Content note: this article contains a reference to suicide

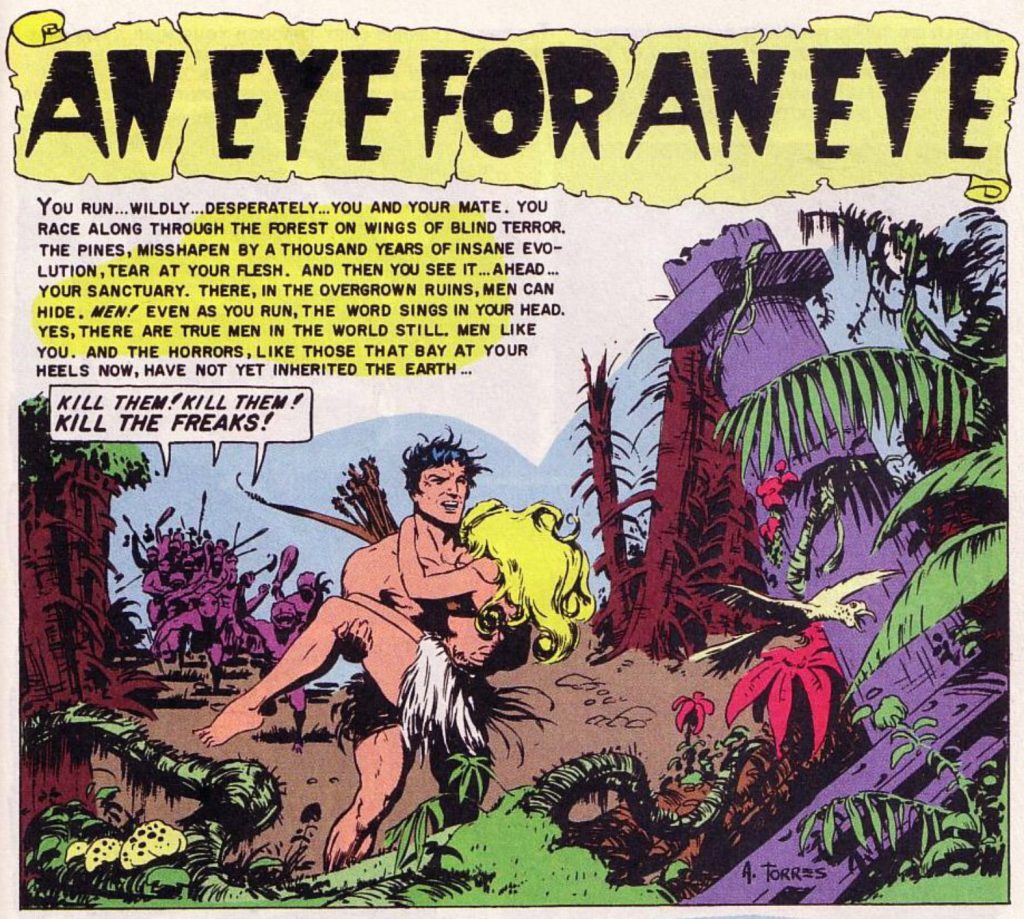

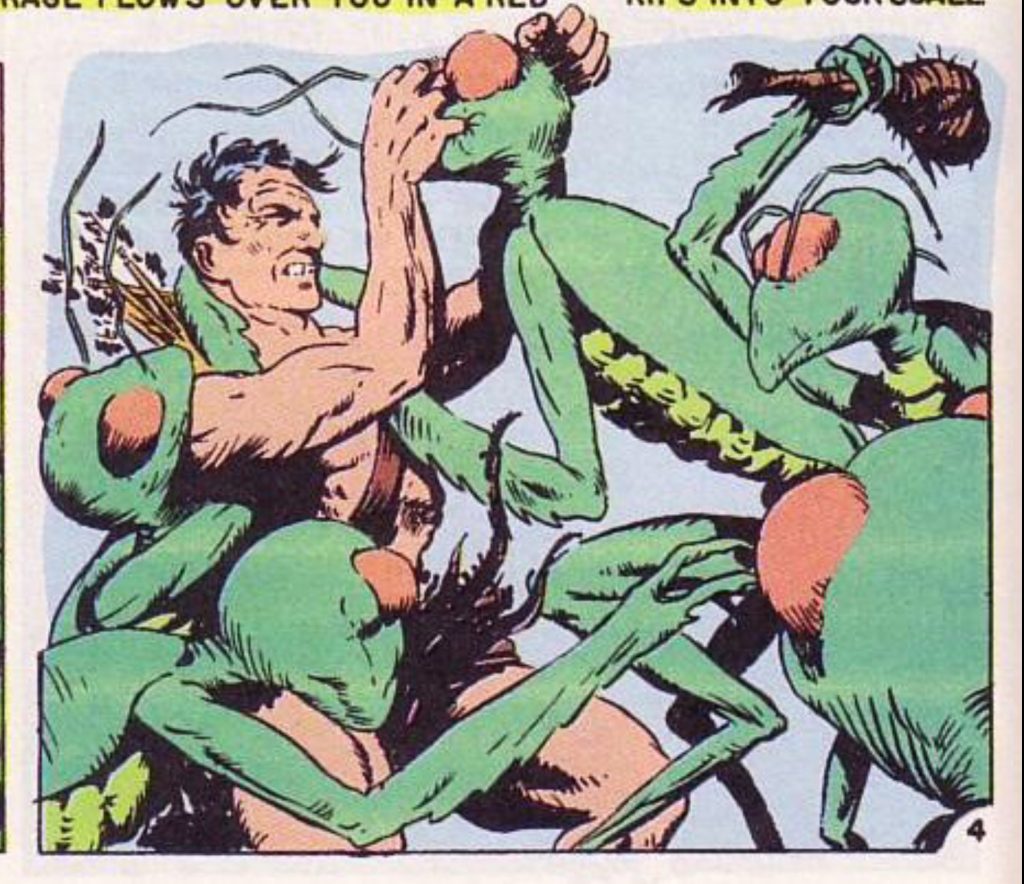

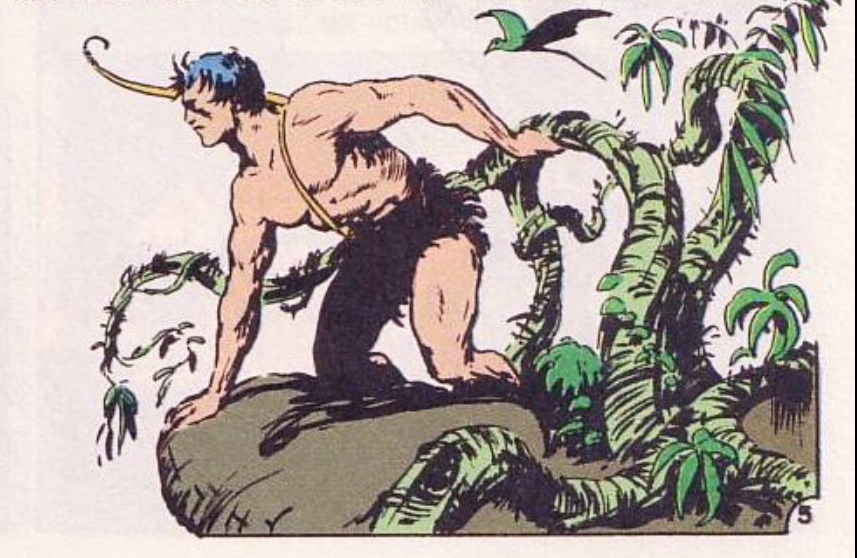

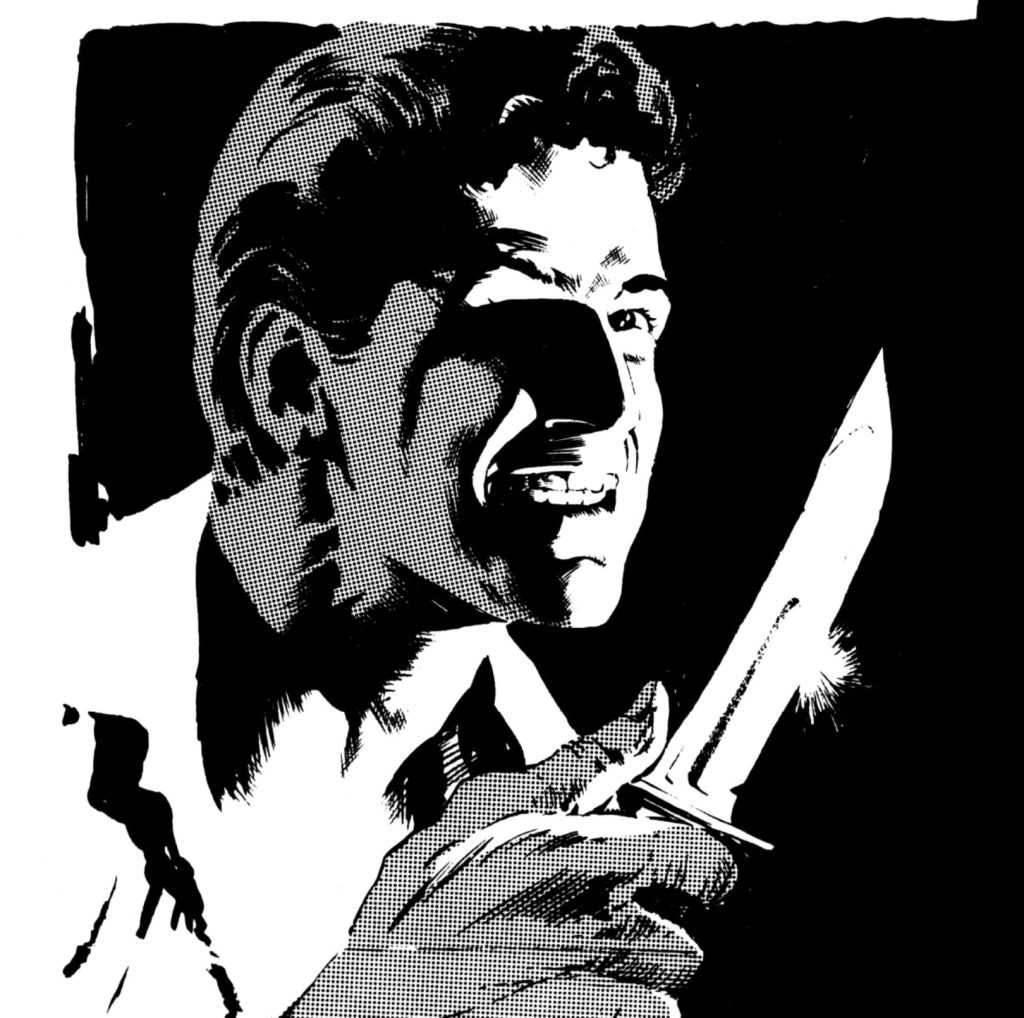

EC put most of its eggs into the Picto-Fiction basket, but one last traditional-format color comic staggered onto the stands in 1956. And the backstory behind makes it clear why it was the only one. The Comics Code Authority refused to let the final story in Incredible Science Fiction #33 go to press. It’s hard to see why — “An Eye for an Eye” is violent but almost entirely bloodless. It’s also a great example of EC’s overlooked role as a talent incubator. featuring beautifully textured and dynamically rendered art from Feldstein and Angelo Torres, who’d go on to be a major figure in the horror comics revival of the ‘60s and ‘70s.

