Film is mercilessly visual. Its closeups, the clarity of the image (which only gets clearer with the development of digital technology and high frame rates), the way the camera captures everything, conscious and unconscious, and probably most of all the way we react to images without thinking or criticism: all of these things mean that appearances and surfaces matter most in film and there’s no way around that.

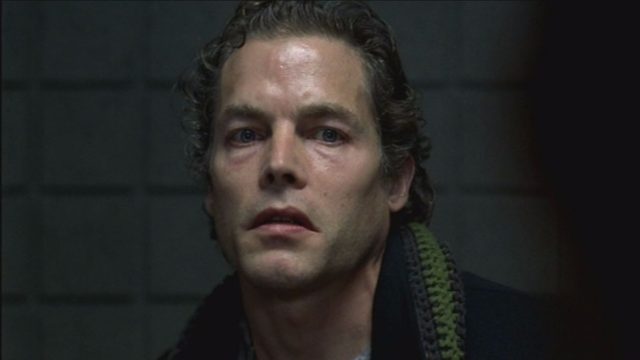

One consequence of this is that some people will forever and only be character actors. Michael Massee, who died last week, had a prolific career in movies and television but was never a leading man, and he was never going to be. Most of his roles were as the bad guy, not the criminal mastermind but the sleaze; 24 and Lost Highway come to mind. His lips were thin, making him always look threatening; his cheekbones were zombie-prominent; the voice low but not seductive. Those exaggerated features made it impossible for him to be leading-man sympathetic but made him just right for the minor roles, where it’s necessary for him to communicate who he is before he says anything. (David Lynch got that in Lost Highway, where he could simply be a hallucination of Bill Pullman’s character. Lynch had to put Robert Blake in makeup for that effect, but Massee and Robert Loggia already seemed to be not of this earth.) David Fincher cast him in a single scene in Seven, and it says how talented both of them are that Fincher got more out of Massee, and more quickly, than anyone else.

The scene is one that Fincher and screenwriter Andrew Kevin Walker repeat all through Seven: the scene of witnessing. It’s a strategy that began with the autopsy in Alien³ and will become the substance of Zodiac: we do not see what happens, we do not see the dead; rather we see those left behind, struggling to make sense. “We’re picking up diamonds on a deserted island,” says Morgan Freeman’s Det. Somerset, “saving them, in case we get rescued.” It’s a strategy that denies conventional catharsis–no cool killings to cheer–and creates Seven’s unique, old-school morality, one in which the actions of the heroes mean nothing, so their sympathy, and ours, mean everything.

Following on the aftermath of the Lust murder, where Fincher uses Det. Mills’ (Brad Pitt) body to block the presence of any gore, Mills and Somerset interrogate two men: Somerset takes the man (Leland Orser) who was forced at gunpoint to rape the woman to death with a ornate bladed dildo; Mills takes Massee, who runs the place where it happened. (Great and typically Fincherian detail: the wound from the gun, visible on Orser’s mouth.) Unlike the best scene in Zodiac, Fincher uses only closeups here after the establishing shot, never letting anyone be seen in anything but their own frame. There’s a countersymmetry to the way the characters are paired: the quiet, reserved Somerset gets the increasingly panicked Orser (“OH GOD OH GOD OH GOD HE HAD A GUN IN MY MOUTH”); the volatile Mills gets the quieter Massee. Fincher shoots Orser with slightly more distance than anyone else, and Somerset from below and close. Somerset comes across to us as he does to Orser: as a judge, as a force. Massee and Pitt get the same medium-close shot, both at eye level.

Seven has a lot of great quick, even one-scene performances, and Orser has one of the most memorable. It’s not just the panic, but the way he precisely modulates it; he gets worse with every word, starting with terror and finishing the scene close to epilepsy. It does what so much of Seven does: first, bringing the horror of what we don’t see to us. (Also, it says everything about the killer’s raging hatred of women that he chooses the prostitute–”the disease-spreading whore”–to kill for Lust, and not Orser.) More subtly, though, it plays on something that began with the first shot of the movie, and continues through Fight Club and Zodiac: show irrational, messy reality breaking into an ordered world. From the first shot of Freeman’s aging, slack body among clean verticals, Fincher opposes roughness and reason, and Orser’s panic breaking into and overwhelming the clinical interrogation cubicles is one more stop on the journey; so is the way that white towel pops against cinematographer Darius Khondji’s dark tones.

Yet Massee may have even more impact, with even less. Another journey in Seven is Mills moving away from idealism. (Before the credits start, he sez that he transferred to the city’s worst precinct because “I thought I could do some good.”) Fincher shoots Somerset like a judge, but Mills is the one who’s trying to judge; Pitt plays the scene with such formal politeness and underlying hostility, angry that Massee let this happen. Across the table, this is clearly not Massee’s first encounter with cops; he knows that he’s in the clear legally, he knows that part of his job is not looking too closely, especially not at what men carry inside. Also, that hair gel gives him an extra layer of sleaze. The punch of the scene, the moment I didn’t see coming, happens when Mills throws his most judgmental line: “do you like what you do for a living? The things that you see?” and Massee literally leans into the figurative blow, and counters with “No. No I don’t. But that’s life, isn’t it.”

The things that you see: this is what Seven is really all about. It’s a film about witnessing, about being helpless to do anything else, about witnessing sometimes being the only honor you can give to the dead. The true climax of Seven isn’t Mills gunning down John Doe–that was Doe’s design, and Pitt plays that moment with such futility, like what else are you gonna do with those bullets?–it’s Somerset turning away, a compassionate man who has finally seen too much, and can’t watch this. A lesser actor than Massee would have brought anger into “No. No I don’t,” but he hits it with a deep certainty; it’s like Jennifer Lopez saying in Out of Sight “you have to know what you’re talking about.” It’s weary conviction, but not righteousness, because witnessing doesn’t make you right. Massee’s tired assertion “that’s life, isn’t it” and the equally tired look he gives Pitt as he leans back throw forward to the last lines of Seven, Somerset narrating “Hemingway said ‘the world is a fine place, and worth fighting for.’ I agree with the second part.” Both Somerset and Massee get it: the world is not good, but we are obligated to live in it and witness it anyway.

This is a moment in the film where Mills still has some ideals (the next scene has him asserting those ideals to Somerset); Massee left them a long time ago. Massee’s acceptance of the world-as-it-is keeps him alive, and Mills’ refusal to accept will break him; his final act–killing Doe–is an action, and a completely self-destructive one. (For that matter, so is his first act, before the film even starts, of choosing to come to this precinct.) Fincher so carefully composes the smallest details of Seven into a larger thematic whole, and Massee appears in this scene not just as a counter to Mills, but as a warning. So many filmmakers saw only evil in him, but Fincher found a morality there, and used it for the disturbing medieval vision of Seven.