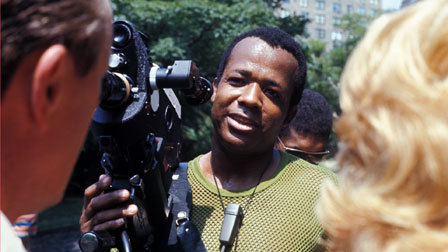

When I heard that African-American filmmaker William Greaves had died last week, I wanted to revisit this film, shot in 1968, that remains a challenging vision of the multiple, and at times conflicting, identities of the filmmaker. Greaves, while taking on the roles of writer, director, and producer, also becomes an actor in the film: cameras not only film the action; they film the film crew—and Greaves—filming the action, and anything else of interest around the shooting location.

At the time of filming, Greaves had made Still a Brother: Inside the Negro Middle Class for PBS, while also having taken over the leadership of the monthly National Education Television program, Black Journal. Building off of a documentary approach, mixed with fiction and a theoretical overlay, Symbiopsychotaxiplasm has affinities with the formal experimentation of Medium Cool (1969), written, directed, and produced by Haskell Wexler. Medium Cool takes its title from media theorist Marshall McLuhan’s idea that television is a “cool medium” that requires greater audience participation than a “hot” one. This idea becomes politically charged: after including, as part of the narrative, footage of the riots during the 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago, Wexler, in the last shot of the film, turns his camera on the viewer.

Symbiopsychotaxiplasm, however, has no noticeable climax; its setting in Central Park—at first—seems removed from political conflict. The film takes its title from social-science philosopher Arthur Bentley’s concept, symbiotaxiplasm, that proposes that people and their environments are connected. Greaves inserted “psycho” into the term because he felt the psychological dimension was particularly relevant for filmmaking.

Turning critical attention to the filmmaking process, Greaves filmed repeatedly the same scenes performed by different actors. The deliberately badly-written script, containing at times a barely-concealed homophobia, foregrounds the emotional wreckage of a failed relationship between a man and woman. Thrown off-balance, the film crew responds to Greaves’s provocations—his acting incompetent and arrogant—by filming their own discussions, many which focused on the flaws they saw in the film. Needless to say, the crew wondered what Greaves would make of their intervention when he saw the footage.

Greaves’s decision to include this footage in the final cut discloses a conflict between collective and individual perspectives in filmmaking. If Wexler uses the filmmaking process to expose the repression directed against underground movements, Greaves suggests that such repressive control can emerge from inside socially-conscious films—even films, such as Symbiopsychotaxiplasm, that do not directly reference social issues.

The sequel, Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take 2 1/2 (2002), was made with the help of Steve Buscemi and Steven Soderbergh, who whole-heartedly embraced the artistic challenge of Take One. Greaves, this time, does not try to provoke the film crew. Rather, the script draws on the past lives of the man and woman in Take One, as if to suggest the discomforting pressures of history. In the last shot, the crowd noise from the finish of the New York marathon that just happens to be taking place very near the filming location is heard over the silent images of the actors. Another reminder of the influence of environment on the filmmaking process—yet another provocation from Greaves.