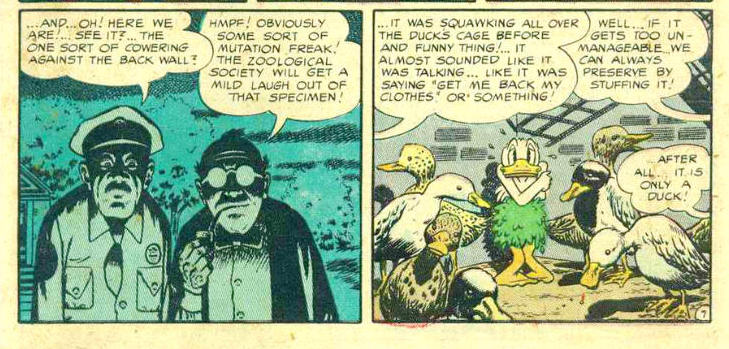

Whatever the reason for the backlash against “An Eye for an Eye,” it only got worse when Feldstein replaced it with a reprint of the Joe Orlando-illustrated integrationist parable “Judgment Day.” Feldstein was baffled by the Authority’s demands he whitewash the Black astronaut who takes off his helmet in the final-panel twist: “But … but that’s the whole point of the story!” They might have had a point in that the allegory of Feldstein and Joe Orlando’s story of a planet of red and orange robots was already painfully obvious, but it’s a safe bet their reasons were far less defensible. Two years into trying to negotiate with the Code, EC finally gave up. When the Code’s Judge Murphy proposed a compromise, Feldstein and Gaines yelled “Fuck you!” into the phone in unison and ran the story unaltered.

Only Mad would live to see the year’s end, and even that exited 1956 in a radically different form than it had entered it. Harvey Kurtzman’s decision to take Mad off the comics rack and onto the newsstand had paid huge dividends, and he wasn’t seeing nearly as much of them as he would have liked. So when Hugh Hefner poached him for a new magazine, Trump, Kurtzman tried to leverage the offer for full control of Mad. Feldstein countered with an insultingly small promise of a 10% share, and that was the end of that. Kurtzman felt like Feldstein and Gaines were ungrateful bastards to him after he saved their company, Feldstein and Gaines felt like Kurtzman was an ungrateful bastard to them after they kickstarted his career, everyone went home unhappy. It feels especially petty seeing Gaines’ name in big letters on the year’s paperback collection:

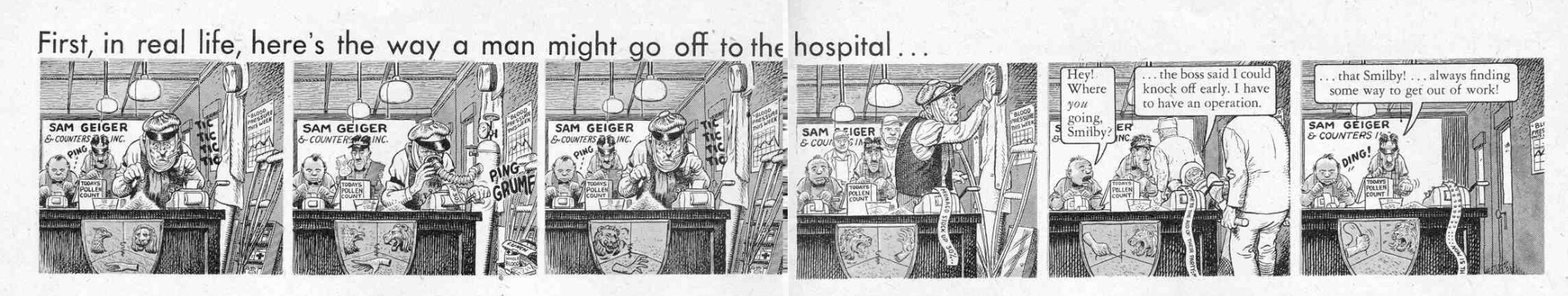

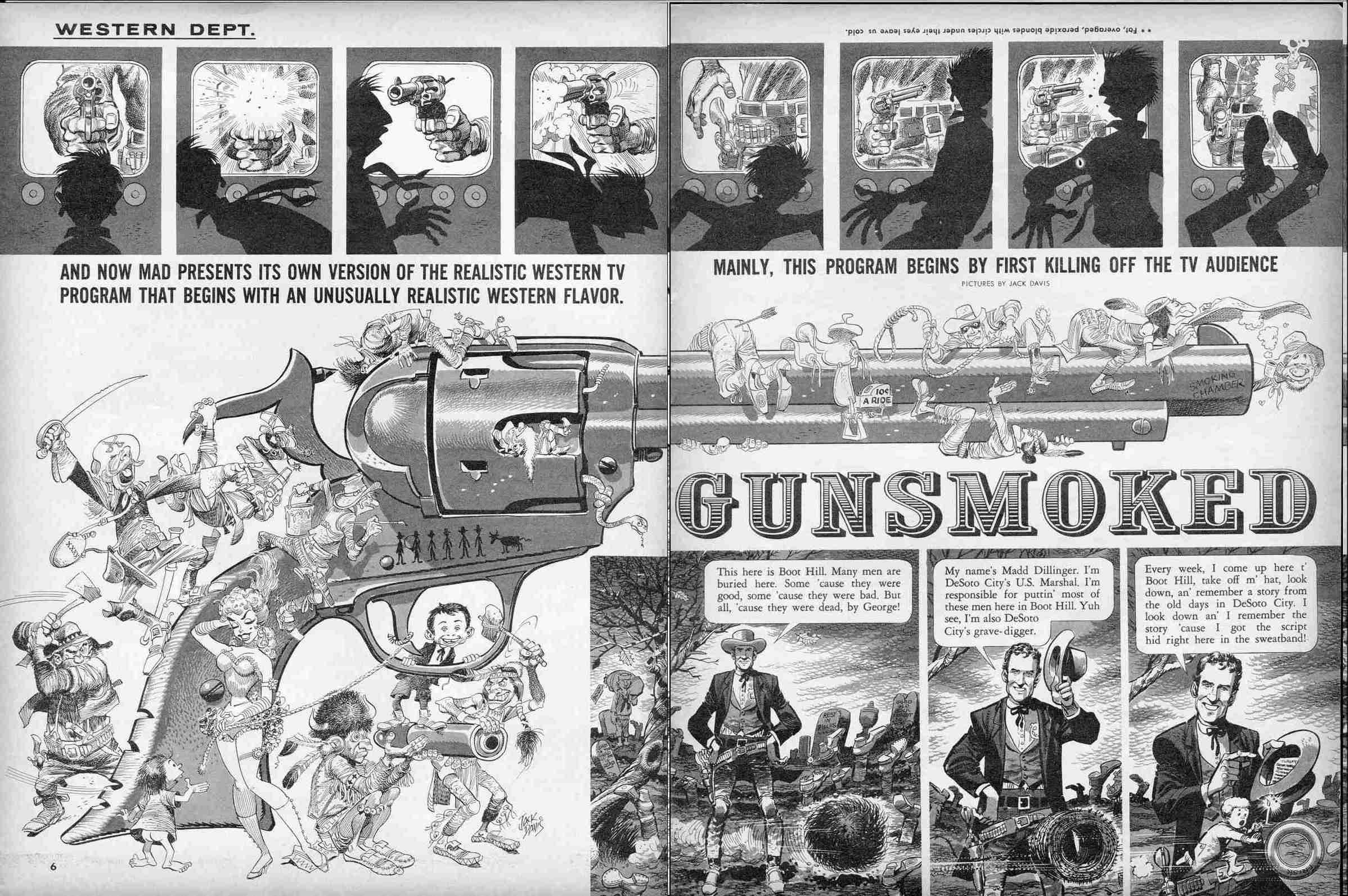

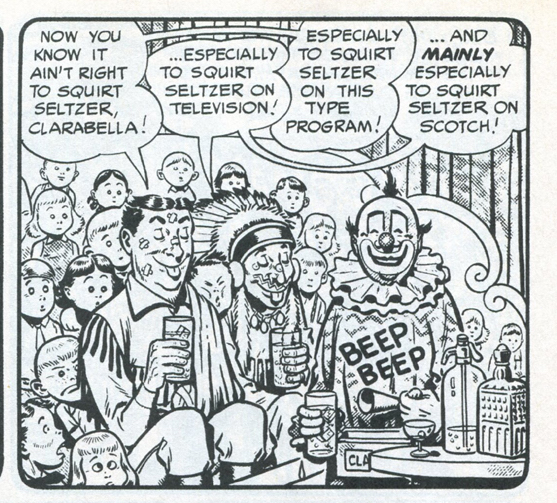

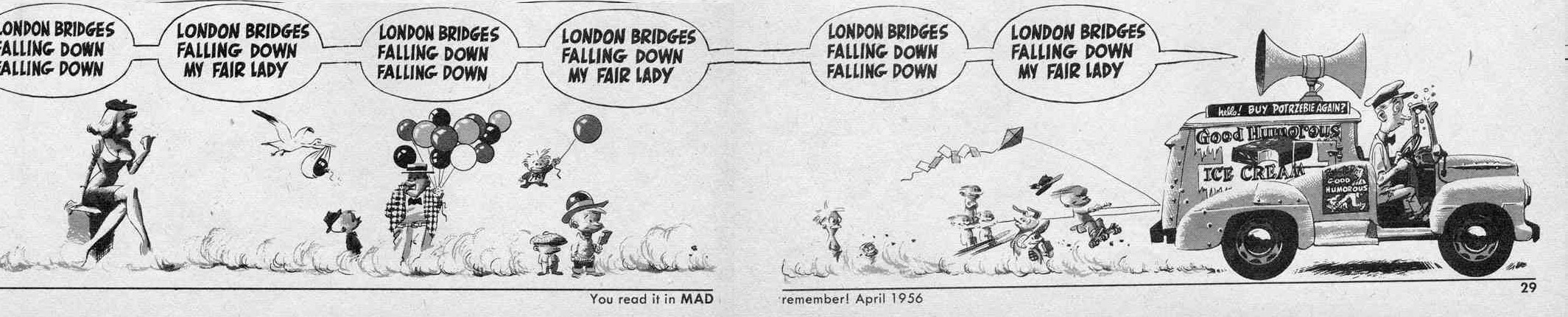

But divorce can be hardest on the child. So what happened to Mad? Well, it came out of the whole mess bigger than ever, but as soon as I saw the “editor” credit on issue #29 change from Kurtzman to Feldstein, I could smell the flop sweat soaking the pages. To Feldstein’s credit, his new writers do a good enough imitation of Kurtzman’s unique blend of repetition, newspaper-headline terseness, and Yiddish-inflected nonsense poetry I probably wouldn’t have noticed the tradeoff if I hadn’t known about it going in. To his discredit, once you do know the background, it’s hard to see the late-’56 issues as anything but a strained, uncanny-valley imitation of Kurtzman’s style. The new staff were particularly fond of this bit of Klassic Kurtzman Konstruction, as demonstrated by this scene from the 1954 story “Howdy Dooit!”

There’s like five or six examples of post-Kurtzman Mad ripping this off, but I’ll go with this one, if only because it’s how I learned people have been saying “lit” way longer than I’d thought.

The last issue of the year even rips off a gag from the first almost verbatim:

Kurtzman’s final issues show what a loss his departure was. He didn’t just write the stories — he did a good chunk of the artwork: like John Stanley, he turned in his scripts as rough “storyboards” for his co-artists to flesh out. None of these sketches have survived, and it’s unlikely he drew in all the weird little background details — what artist Will Elder called “chicken fat” — but there certainly seem to be a lot fewer of them after he left. (and unlikely isn’t the same as impossible: One of his war comics collaborators remembers getting a storyboard where Kurtzman drew a crowd scene so detailed “You could read all their nametags.”)

