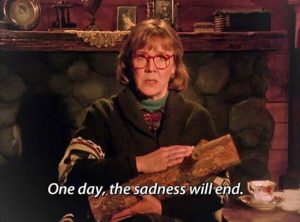

In season three of Twin Peaks, there is a tiny subplot in which Margaret Lanterman, more famously known as the Log Lady, calls Hawk to fill him in on clues her log has given her before she passes away offscreen. In the first two seasons, Margaret was a classic case of a comic character who we gradually realise has a better grasp of things than everyone; her ridiculous pronouncements are mostly proven accurate in a roundabout fashion. Even if they weren’t, her stubborn committed belief in everything she does quickly becomes endearing, particularly because she proves herself totally benign. She becomes an warmly familiar aspect of life in Twin Peaks, like an old pair of shoes. Her appearance in season three is shocking and sad – she is visibly very ill and weak, and worse, she looks terrified. Of course, there is the fact that Margaret is played by a real human being who was, herself, so ill at the time of shooting that she passed away before the season aired; I can imagine the suffering she and her loved ones went through and be moved by that. But there’s also my innate inability to fully comprehend the fact that the Log Lady is dying.

I’ve written about how The Shield shows people turning temporarily into icons; this is a case of an icon degrading into a person. An icon will get up and do exactly the same thing every single day – however we might interpret him, however we might feel about him, no matter how many people write hot takes that he’s a rich guy beating up the mentally ill, Batman will get up and fight crime every day (or every night, I suppose). Fiction especially has a habit of freezing its characters in amber once the story finishes, and Margaret is one of the few citizens of Twin Peaks whose dynamism came in how we perceived her rather than change in anything she did – every episode, she gave her stern, comical pronouncements. Seeing her sitting in her chair, oxygen tube hooked up to her nose, breath unsteady; it’s like seeing the sun struggle to rise. What haunts me most is her sense of palpable terror.

I’ve read that one thing that’s nearly universal in human cultures across the globe and across value systems is that we valorise facing death with dignity. I have always found this a selfish imposition on people at the weakest moment they’ll ever be in. I have been convinced that death is not the worst thing there is, but I still think it’s up there. I can’t decide what’s worse – that there’s nothing after death or that there’s something after death. To mock someone because their reaction to death – their own or someone else’s – doesn’t strike you as dignified strikes me as anti-human. To see someone as unflappable and obstinate in her existence as Margaret show fear and weakness is to see all my fears of dying presented unvarnished. What I see in her final scenes is her desperately begging for one last bit of recognition – that someone, somewhere, cared about her existence before it gets snuffed out. I think Hawk sees this; he says her name a lot, as if to say yes, I hear you, you’ve been alive and I want to remember that.

I think the reason people want to be icons is because icons don’t die. Many so-called ‘deconstructions’ justify their existence by shaming us for believing in icons (random example: The Boys). This feels more effective because it comes from a place of love both for Margaret and for me. I love Margaret and it upsets me to see her vulnerable because I honestly believed the Log Lady was incapable of dying. I imposed a sense of immortality on someone who could never have lived up to it. What’s funny is that she won me over simply by existing so memorably. Moving the plot along at the end was nice, but I really loved her because she said a lot of funny shit without hurting anyone (unless you count slapping Cooper’s hand when he went for a biscuit before getting his tea). I’ve never been able to accept the notion of judging someone for their utility to others; the morality of an artist, I suppose. But maybe I’ve tried to judge people by their ability to be icons too much. Perhaps icons are the way we should give name to the past and the future; applying them to the present has cruel outcomes for all of us.