Ostensibly, of course, chapter thirteen, “Homicide at Home: Television and the Child,” is about, well, television and the child. In practice, it’s much more scattered than that. (One of the more minor but ongoing issues I have with Dr. Fredric Wertham is his apparent inability to write consistently on a single topic.) Not only is there the persistent criticism of comics, there’s also complaints about advertising, violence in film, and the idea that there’s such thing as a disturbed child.

Actually, on that last point, I talked with a friend online this week who quoted William Gaines, publisher of EC Comics and later MAD Magazine, as saying that “Wertham—like Spencer Tracy in Boys Town—couldn’t accept the idea of a bad kid, so he went out of his way to defend any young criminal by finding something else to absorb the blame.” Of course, Charles Manson did a brief stint at Boys Town before escaping with another boy three days later and committing a couple of armed robberies. No doubt comics were to blame somehow.

I mean, I don’t have any evidence that Charles Manson read crime comics as a child. How could I? I do know that Ted Bundy spoke lovingly of the violent TV shows he watched not long after Wertham was writing. And it’s true that TV is often appallingly violent. On the other hand, Wertham misses two points, one by dismissing it deliberately and firmly and the other by apparently never considering it.

The first is that far, far more people were exposed to violent media than became criminals. Wertham brushes this aside with a reference to people who carry infections diseases or have pre-clinical tuberculosis, but it’s still a fair point. My mom watched Disney’s Davy Crockett as a child, not long after this book came out, and my goodness but people miss how shockingly violent it was. More so than anything aimed at children today; I’m pretty sure fewer people die in a season of Deadwood, though admittedly Deadwood has a lot more sex and swearing. So why isn’t my mom a violent criminal? It’s true that crime rates went up for a while when my mom was a young adult and didn’t start going down again until she was middle-aged, but they didn’t go up sufficiently to blame the whole thing on EC and Davy Crockett.

The other is that there has to be a reason that people watched the stuff, that crime comics sold better than comics without. Wertham makes vague noises about how people are socialized to accept these things, but if children didn’t have an inherent fascination with violence, would the comics have sold well enough for the socialization to occur? Or would instead they have faded away like so many other fads?

Wertham claims that TV killed the dime novel, but he’s wrong. For one thing, well, the price went up. Hell, an issue of Life Magazine was twenty cents. So the paperbacks he’s criticizing in this same chapter are essentially dime novels, just priced higher. What tended to cost a dime in 1954? You guessed it—comic books. Though Wertham fights like hell to deny it, comic books were the heir to dime novels, to broadsheets, to police gazettes, and to all sorts of other mass entertainments considered too unsavoury for the groups that devoured them.

In this chapter, he criticizes a TV production of King Lear for the bruality of the scene where Gloucester is blinded, but he doesn’t seem to notice that it’s a centuries-old example of the “injury to eye motif” that he so frequently damns in comics. As Stephen King observed, of course we worry about injury to the eyes. Eyes are squishy, and there are all sorts of unpleasant associations with the idea of them. There are few body parts that cause a more visceral reaction, I suspect.

Basically, though, if I were to sum up the whole chapter, it would be with an observation that Wertham doesn’t have any familiarity with the history of popular culture. He talks about how other media need to fear censorship because of the graphic nature of comic books without apparently any awareness that movies at the time were being censored, albeit not by the government. In fact the restrictions under which movies were placed were intended as a replacement for the then-extant governmental censors of several jurisdictions. Obviously, he’s writing before Sally Field and Barbara Eden were required to keep their navels covered, but television wasn’t exactly completely free of limitations, either.

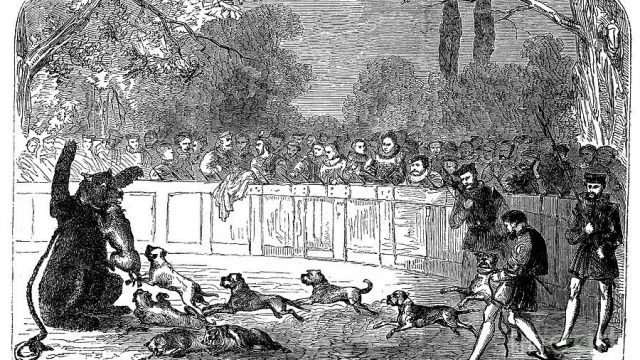

He holds up Hamlet as, yes, a play where he kills five people, but also one with dignity and beauty and so forth. But again, he criticizes that production of King Lear, and if he really wants to defend violence in Shakespeare, let’s start with Titus Andronicus, which also throws in a healthy dose of racism. Or, really, an unhealthy one. And I mean, never mind that what we now call teenagers were regularly in attendance at bear- and bull-baiting at the time!

Wertham rejects “same as it ever was,” but he does so without justification. The idea of childhood is, in many ways, a fairly modern one and one of intense privilege. You can afford to have children who don’t have to earn their keep in some way. And that may be the biggest problem of all with this chapter, maybe the entire book. Wertham isn’t wrong that the psychological needs of children are different than those of adults, but he’s entirely wrong in assuming that we’ve always known that.

Psychiatrists in those times would not admit that an ordinary boy could hate his father or a daughter, her mother. Bernard Shaw wrote about that, but the psychiatrists didn’t.

So okay, but had he missed the Oedipus complex described by his mentor, Sigmund Freud? Because that was the first thing I thought of. At the time Wertham was writing, the word “psychiatrist” was less than a hundred years old, the word “psychiatry” barely over that. Any psychiatrist from that time who wasn’t aware that perfectly ordinary children can hate a parent hasn’t spent much time with children. Or studied history—look at the children of Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine, though I’m not sure “normal” quite covers them!

But Wertham would apparently have rejected the idea that Henry and Eleanor shaped their children, since he seems to believe that outside influences matter considerably more. I guess possibly it was all those ballads the boys were listening to? He also relates an anecdote about Goethe wanting to buy a toy guillotine for his son in 1795 while insisting that toy weapons for young children were a completely new phenomenon in the mid-twentieth century.

Actually, you know, I watched the Disney Davy Crockett at about the same age as my mom did, now I come to think about it. Zorro, too. Maybe I didn’t grow up on violence in quite the same way that my mother did, but you know, my mother also wasn’t one of the children who’d been brought to a clinic for violent behaviour. Maybe Wertham should have included her, and children like her, in more of his studies.