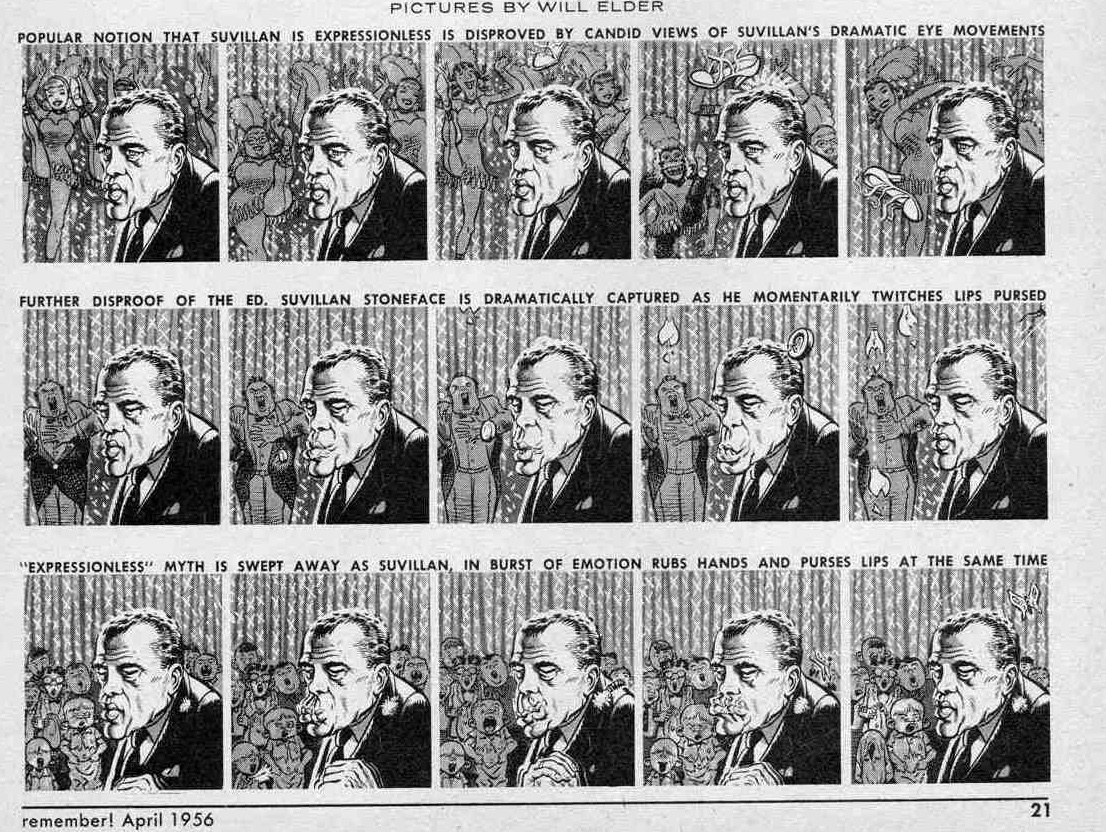

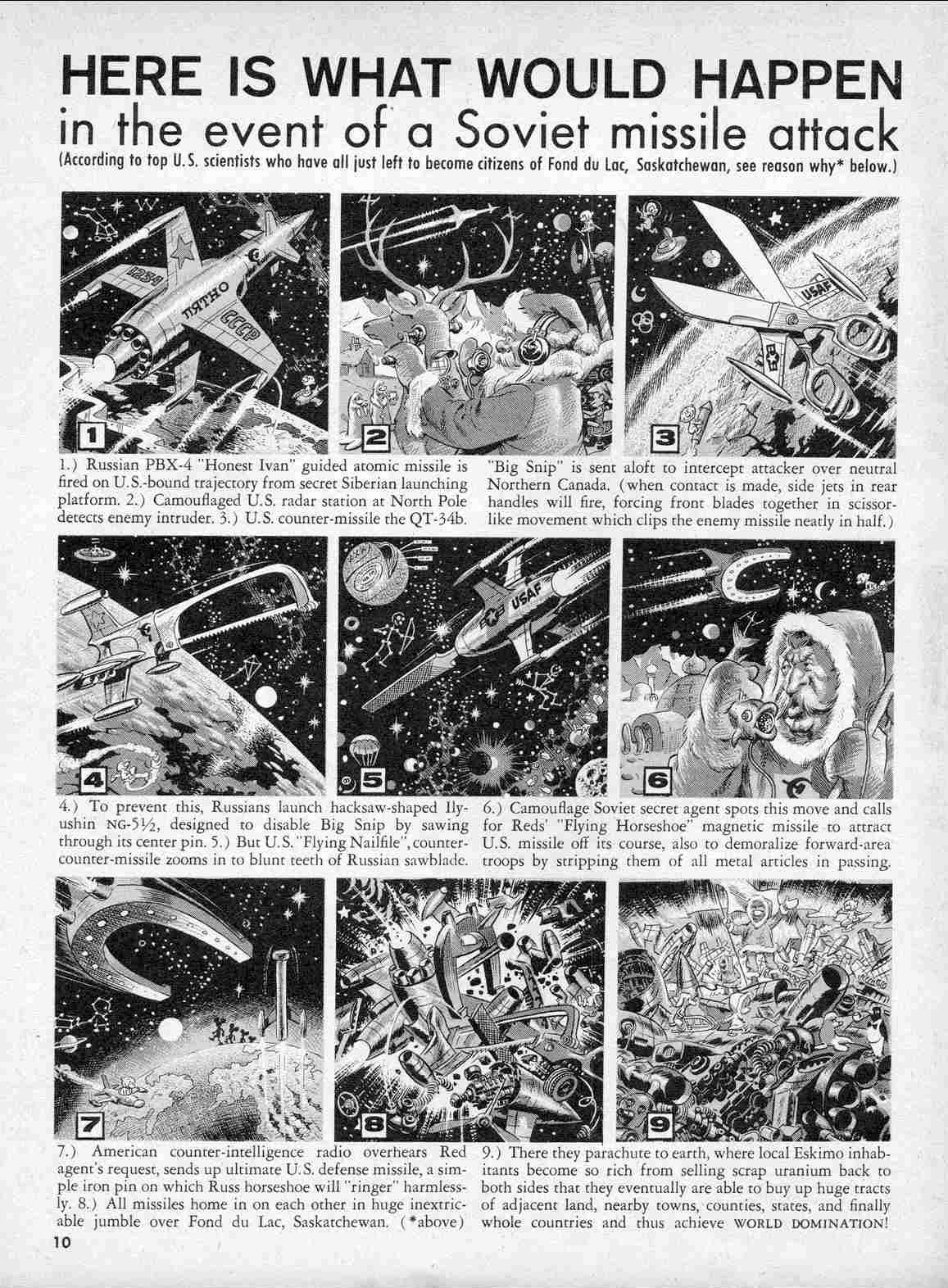

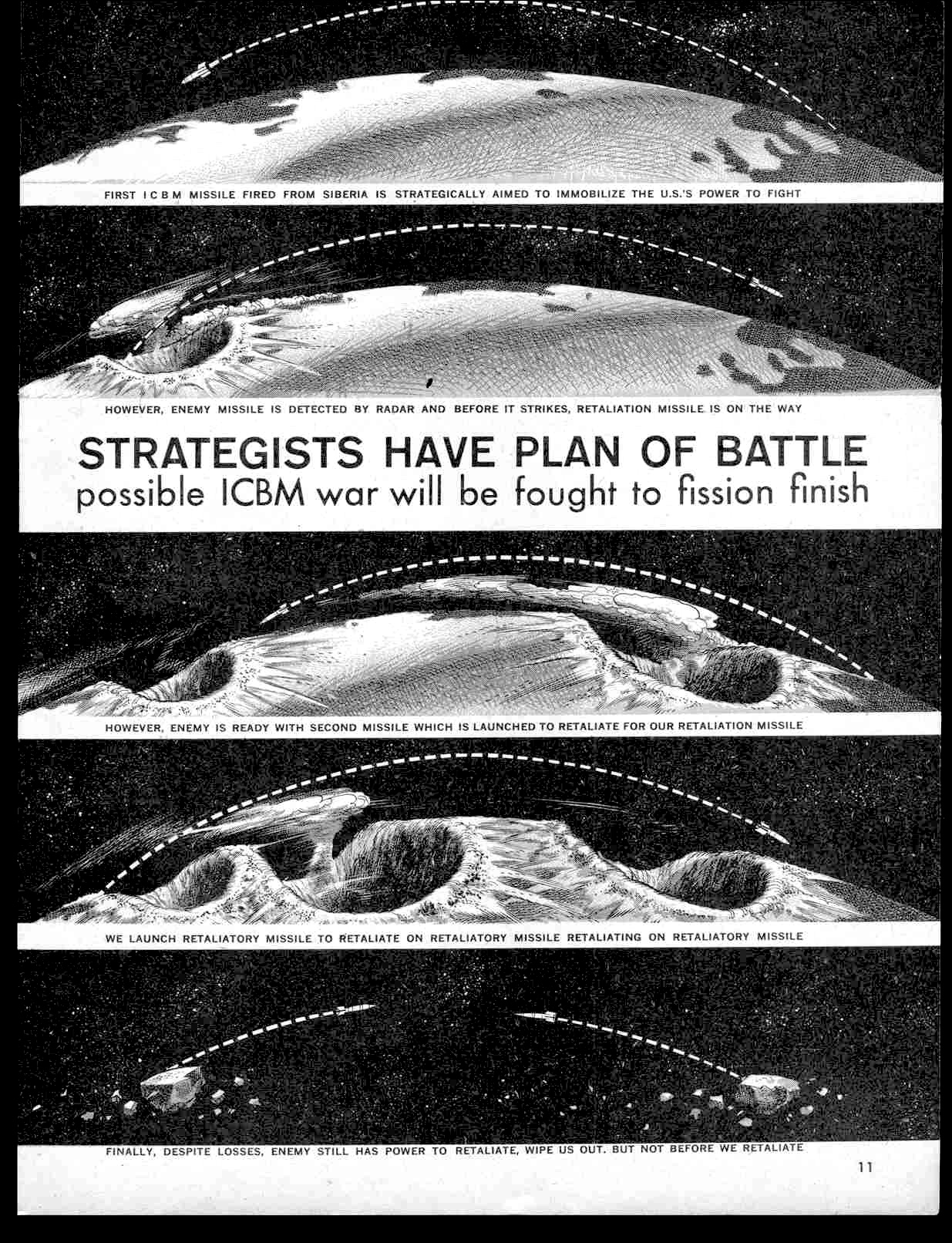

And that’s a shame, because chicken fat was one of Kurtz-Mad’s greatest strengths. Even as he departed even further from the comics format than the Picto-Fiction books, with even more text-heavy parodies of magazine articles, chicken fat is still the kind of thing that can only exist in comics. Possibly inspired by the constantly shifting Southwestern landscapes of George Herriman’s Krazy Kat, each panel of Kurtz-Mad is packed with new gags. In any other visual medium, you’d need to smooth out these transformations, but in comics, they can happen entirely in the gutters. And while other artists tried to imitate him, Kurtzman gave his chicken fat some extra oomph by changing the main action across panels as little as possible.

