first boyfriend. I loved it. I don’t love all the others; there are four of which I’m not enormously fond. (The first three and Jingo.) I didn’t care for The Long Earth and haven’t read the sequels, and The Carpet People, Strata, and The Dark Side of the Sun are not my favourites, but I love pretty well everything else of his that I’ve ever read, and I’ve read almost all of it.

Including, today, his last novel, The Shepherd’s Crown. And when I finished, I wept, because he is lost now. In closing that book, I have said my last farewell to a man whose work I have anticipated with joy my entire adult life. There is no more; there will be no more. I will be able to catch up on the various Discworld diaries, as I can find them, and there’s still a few other bits and pieces—the fourth Science of Discworld, and a few of the other spin-off books—but there will never be another novel.

Tiffany Aching is the Hag o’ the Hills. The Chalk is in her bones. It is a great deal of work, and she does not have the time she’d like to listen to the land. But one day, when she does, it tells her that something is coming, and she will have to be prepared. Jeannie, the kelda of the Nac Mac Feegle, meets her there, by the stones, and tells her that a time of change is coming.

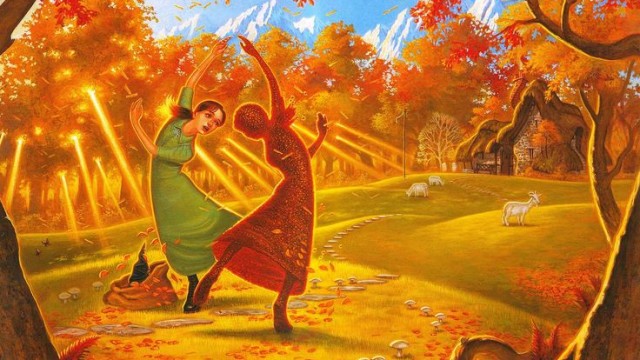

Oh, and it is, it is. In Lancre, Esmeralda Weatherwax cleans her cottage scrupulously. She evicts the spiders from her home, though she allows them to remain in the scullery. She watches her bees dance. She feeds her goats. And she climbs the stairs to her bedroom, lies down on her bed, and is greeted by one of her only friends. A tall man in a robe with a scythe. Not what you’d call fleshy.

And the Disc shifts, and we shift with it. In Slice, Miss Tick feels the shift in a shamble. Across the woods from the cottage, Nanny Ogg nearly drops a jug of cider on Greebo. In Genua, Queen Magrat of Lancre knows that she must return from the royal visit she is taking with her husband. In Quirm, Agnes Nitt knows that she must leave the company with whom she is touring. In Ankh-Morpork, Lord Vetinari considers the balance of power. And Mustrum Ridcully weeps.

All of this by the end of the second chapter, mind. There have been deaths in Discworld before. Lots of them. Death, after all, is arguably the main character of the series. And indeed, I cried years ago when Rincewind was blasted into the Dungeon Dimensions, because perhaps he had died. But this death was more than a death, as I’m sure he thought himself as he wrote it. He’d said once that there would be an enormous outcry if he killed Granny Weatherwax, and he wouldn’t dare do it. She died now because he was himself dying, and that was what would be.

Granny was never one to put herself forward. However, what she did do was stand firm. We learned, long ago, of the standing stones that stood on the boundary between the Discworld and the parasite world that clings to it, the world of the elves. Granny was a large part of the power that kept the elves out. With Granny gone, they see the weakness. Two things stand in their way—Tiffany Aching and the band of iron that is the railway.

It is no longer a time for elves. They alone of the races cannot survive the new world. Humans and dwarves and trolls are just people now, and even goblins aren’t so different, if you can get used to the smell, but there is iron in the world now. Glamour and technology do not get along so well.

There is a wistfulness to the book for what’s lost by losing glamour, for all it’s clear how evil the elves are. An old man in the book wonders how many generations will call foxes Reynard, and I got the feeling that it was Sir Terry’s own wistfulness for some of the lost ways. Wentworth Aching doesn’t want to run Home Farm. He wants to go work on the railroad. But there must be someone to run Home Farm, and Wentworth is the last male Aching. His father is Aching to pass on the family tradition.

At the same time, though, there is a pleasure in change. Jeannie’s oldest daughter doesn’t want to be a kelda and have a husband and babbies; she wants to fight, like her brothers. By the end, we know that she will get her wish, at least for a while. Early in the book, we are introduced to Geoffrey Swivel, the third son of a lord. He wants to be a witch and heads off to Lancre to become one. By the time he gets there, Tiffany has taken over Granny’s steading, and she agrees to train him. Queen Magrat takes up her witchcraft again. And an elf learns empathy. The world changes; not all changes are bad.

This one is. Sir Terry Pratchett is dead, and we are lessened for it. This was not his best book, but it was a closure, at least. There could be worse ones.