Kevin Smith has been defined for so long by his inability to give a shit about the basics of filmmaking that contemporary audiences might not realize how strong his voice was in the 1990s. Clerks had as much of an impact on me (and others) as Reservoir Dogs did; there was the same feeling in both of what Charles Bukowski called “the obvious thing no one is saying.” The black-and-white single-camera aesthetic was perfect for its story of a day in the life of people not going anywhere, and it’s still my favorite comedy. (There’s nothing that feels as right at the end of a bad day than to say “buncha savages in this town.”) I remember doing the calculations and figuring that there could be 500 or so Clerks for every Terminator 2. That seemed really promising for independent films in the 1990s.

Chasing Amy remains his best film, the last of the interconnected stories of the New Jersey trilogy (the first two films are Clerks and Mallrats) and the first of what could be called the Something Personal to Say trilogy (the next two are Dogma and Jersey Girl), three films about, respectively, his love of Joey Lauren Adams, God, and his daughter. It’s not the work of a great talent, but of someone greatly expressive and agile within a limited talent. That Smith worked with his longtime collaborators here helped that expression; no one would call David Klein a better cinematographer than Vilmos Szigmond, but Chasing Amy (shot, like most of Smith’s films, by Klein) is a far better film than Jersey Girl (shot by Szigmond and appreciated here). (Citing the importance of being comfortable with who you work with, Smith went back to Klein for Clerks 2.) Smith doesn’t do much with camera moves, but his sense of framing and editing here is impeccable. You can see that here, almost a Five Obstructions-type challenge: a scene with an immobile camera and two insert shots.

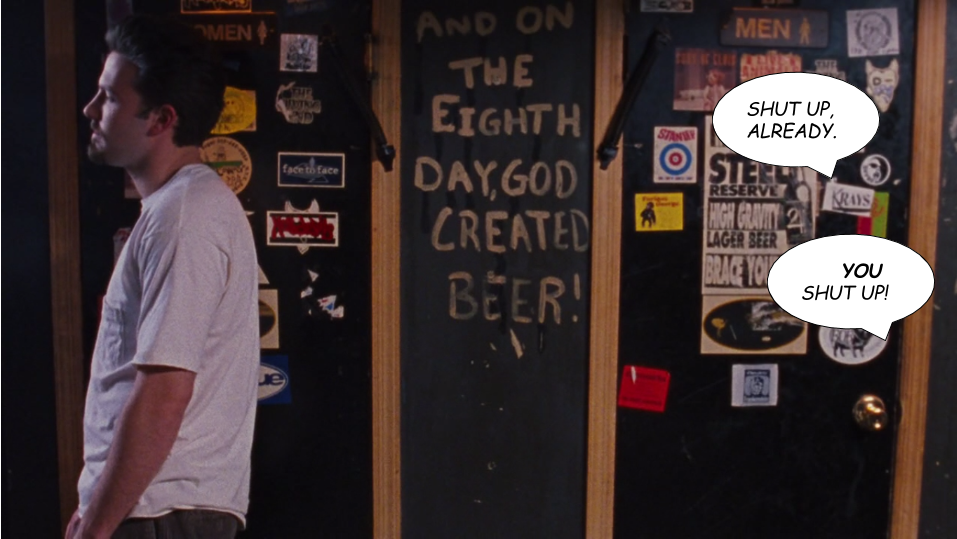

This scene follows up on the previous one, with two stories going on. The first has Holden (Ben Affleck) and Alyssa (Adams) getting to know each other; Smith or Affleck says that Holden is trying to be charming but it’s not quite landing, and he’s aware of it. The second has one of Smith’s classic pop-culture debates, whether or not, as Hooper X (Dwight Ewell) sez, “Archie and Jughead were lovers.” Jason Lee’s Banky, shall we say, objects to that (“SHUT THE FUCK UP!”) and as he and Hooper go off to find some comics so Banky “will show you that Archie is all about pussy,” Holden and Alyssa go off to play darts. (On the commentary, Smith sez “Jason Lee does ‘coiled spring’ like nobody’s business,” and any time that spring springs, it’s comedy gold I tells ya. His absolute conviction on the line “because he wanted them both you assholes! He never settled on one of them because he was trying to get them both into a three-way!” remains so very quotable.)

Like Tarantino’s dialogue, Smith’s could be described as highly stylized and derived from naturalistic elements. His characters have elaborate, stagy monologues and conversations but they come from the everyday language (and references) of the 1990s, with references to the original Star Wars trilogy at a premium. (Hooper’s speech on racism in the Trilogy is another one of Smith’s comic triumphs.) Smith’s style helps that; by setting down the camera and having it simply watch the characters talk, it allows the actors to bring a natural rhythm to what they’re saying. Smith rarely shoots coverage (shots on characters or something else that isn’t speaking), so the actors have to play the scenes all the way through. It’s a style more theatrical than cinematic.

First up, the background; if the camera watches it all the time, it had better be interesting. Having two bathroom doors at the sides of the frame does that nicely. It looks like comic-book paneling, and as we’ll see later, it allows for comic-book effects. It also creates some strong vertical lines that keep Holden and Alyssa slightly apart from each other visually, which is the right tone for this scene. The labels on the doors add another layer of interest; on this viewing, I caught the “Bloomsday” sticker on the right-hand door. Finally, these are bathroom doors, which mean people will be going in and out of them for the whole scene, creating more visual activity. There’s a bit of foreshadowing in the background, too: it’s only men coming out of the womens’ bathroom, and vice versa. Gender roles are not stable in this movie.