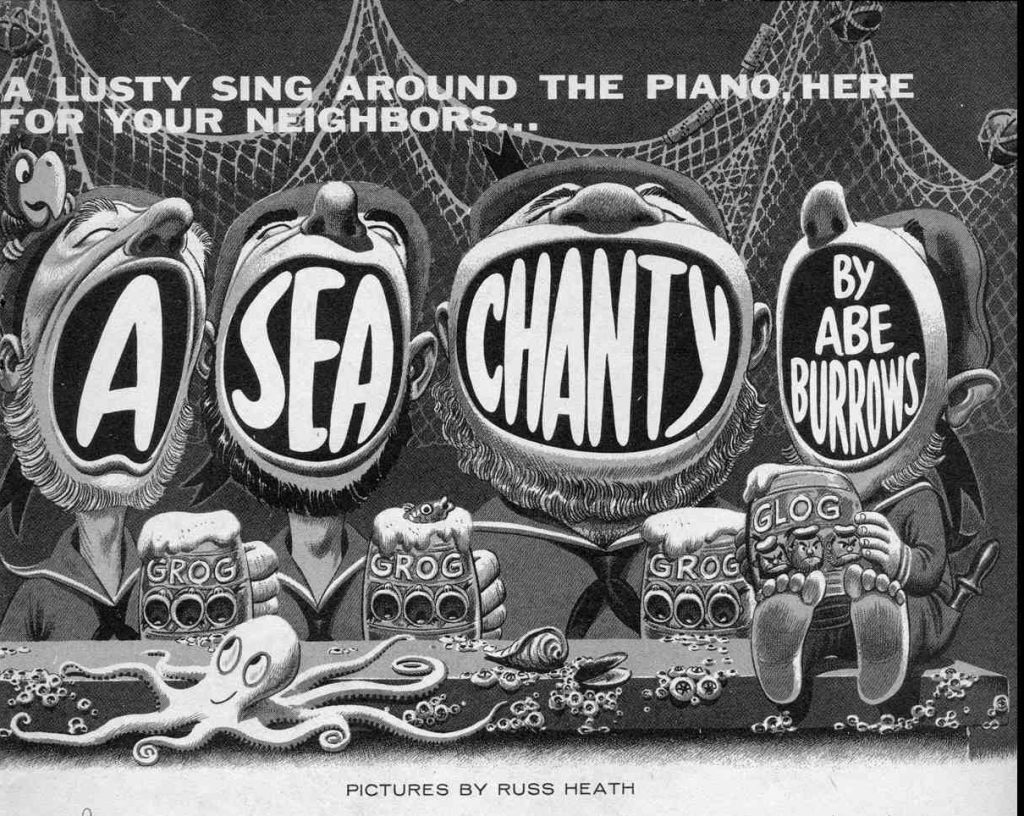

And then he left, and Davis, Elder, and Wood — the core of his “Usual Gangs of Idiots” — would eventually follow. Feldstein was able to ease through the transition by continuing Kurtzman’s tradition of guest articles by simpatico celebrities, This year alone, they included a song by future Tony and Pulitzer winner Abe Burrows and articles by onetime voice actor and comedy-record star Stan Freberg and Ernie Kovacs, a regular reader who introduced Mad-style surrealism to the infant television medium. But that wasn’t enough. Mad needed a new figurehead.

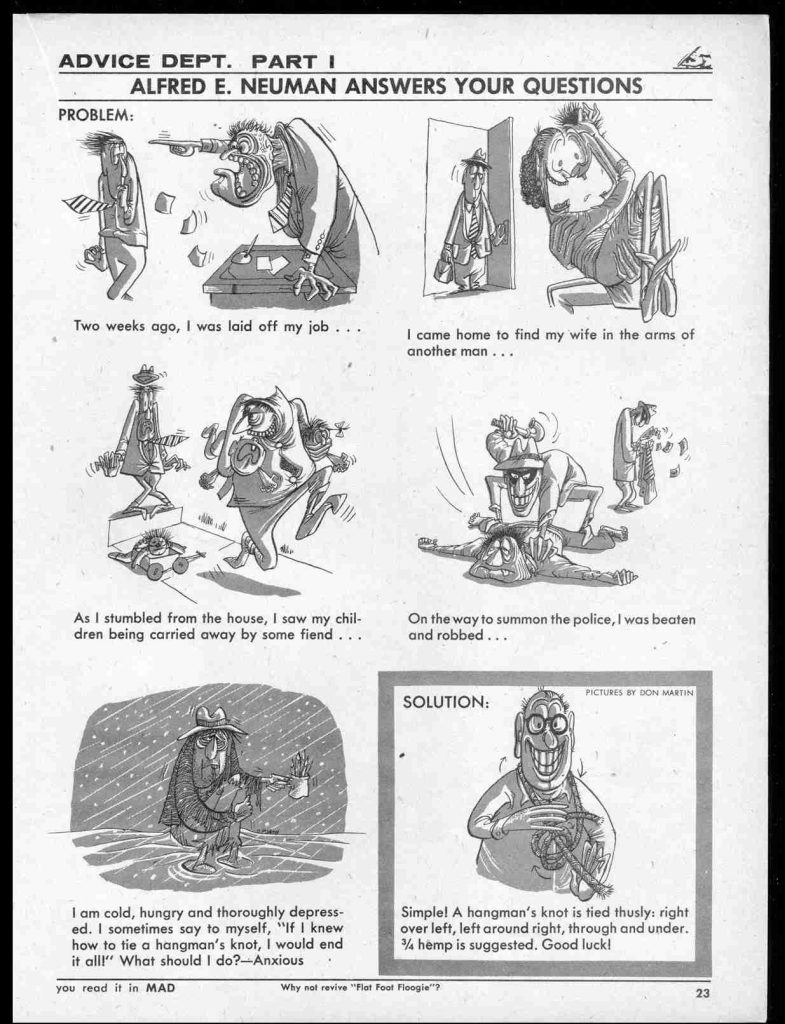

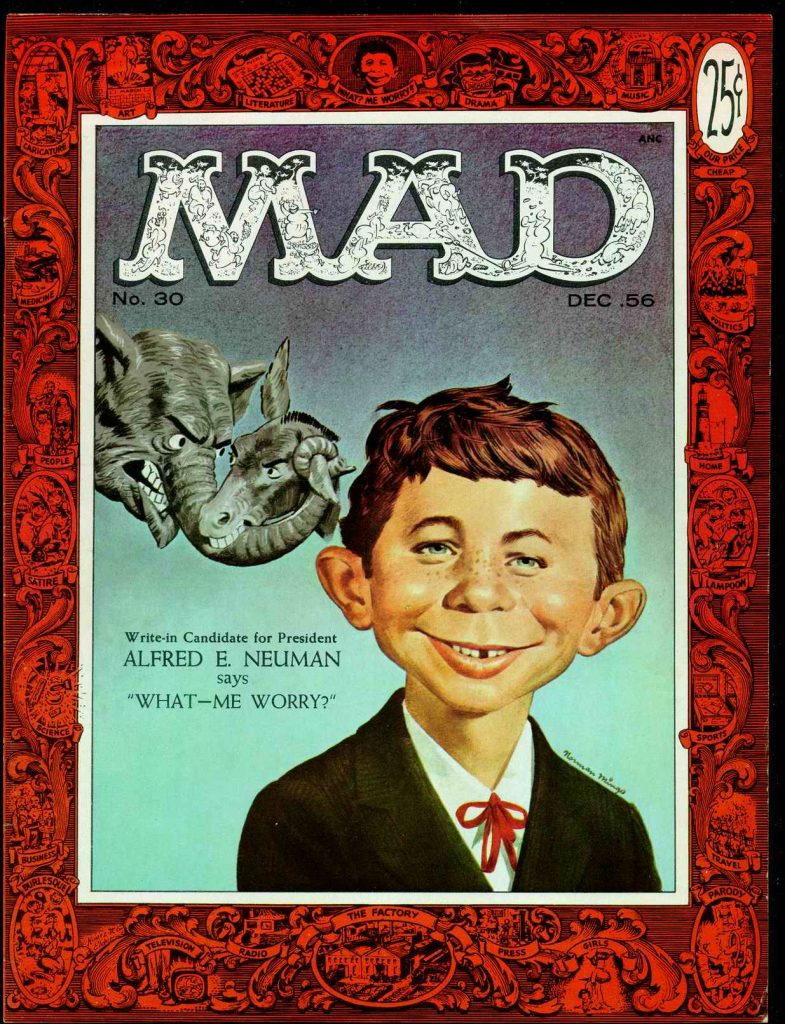

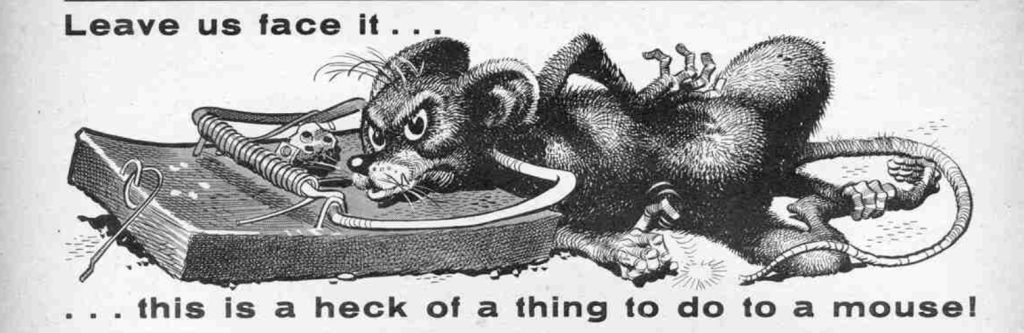

Enter Alfred E. Neuman. The face came from a postcard Kurtzman found on a coworker’s bulletin board, along with the slogan “What, Me Worry?” Both made their way into Mad beginning with the cover to the previous year’s #21 and eventually into Elder’s elaborate border for the new, magazine-sized Mad. The name had been one of EC’s many running in-jokes; in addition to all the Neumans hanging around Mad, it was the standard “Alan Smithee” credit in the Picto-Fiction books (see, I told you we’d get to that!). Among other cases, there’s the “Alfred E. Neuman Answers Your Questions” column by Mad’s rising star Don Martin with a very different design for Alfie. This one is especially beloved, even if I can’t help thinking it telegraphs the punchline too obviously (all they needed to do was swap “tie a hangman’s noose” for “end it all”).

The name and face finally came together with the final cover of the year, and that’s where they’d stay for nearly every cover of the next six decades.

Mad eventually found its voice without Kurtzman. Like other magazines, it started leaning on familiar recurring features — the Fold-In, Spy vs. Spy, The Lighter Side. And it accumulated a new Usual Gang of Idiots to replace the classic EC crew (some of them recruited from the Kurtzman-era B-team) even if only a few of them rose to the heights of their predecessors — Martin, Antonio Prohías, Sergio Aragonés, Mort Drucker, Al Jaffee, Dave Berg, and the rest.

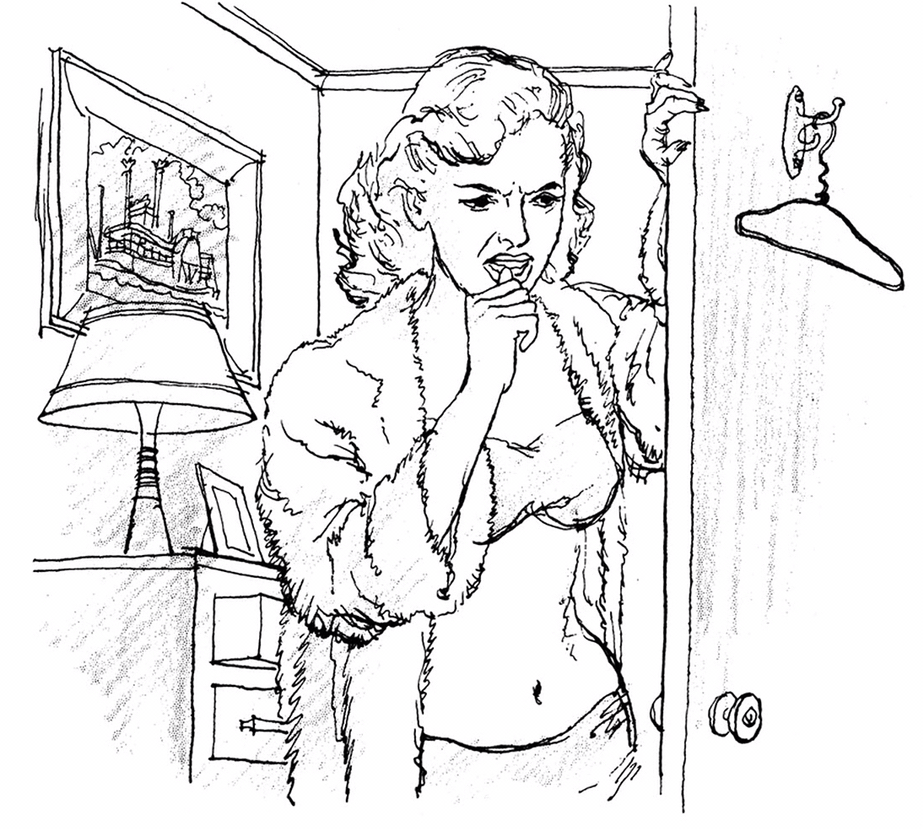

The first few issues of post-Kurtzman Mad are still funny, but some of the bite seems to be gone. To be fair, it was probably overstated from the beginning. Kurtzman’s anarchic, all-encompassing satire has been credited for the youth movements of the ‘60s, when the kids raised on his comics grew up. But it’s lost some punch in the intervening years. It’s hard to look like much of a rebel when your gender and racial stereotypes align so closely with The Man, and there’s plenty of Boomer Humor clichés that were played out even at the time — nagging wives and mother-in-laws, sexy secretaries, and so on.

