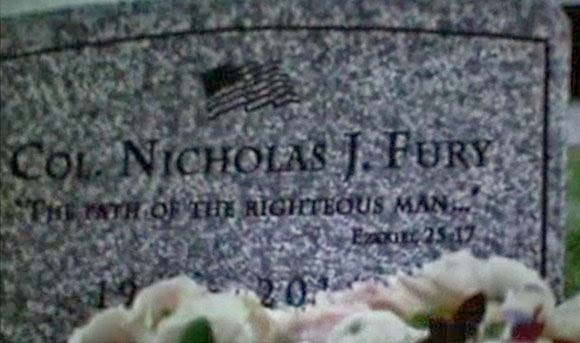

Can you believe it’s been twenty years since Pulp Fiction was released? Is there anything that hasn’t been said or written about it in those twenty years? I for one have been curious about what Samuel L. Jackson’s Jules has been up to in the two decades since he decided to quit the life after delivering to Marsellus Wallace a briefcase containing the Holy Grail, the Maltese Falcon, and a golden ticket to Willy Wonka’s factory. (At least, that’s a theory that I’ve been working on; I haven’t heard back from Quentin’s people as to whether I’m right. I’m right, aren’t I?)

From what I’ve been able to tell, in the years that he has been walking the earth like Caine from Kung Fu, Jules has transcended the mortal plane and now resides in all of us. Certainly, watching Pulp Fiction for the first time in years, I had a shock of recognition, realizing that a young musician I sometimes work with is, in his mannerisms and sense of cool, the image of Jules in his lighter moods. (And I don’t know, maybe he’s a mob enforcer on the side: I’m not with him all day, you know?) Is it deliberate? Has he sat down and memorized Pulp Fiction, like so many intense young men did back in the ‘90s, quoting Jackson’s performance so often that it becomes second nature to imitate him? Or is Jules such a pervasive pop culture presence that this young guy absorbed his attitude through osmosis? Or did Tarantino know someone like this or otherwise authentically channel a certain type of streetwise joie de vivre? In the case of my friend, it’s probably some combination, but the point is that Jules is with us to stay, and his shit would be totally chill if it weren’t for all the motherfucking snakes on this motherfucking plane.

I liked Pulp Fiction when it was released; I didn’t go back to the theater multiple times to see it, and I didn’t start wearing skinny black ties and striking gangster poses, but I admired its audacity. For example, it’s a ballsy move to open your film with a dictionary definition, like a middle schooler’s book report. Beneath the snark, however, Quentin Tarantino does come off as the brightest student in the room, always eager to show off what he’s learned from past masters and able to bend the rules to get away with whatever stunt he’s pulling today. That sense of showmanship is what drew many fans to Tarantino, and it’s the same thing that can make him hard to take after a while. The audience member who reportedly cried “Scandale! Scandale!” when Pulp Fiction won the Palme d’Or at Cannes was probably more validation for Tarantino than any award.

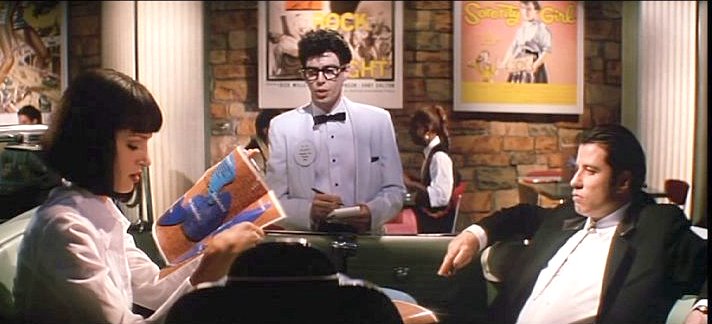

Watching Pulp Fiction now is a trip back in time, to a long-gone era when people smoked indoors and a five-dollar milkshake was considered outrageously expensive. Of course, few people were ever as effortlessly cool as John Travolta’s Vincent Vega and Uma Thurman’s Mia Wallace are in this film, and in a way they’re putting on an act as much as the waiters and waitresses dressed as Buddy Holly and Marilyn Monroe. Lest anyone think that Jackrabbit Slim’s, the Hollywood-themed home of said milkshake and celebrity-impersonating waitstaff, is an exaggeration along the lines of sitcom fast-food restaurants in which employees wear hats shaped like the tasty burgers they sell, I can attest to the reality of this kind of place, and not only in cities full of aspiring actors. The memory of a hyperactive waiter dressed as Robin the Boy Wonder, leading a conga line around a salad bar built into the hood of a ’57 Chevy, is one burned into my memory, a good year or so before Pulp Fiction; at least we didn’t have Facebook and Instagram back then to immortalize such instances of what David Foster Wallace memorably called “managed fun.” Thankfully, Pulp Fiction cuts away from Jackrabbit Slim’s Twist contest before anyone less cool than Travolta and Thurman gets a chance to embarrass themselves.