Smith’s reflexive composition has been called “I Love Lucy blocking”–two or three characters on a horizontal line at a fixed, medium distance from the camera. (I believe that description comes from one of the commentaries on Dogma. Listening to the commentaries, I wonder how much of Affleck’s impulse to become a director came from working with Smith and thinking “shit, I can do better than that.”) It can come off as static when there’s not a reason for it, and having Holden and Alyssa play darts gives it one. It also creates an axis of motion here, as they throw darts and walk up to the camera to to retrieve them. Klein uses some subtle rack focusing on the characters as they move forward and back–nothing showy, but the scene would be less dynamic without it. The blocking helps the emotional tone of the scene. For most of this conversation, they’re talking to each other but not looking at each other. Filming them straight-on so we can see both of them at once makes us see and feel that directly; if Smith cut to isolated talking heads, we could only infer it. They’re open with each other, but a little wary, especially Alyssa.

On the surface of the conversation, two people are getting to know each other, that kind of not-exactly-a-first-date moment where what’s said doesn’t count quite as much as the sense of who someone is. (Call this “making a second impression.”) There’s a layer of the conversation that points to something about who Holden and Alyssa are: when Holden sees a couple making out on Banky’s car (the first insert shot), he says “you have to respect that kind of passion” and she dismisses it with “that’s fleeting.” Already, we get the sense that Holden can be carried away by a romantic impulse and Alyssa stays more realistic, and more honest. That throws forward to the biggest scenes, because Holden always has an image of how things should be and Alyssa will always undercut that and try and convince him to accept what’s real. It’s clearest in the climactic scene, but it’s also the emotional core of the scene in the parking lot of the hockey rink. That remains one of the most searing things I’ve ever seen, and one of the most affirmative; no one gets to decide the narrative of Alyssa’s life except her.

The second insert covers a major edit: Alyssa had a long monologue here about her mother’s uncle and what commitment means, “the original love story.” It’s a somewhat mystical “Monkey’s Paw”-type story, it sets up Holden staring off into space later in the scene, and Smith removed it. He felt that it was something too heavy for this moment in the film (fifteen minutes in) and it also would have made the scene over twice as long. (It also ruins Holden’s line “you see that dent on the hood of your car?” which I always read as meaning the couple was still on it.) For all the digressions and ramblings in a Smith film, he was fairly ruthless about cutting at this stage of his career; the original draft of Chasing Amy was over 160 pages long. Smith took out at least a third of it to get to what we have here, which looks to be about how much he cuts from all his scripts.

When Alyssa leaves (on a second axis of motion, left-right), Smith leaves Holden near the left edge of the frame with a big chunk of negative space to the right–the white shirt provides a nice contrast too. It’s a great anticipatory shot, a massively unbalanced image looking to right itself and that serves as a visual setup for the next part of the scene. In Clerks, Smith used offscreen space well–with only one camera, he had to. (Think of Randal’s “37?” or the arrival of Caitlin.) Here, we hear Hooper and Banky before we see them, another comic-book effect–you can imagine the speech balloons on the right side of the frame. They come into the frame with the argument already in progress, and Banky, as promised, has picked up the Archie comics. (A great touch from Smith’s Comic Book Guy side: Banky carefully puts the comic back in its plastic sleeve.) Comedy depends a lot on the audience filling in the blanks, and this argument has clearly been going since the end of the preceding scene. (Thanks to Miller for noting this.) Hooper and Banky settle nicely into the other two panels of the frame (in true comic-book style, Holden doesn’t move at all) and the scene continues with some more great Smith dialogue. Having Hooper say “read between the lines bitch” just slightly off center-frame perfectly stages a perfect line–his position is itself a kind of eye-roll at Banky–and having Banky continue moving and exiting frame left echoes the best gags of NewsRadio. (Donna Bowman called it “the signature Newsradio shot: a static medium shot in which a character runs full speed into or out of the frame.”)

Smith ends the scene with a simple and effective transition. (“Simple and effective” describes all of Smith’s best direction.) Switching into “Run’s House” at the cut shows his continued love of 1980s culture, and it also serves as a distraction. The last exchange of the scene (“Let me guess, you like her.” . . . . “She’s alright.” “As long as that’s all that it is”) suspends something, especially with the cut on Hooper just looking at Holden. Before we–and Holden–can wonder what he means by that, the song kicks in and there’s also an internal edit, jumping closer to the BANK HOLDUP STUDIOS sign. Both of these jump us and Holden away from the importance of that moment–the longer we hold on Hooper, the more significant it is. (And if the transition had been a dissolve with no score, it would also become more significant.) The edit with the cut and music conveys that Holden didn’t get it, and we see in the next scene that he didn’t, saying that he and Alyssa “shared. . .a moment.” Affleck’s little hand gesture is another classic–this may be his best performance, because he’s willing to be so utterly without clue.

Great directing isn’t defined by camera moves or actor preparation or framing or color timing; all of those are elements of directing, not definition. Directing is like any other element of cinema: what’s great is what is necessary for the work. Smith was never going to be an innovative, transformational director, but by this standard, he was potentially a great director. Chasing Amy remains my favorite of the 1990s wave of independent films, and it’s a loss to all of us that Smith never got back to that level of commitment again.