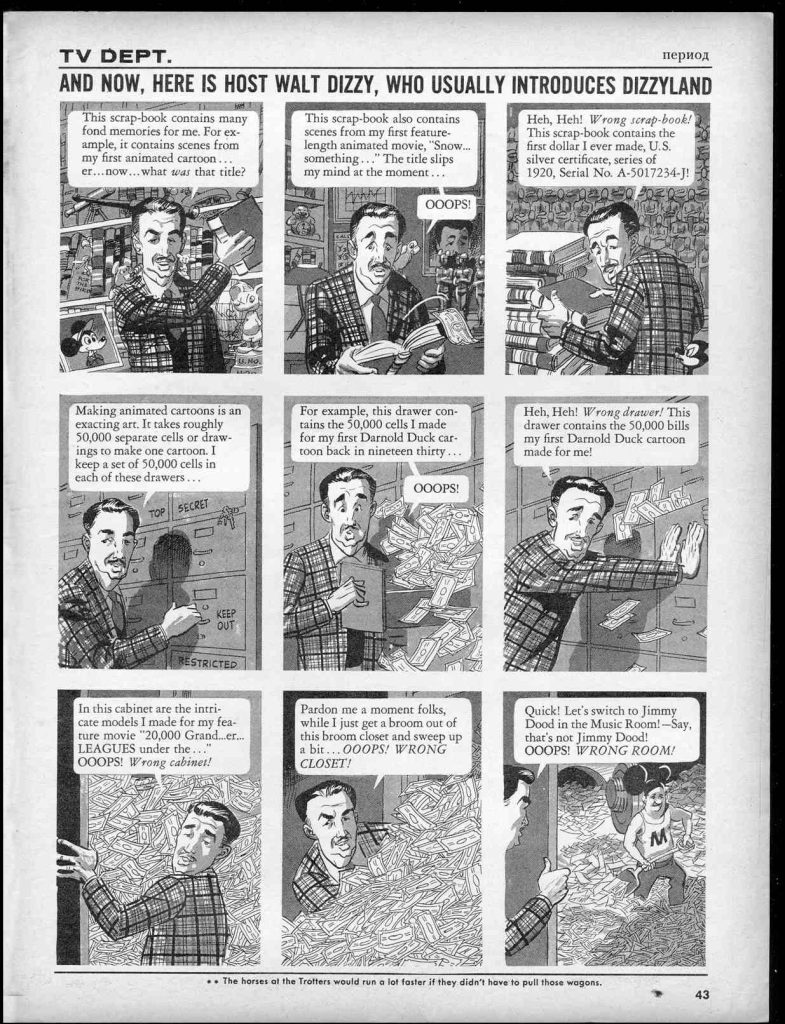

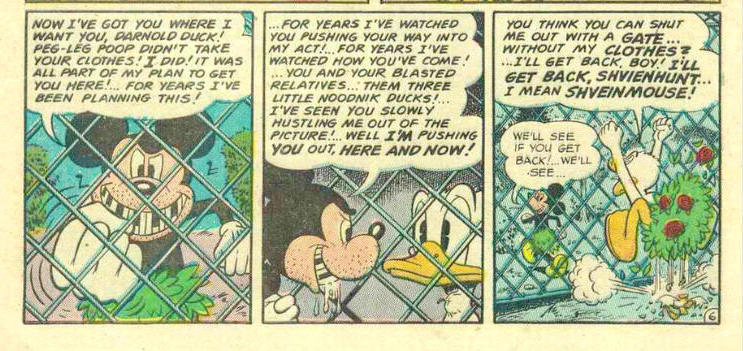

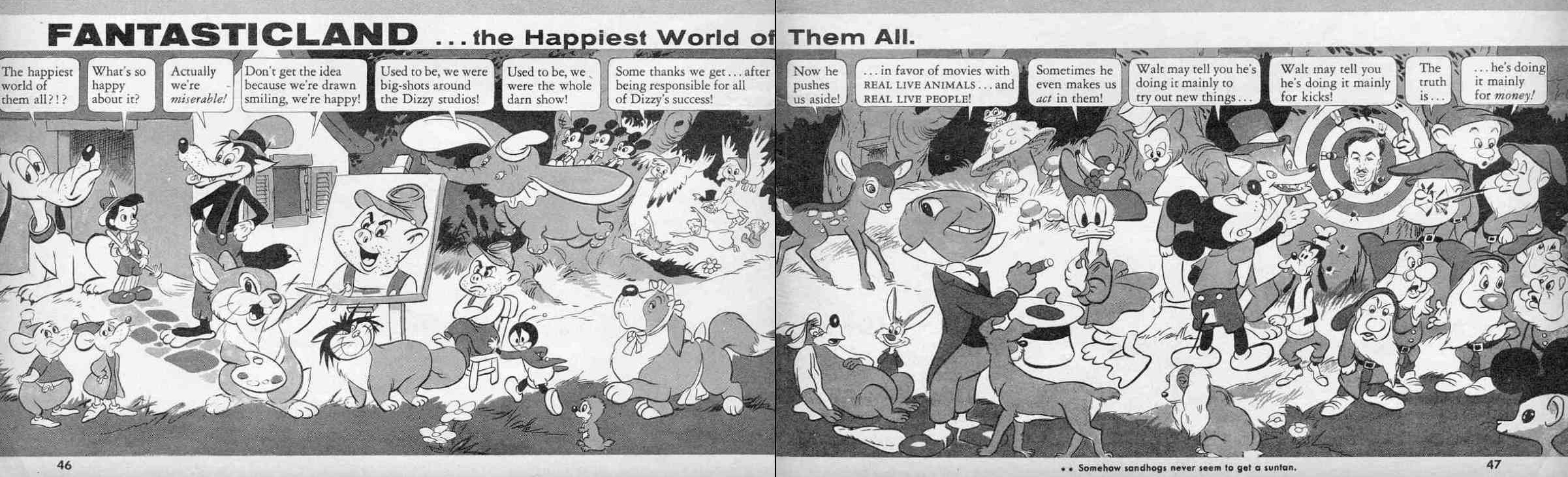

But even after all that time, there’s still something edgy and dangerous about Kurtz-Mad that up and left as soon as he did. Compare Feldstein and Wood’s Dizzyland parody — ho ho, that Walt Disney, he sure loves money! — with Kurtzman and Elder’s “Mickey Rodent” the previous year, which turned Disney’s beloved childhood merchandise opportunities characters into violent backstabbing narcissists, with a pitch-black twist ending worthy of Tales from the Crypt.

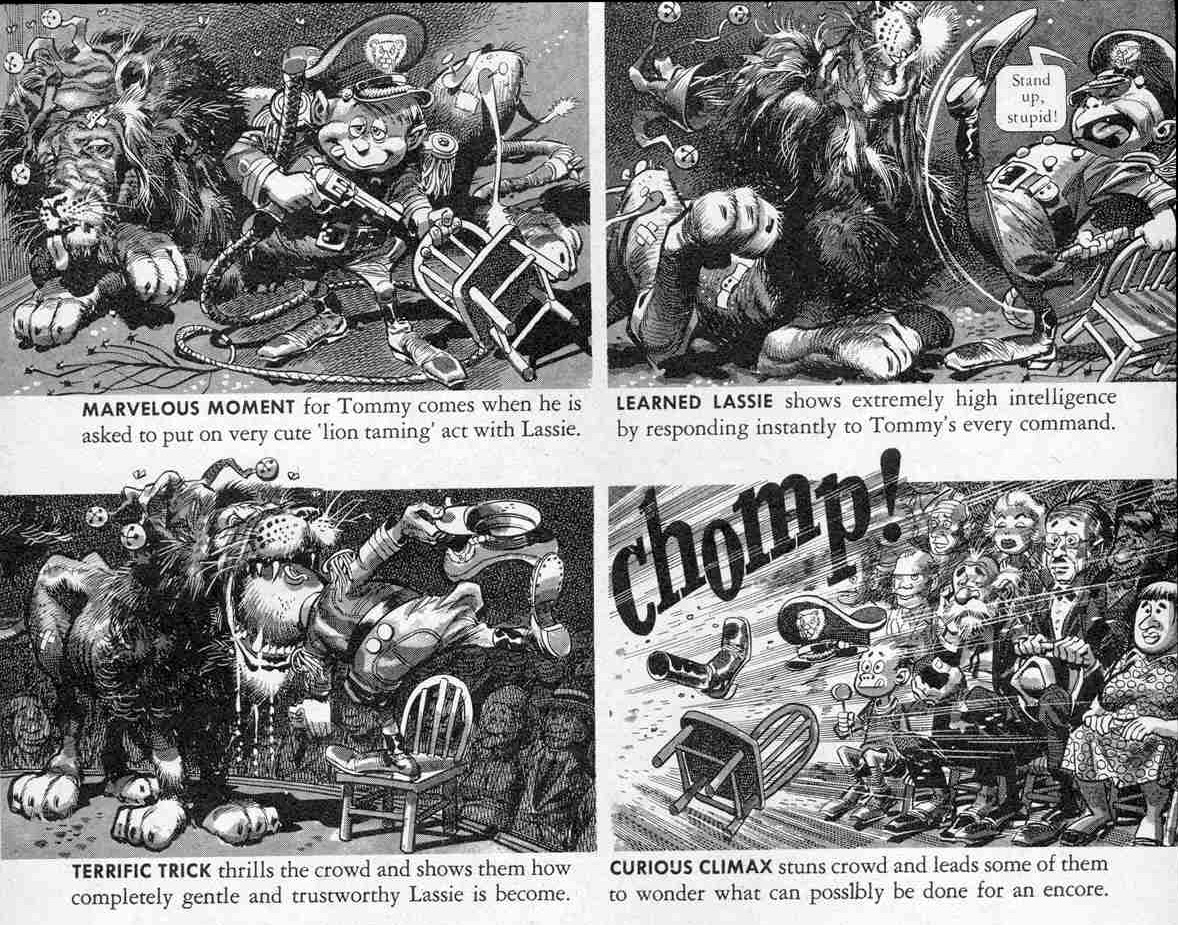

Comparing it to Mad‘s more immediate past alone, “Dizzyland” is pretty weak stuff compared to a parody of heartwarming animal stories that ends with a child getting his fucking head bit off, or the surreal gallows humor of Kurtzman’s take on a different type of MAD.

It wouldn’t be long before Mad settled into stodgy middle age, spending most of its time mocking the hippies and rebels it may have created (as this margin note shows, they were already well on their way).

At least “Dizzyland” shows Wally Wood apparently rehearsing for his infamous “Disneyland Memorial Orgy” poster (content warning: it’s not all consensual).

