As it happens I am still committed to the idea that the ability to think for oneself depends on one’s mastery of the language. . . (“Slouching Towards Bethlehem”)

As it happens. As if it was an aside, something offhand like a change in the weather, as if the commitment was not a matter of choice, just something that “happens,” not even personal, not even from her, from it. As it happens, and what follows is as clear and defining a statement, a commitment, as any author ever wrote. As it happens has a tone of airiness, of triviality even, and committed does not; and the contradiction between the two gives the half-sentence its power, disarming, uncanny. I am committed to this, she says, this is my Credo, but As it happens takes it out of the realm of courage and into that of accident; her commitment becomes an attribute, one more among others, like her slim frame, her shocking eyes. That is what Joan Didion could do with three words. Read her essays, her novels; As it happens there are flips like that on every page, multiple times, the meaning always dancing, always clear, never anyone else’s but her own.

As it happens, she was born and raised in California, in Sacramento, not far from where I’m typing, and like Sam Peckinpah, another great artist of the place, she lived to see the end of an old way of life and the beginning of a new one. She took her beliefs and her prose from a place, as she said, “that placed not much emphasis on why“; a place of floods and fire and earthquakes, where the land was both implacably hostile and a resource to be stripped for parts and profit, where all the judgment in the world won’t get the water to your tap, kill the rattlesnake, make the deal. She knew, as those who saw a world made rather than inherited one, what was necessary and why that mattered more than what was good.

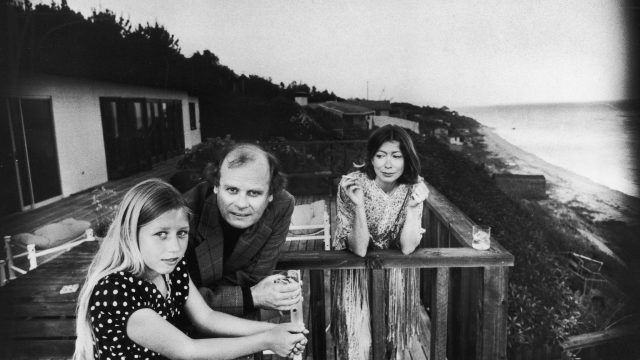

Her grandfather was a geologist and that gave her an array of metaphors, and as she wrote in The Year of Magical Thinking, a faith that others, like her husband and writing partner (I give the two equal emphasis, and so did she) John Gregory Dunne had in religion, a belief in the world without end in which we cannot know. It gave her words and her self a certainty that let her survive nervous breakdowns and family tragedy; a faith that, like George Orwell’s faith in the English people, enabled her to survive as a writer social upheaval and turn it into source material for her art, and her profession. (Didion was Jane Austen clobbered by the 1960s just as Orwell was William Thackeray clobbered by the 1930s.) She understood the fundamental selfishness of the act of creation, and never condemned herself for it, because As it happens, that is what she did, that is who she was.

She was a stone fucking professional as a writer, taking the jobs and getting them done, even legendarily getting called in to write a replacement article at Vogue and not just writing one of her best essays ever, but hitting the exact character count while doing it. She and Dunne made a good living as screenwriters for the film industry, which meant occasionally making a movie but more often revising and polishing the scripts of others, taking meetings, doing the work. When she looked back and decided what she wrote was wrong, she said so; her last two great books were about the two loves of her life, California (Where I Was From) and her family (The Year of Magical Thinking) and they are both revisions of her beliefs, finding the past wasn’t so different from the present, and her style, finding the need to speak clearly, “if only for myself.” She wrote one more book after that, Blue Nights, about the death of her daughter, and it’s both evidence of and lament for the disappearance of her talent: the grace wasn’t there, the voice less confident, the prose more obvious.

It’s cruel to acknowledge that. It’s also necessary.

I learned that from her.

Good-bye, Lady Joan. As it happens, I wouldn’t be this way without you.