So this week brings us another crime. Chapter eleven, “Murder in Dawson Creek: The Comic Books Abroad,” starts with a story I eventually worked out to be set in Canada, though for three pages, I was confused that he kept referring to crown prosecutors and so forth. You see, he mentions at the beginning that the town in question is on the Alaska Highway, but he never mentions that it’s on the section that runs through British Columbia. It’s a small but important detail. Of course, those are frequently the ones Wertham leaves out.

Our story this week starts with two boys playing highwayman on the Alaska Highway. They tried to get one car to stand and deliver, and nothing happened. A second? Didn’t stop, and so they shot into it. A warning shot first, and then right into the car.

One evening in 1948, one of these hard-working men, Mr. James Watson, was returning in his car from a show not far from the Dew Drop Inn in Dawson Creek to his home in Kilkarren. With him were some friends and relatives. His son was driving while he, on the back seat, was holding a small child on his knees. Suddenly, the occupants of the car thought they heard a loud bang like a shot. Before they could decide what it was a second shot rang out. It was about nine thirty in the evening and they couldn’t see anybody. But Mr. Watson slumped over, shot through his chest. His son Fred stopped the car, still couldn’t see anybody. Someone screamed. And he turned the car around and rushed the wounded man to the hospital. He died three days later.

Now, leaving aside Wertham’s questionable grammar—do you think he realized that he’d implied the younger Watson died?—that’s a pretty compelling story. His insistence of how it’s obvious that crime comic books and only crime comic books that are to blame is less so. And yet the law that was passed because of it is still on the books in Canada to this day, technically making most comic books illegal there. Oh, sure, no one’s been charged with it since 1987, and the last person who was had the charge changed to “distribution of sexually explicit materiel” instead, but there we are.

Really, most of this chapter is given to page after page of people complaining about comic books. The person with whom I had the most sympathy was the unnamed medical director of the National Committee for Mental Hygiene, who said, “A child may ascribe his behaviour to a comic he has read or a movie he has seen. But such explanations cannot be considered scientific evidence of causation.” Wertham’s only objection to this is that it’s not children who claim such a causation, it’s adults. But of course that doesn’t make it right, either.

This is the thing that Wertham consistently fails to prove, in my opinion. He never successfully shows that these children are violent because they read comic books, not that they read these comic books because they’re inherently violent people. He rejects the very notion of an inherently violent person, but he does it without evidence. He can produce scores of letters to editors and speeches given in various courts and judicial bodies, but he produces not one scintilla of scientific evidence that the fault is comics.

He says, indeed, that the reason he can be so confident is that he is the only person whose focus is so narrow as to just look at comics. But is that not more likely to be evidence that he’s not considering other factors that may be as valid? After all, for all he is incensed that people keep saying things like, “But what about the movies,” even one of his own anecdotes strongly suggests that the boy it’s about was at least as influenced by movies. The boy is described as “talking out of the corner of his mouth,” perhaps like Bogart or Cagney?

He insists that the French perception of America as a place of gangs and gangsters stems from comic books, but of course we already know from their own writing that the gangster films of the French New Wave were inspired by the films noir of Hollywood. Did Jean-Luc Godard even read American comic books? But he and others of the Nouvelle Vague obsessed over American crime films, the very things Wertham is dismissive of in terms of possible influence.

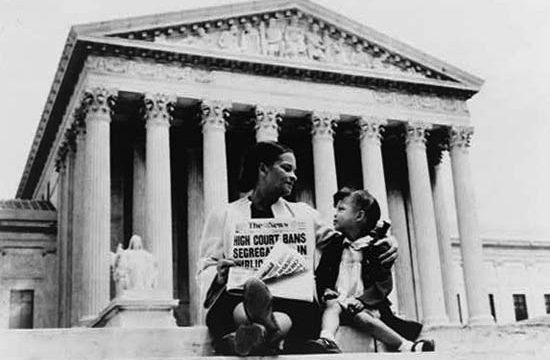

He says that it is America’s crime comics that create a negative view of the US in other nations, but it wasn’t. It was our news. The year Wertham was writing this book, the US Supreme Court was deciding whether the colour of a child’s skin was sufficient cause to keep the child from attending a quality school in her own neighbourhood. It would not be long before images of children being sprayed with fire hoses to keep them from peacefully demonstrating would be seen all over the world. Surely that was more important than comic books.

Wertham mentions that American crime comic books were banned in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union, but really, wasn’t most American art? He talks of Germans who did not need de-Nazification and feared re-Nazification, and how they thought Superman was something to be feared, but of course that ignores the whole “Jewish” thing. I mean, Hitler actually banned comic books too! He talks about a Mexican ban on comic books that “sow race hatred against Asiatic people,” but how much of that attitude is leftover World War II propaganda? It wasn’t just comic books that showed the Japanese as appalling sub-human stereotypes.

Again, there’s a thing that I feel some sympathy for; according to Wertham, “The Hampstead Burough Council of London debated a proposal to ask the London County Council to look into the effects of comic books on the minds of children.” He slips this into an enormous list of proposed bans, but this isn’t really a ban. It’s looking into whether a ban would do any good, whether a ban would protect children. Looking, in short, into the real influence comic books have on children. His beliefs to the contrary, this is pretty much the opposite of the work Wertham is doing.

So dismissive of the idea of other influences is Wertham that he speaks disparagingly of the fact that the words “crash,” “bang,” and “zip” being used in Italy. “Crash” dates to the 1570s and appears in Hamlet. “Bang” dates to the 1540s and appears in Julius Caesar, Othello, and Twelfth Night, not to mention T. S. Eliot’s “not with a bang but a whimper.” “Zip,” I grant you, is of considerably more recent vintage, no older than perhaps 1852. But is it so improbable that GI s loaded down with zippers and Zippos might in fact be the source of the word’s familiarity?