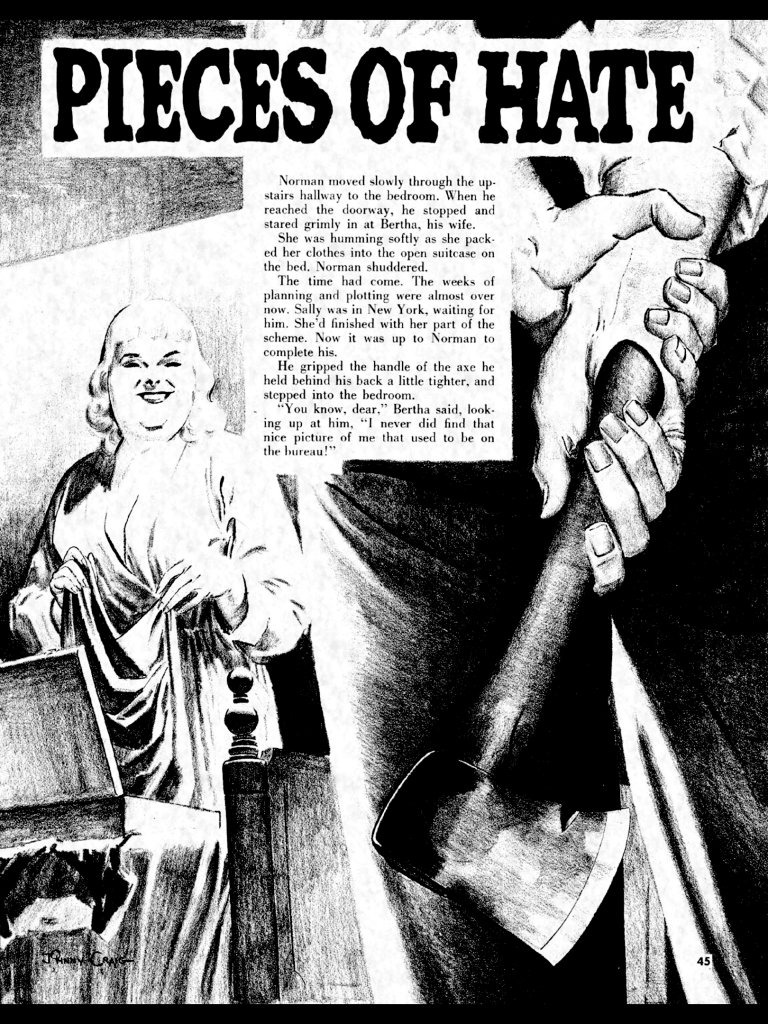

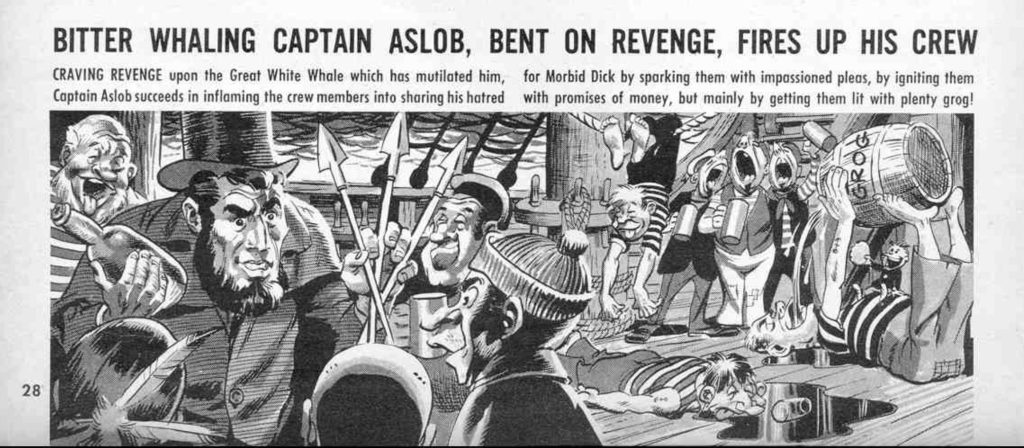

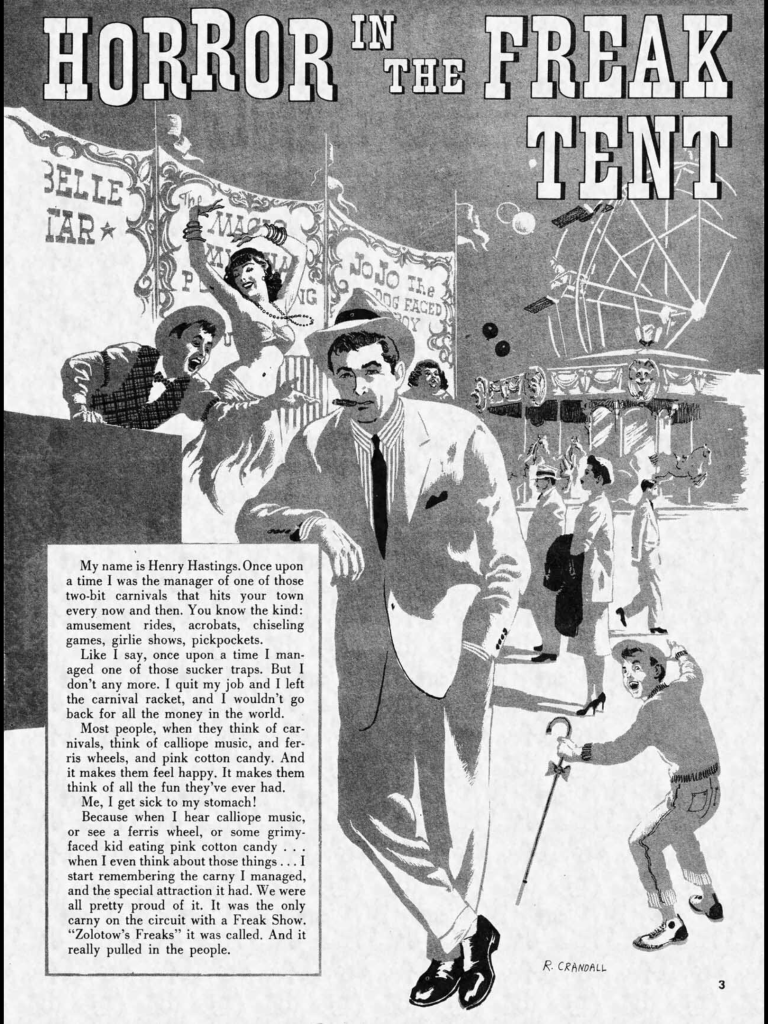

Most of the EC staff landed on their feet. Graham Ingels, whose non-horror art never looked quite right, was starved for opportunities in a post-Code world, but Al Williamson, Reed Crandall, and Johnny Craig would all find a new home at Tales from the Crypt’s spiritual successor, Creepy. Joe Orlando would become an editor at DC, reviving some of the EC spirit through its horror line. Kurtzman’s Trump flopped, but he tried again with Humbug before he and Elder settled into a steady gig at Playboy with Little Annie Fanny, with Kurtzman flying solo for his pioneering long-form paperback anthology Harvey Kurtzman’s Jungle Book in between.