I kid: obviously, the engagement Tarantino’s characters have with pop culture is only part of their appeal. The “Royale with cheese” and “Fox Force Five” have entered public consciousness and inspired parodies and homages, and at the time it seemed like a breath of fresh air to have movie characters acknowledge the same cultural markers the rest of us live with, but the novelty of such conversations would wear thin if the characters weren’t so boldly drawn and brought to life by the cast. There are life-or-death consequences to their actions: poor Vincent Vega would seem to be a victim of bad luck, but the 360-degree view we get of him throughout the film shows that there’s a fine line between “effortless cool” and “idiotic carelessness.”

Butch Coolidge (Bruce Willis), the agent of Vincent’s downfall, is the closest thing the film has to an everyman, but he’s working his own angle, too, and he wouldn’t have even been in the same apartment as Vega if it hadn’t been for his watch, the importance of which is footnoted in Christopher Walken’s movie-stealing monologue. There are genuine shocks: the first time we saw Butch and Wallace trapped in the pawn shop and heard the phrase “Bring out the gimp,” we were all like, “Whoa, what the–!? Like, I don’t even,” although we weren’t quite that articulate in expressing our reactions. The twisty storylines and tangled chronology don’t feel like a gimmick—or, at least, it’s a gimmick that’s a lot of fun to get swept up in.

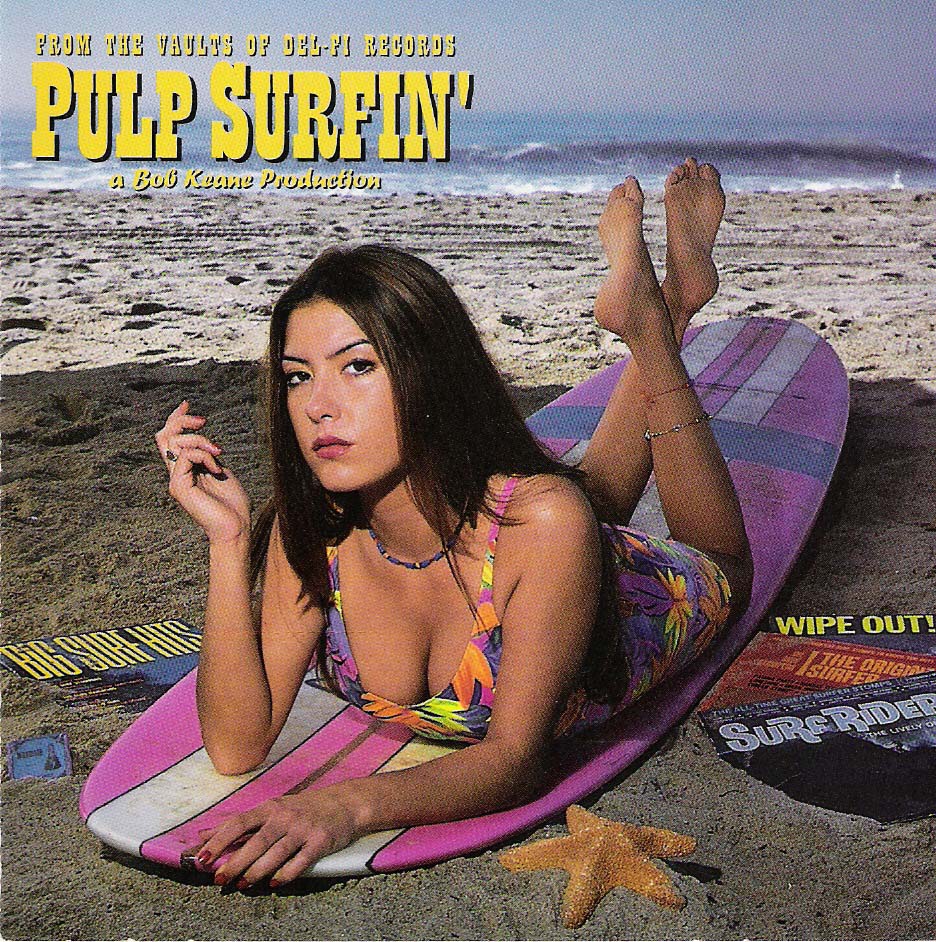

Pulp Fiction’s glamorous, menacing combination of Old Hollywood character types and New Hollywood explicitness was hugely appealing; there were other movies released in 1994 that had a more direct effect on me personally (Ed Wood and Crumb, if anyone cares), but I was very sympathetic to Tarantino’s urge to make high art out of shopworn genre tropes, turning them inside out and finding new ways to breathe life into them. The often-parodied poster of Uma Thurman lying on a bed covered with brightly-colored pulp magazines, an image that doesn’t even occur in the film, sums up both that impulse and the way Tarantino’s characters became icons.

As I said, I didn’t immediately start writing screenplays about smart-mouthed gangsters and their surf-guitar-loving mamas, but Tarantino’s storytelling methods made an impression on me. Everybody in Pulp Fiction wants something: obviously, motives are important in fiction, and conflict is desirable for drama; there’s nothing new about that. But for me, it was an important step up from we’re-all-on-the-same-team good guys and bad guys. It invited me to think of motive and story structure in more complex ways. Pulp Fiction dramatizes our habit of making ourselves the lead of our own movie, while clearly illustrating the ways none of us are in complete control of how that story unfolds.