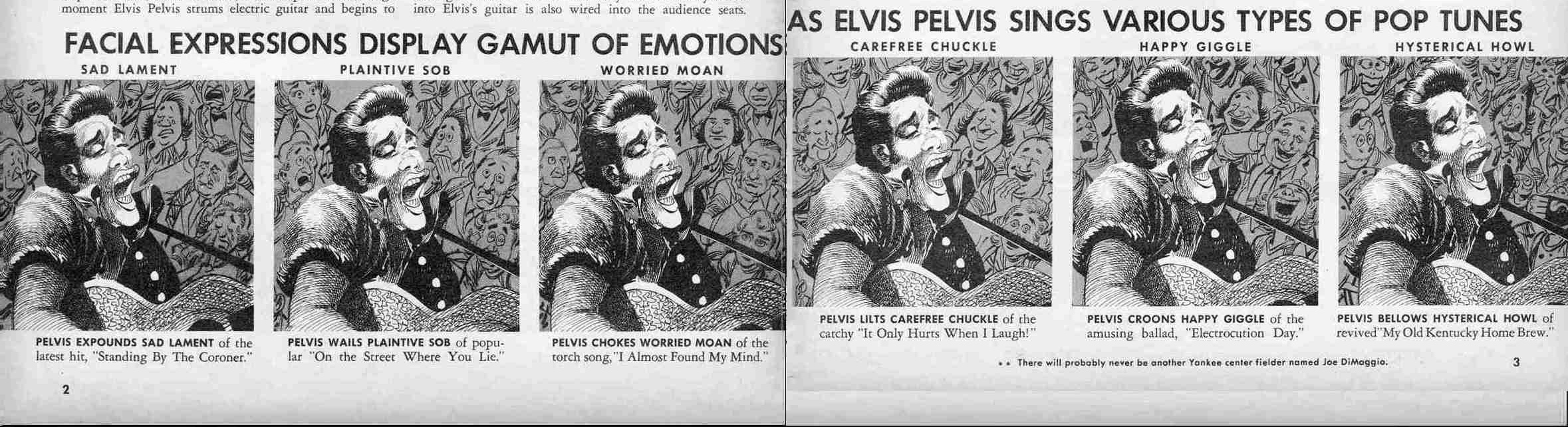

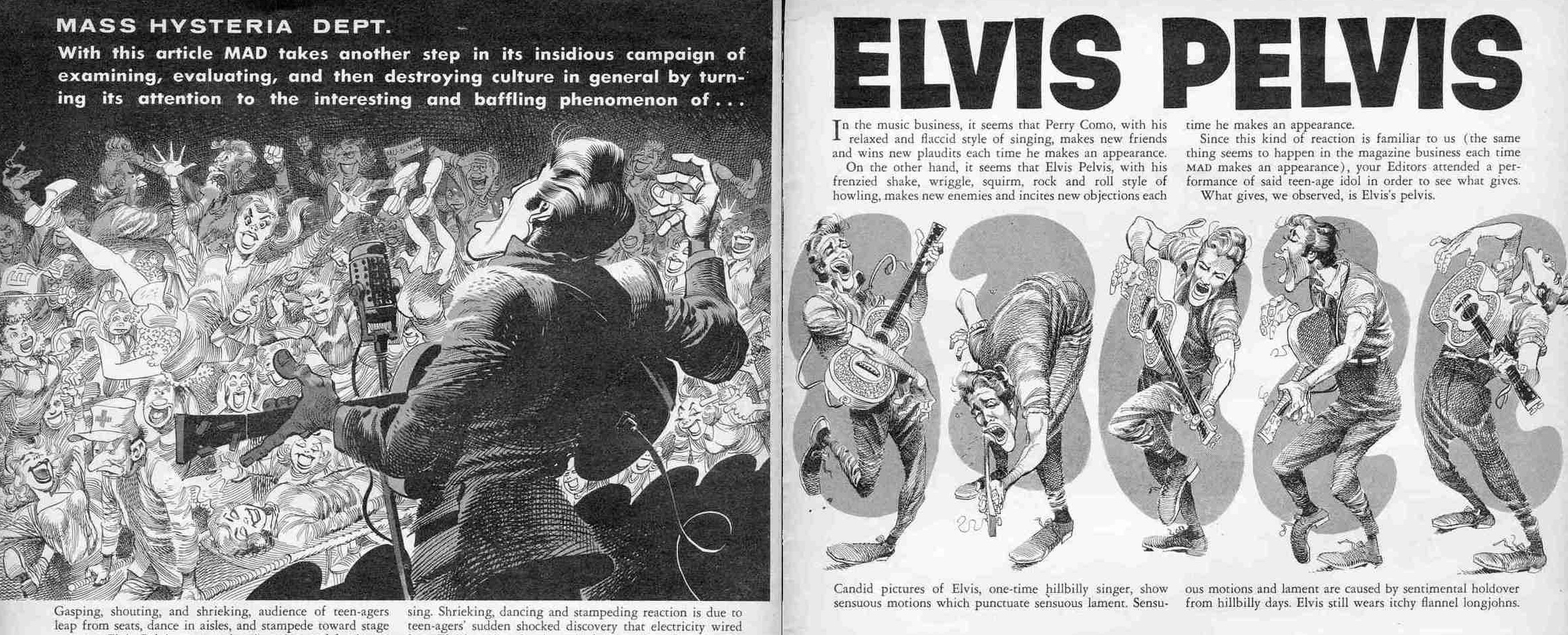

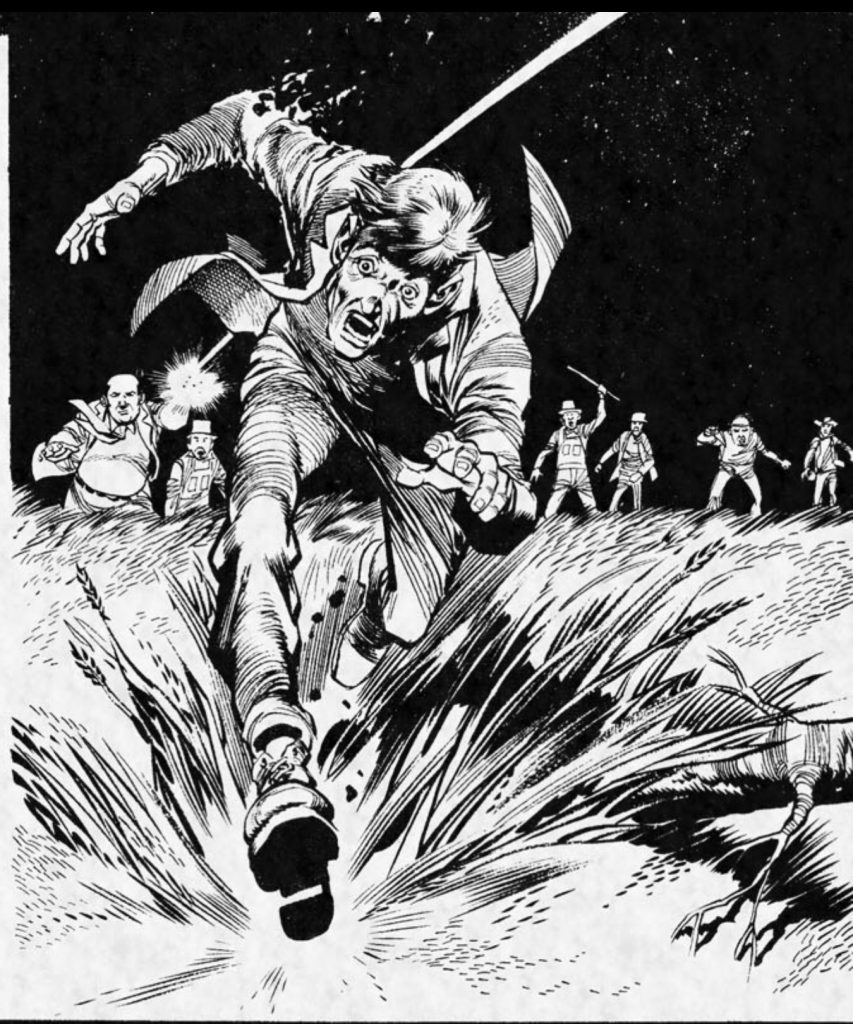

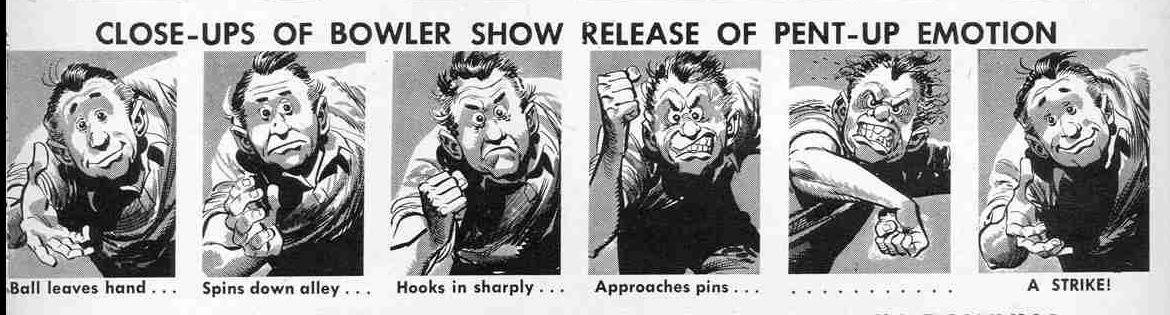

Williamson applied his trademark textural style to the Star Wars newspaper strip with Creepy‘s Archie Goodwin, and he took over his idol Alex Raymond’s creations Flash Gordon and Secret Agent X-9 before easing into retirement as one of Marvel’s most reliable inkers. Wood found steady work on everything from erotica to superheroes, and he’d follow Kurtzman’s lead in establishing an ambitious magazine to showcase his old colleagues and promising newcomers with the sadly short-lived Witzend. And if Davis was on his way out the door on Mad on his way to becoming one of America’s biggest commercial illustrators (the Animal House and It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad, World posters? All him), he at least went out on top with this art for “Bowling” and “Elvis Pelvis.”

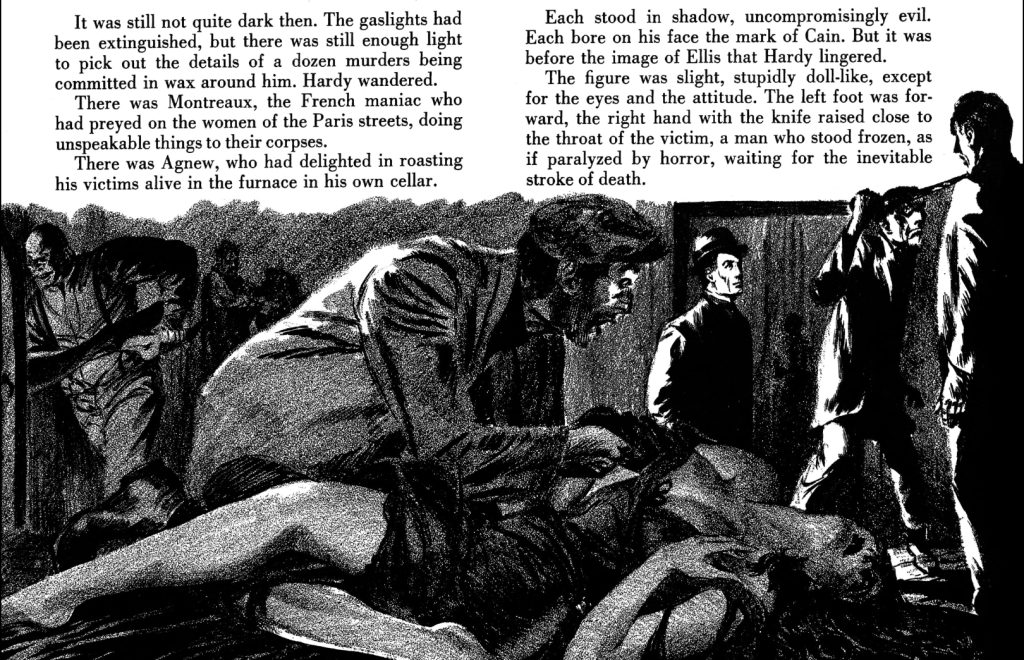

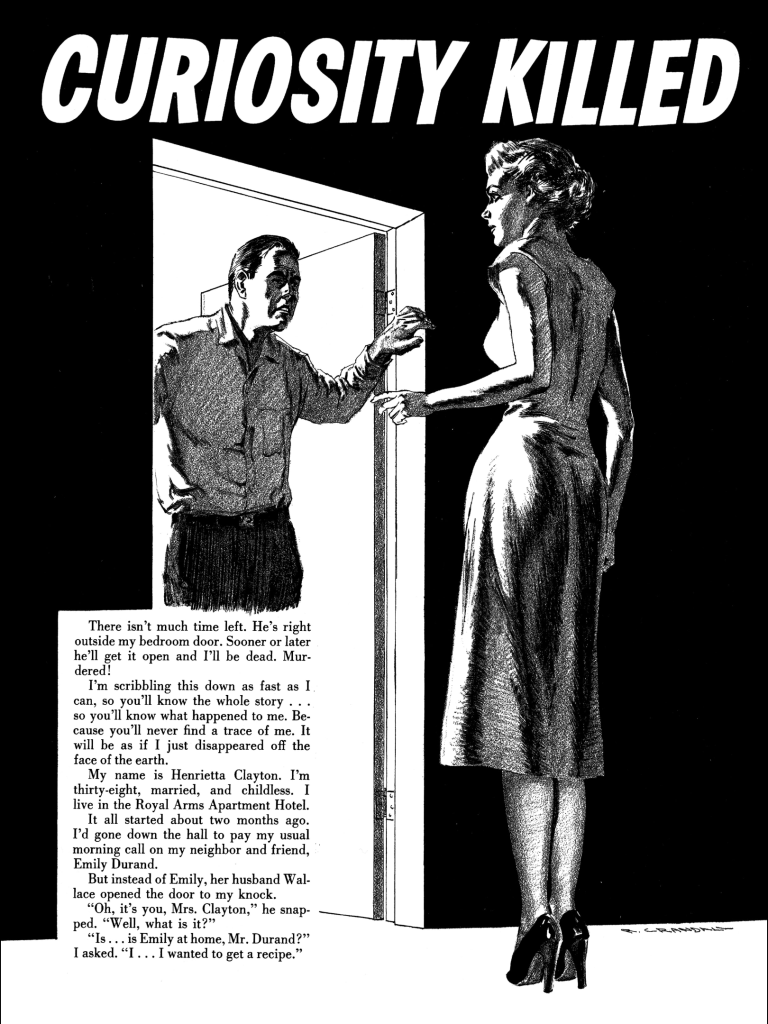

Davis wasn’t alone — even on its last legs, all of EC’s art is so good there’s no better way to wrap things up than just letting it speak for itself.

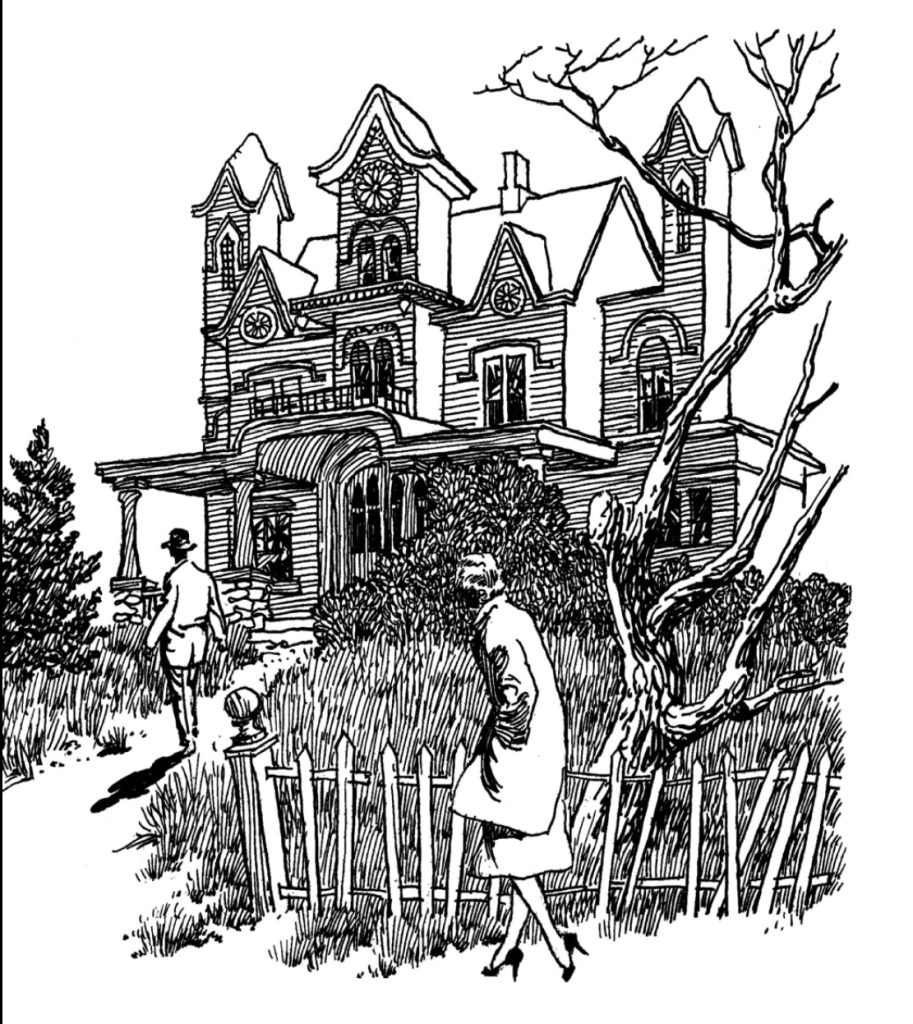

Al Williamson:

Russ Heath:

Wally Wood:

Wally Wood:

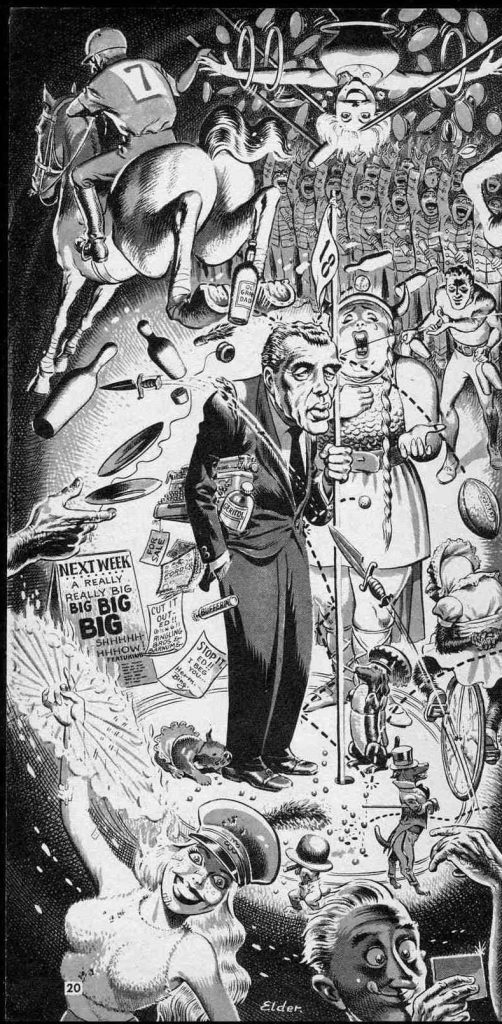

Will Elder:

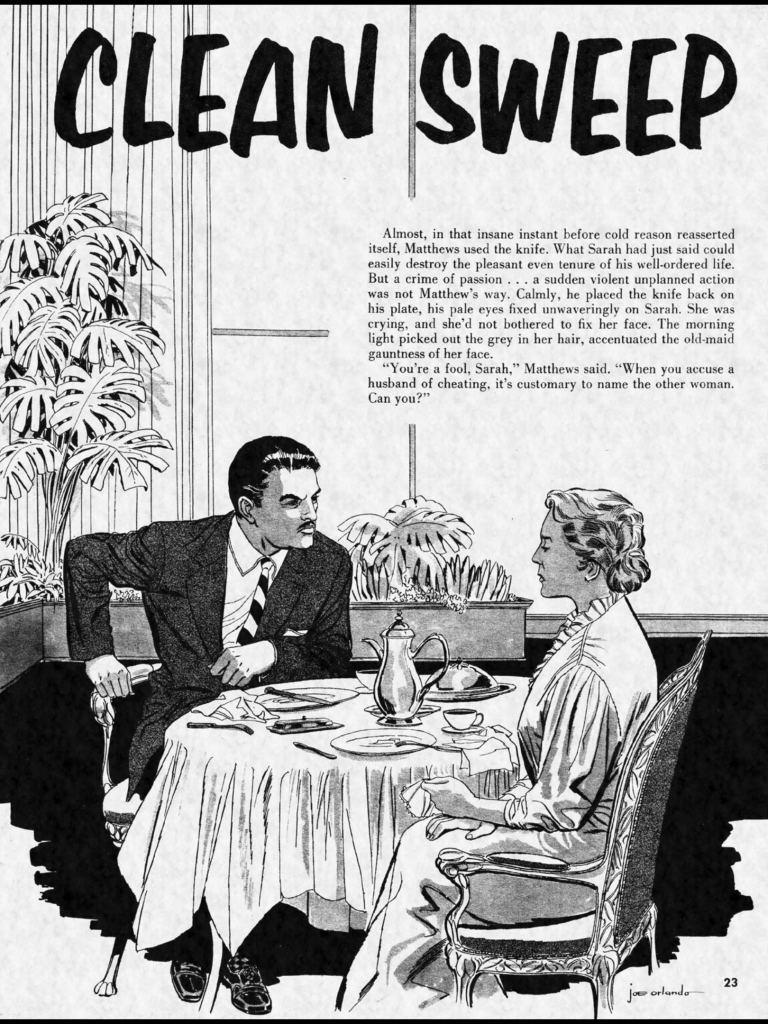

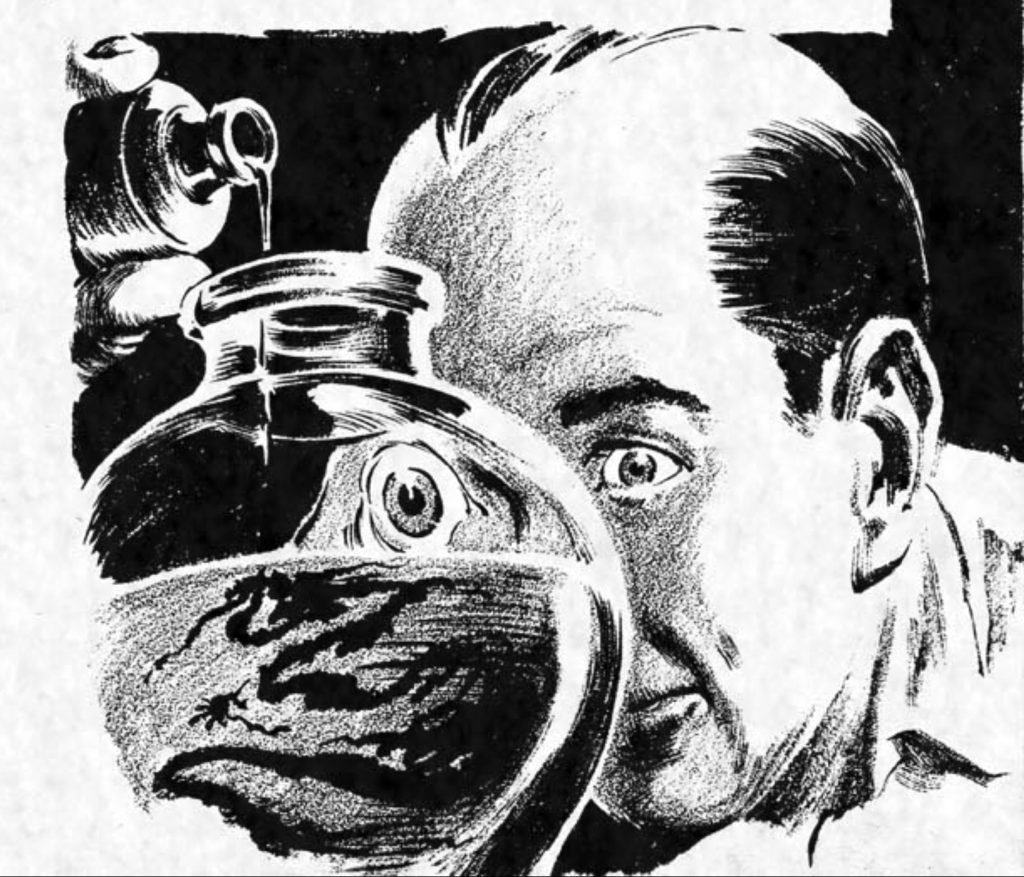

Joe Orlando:

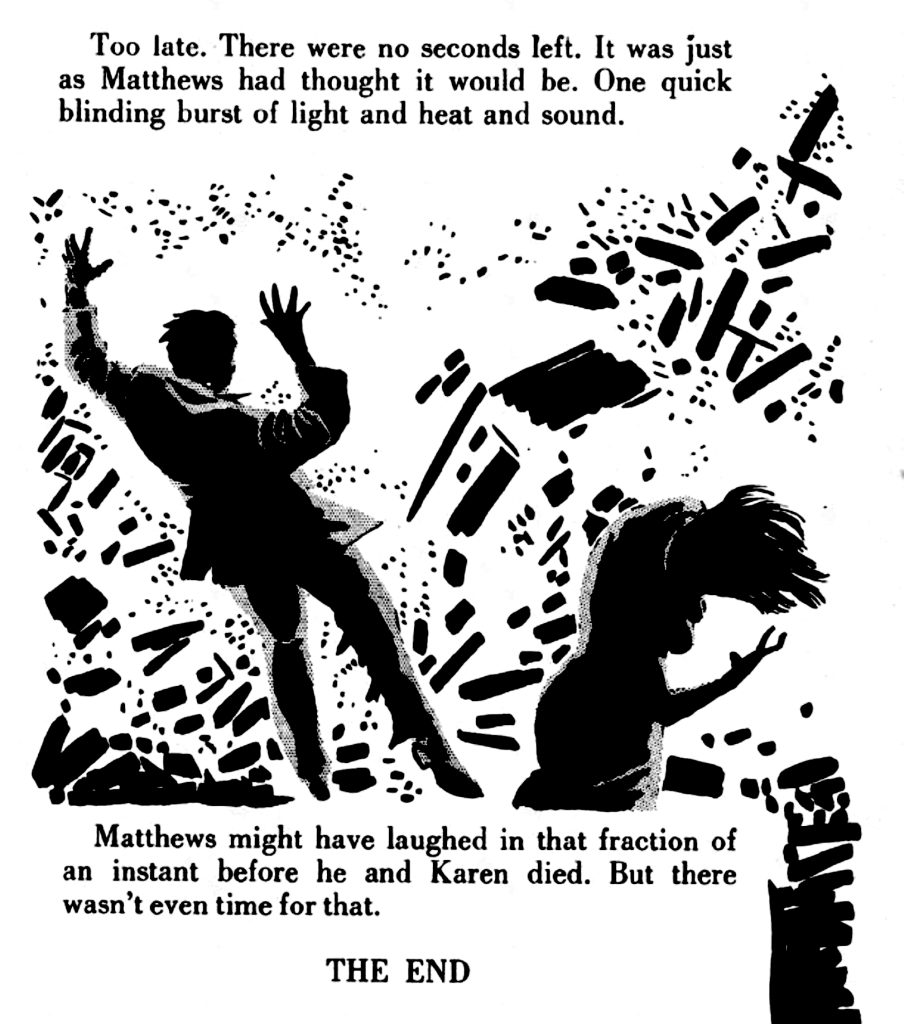

Joe Orlando:

And, once again, Reed Crandall:

The stories discussed in this article were originally printed in Mad #27–30, Confessions Illustrated #1–3, Adult Tales of Terror Illustrated #2, Crime Illustrated #2, Shock Illustrated #2–3 (and the unpublished #4), and Incredible Science Fiction #33. Shock, Crime, Terror, and Confessions Illustrated and Incredible Science Fiction are available in Dark Horse Comics’ EC Archives. The Mad issues (and some of the others) are available on Archive.org.

For more on the junk science that inspired the Comics Code, you can read Gillianren’s series on Seduction of the Innocent