Directed by Jean-Luc Godard, A Woman Is a Woman (1961) could not be a better fit for this series. It plays with conventional meanings found in the musical genre like a cat with a ball of yarn. The premise is outright comic—wanting more than anything to have a baby, a young woman asks the man she loves to assist her; after he turns her down, she turns to his best friend—yet Godard openly questions its originality, saying it could have been done by Ernst Lubitsch. Tragedy and pathos surface throughout, and there is little traditional singing and dancing at all.

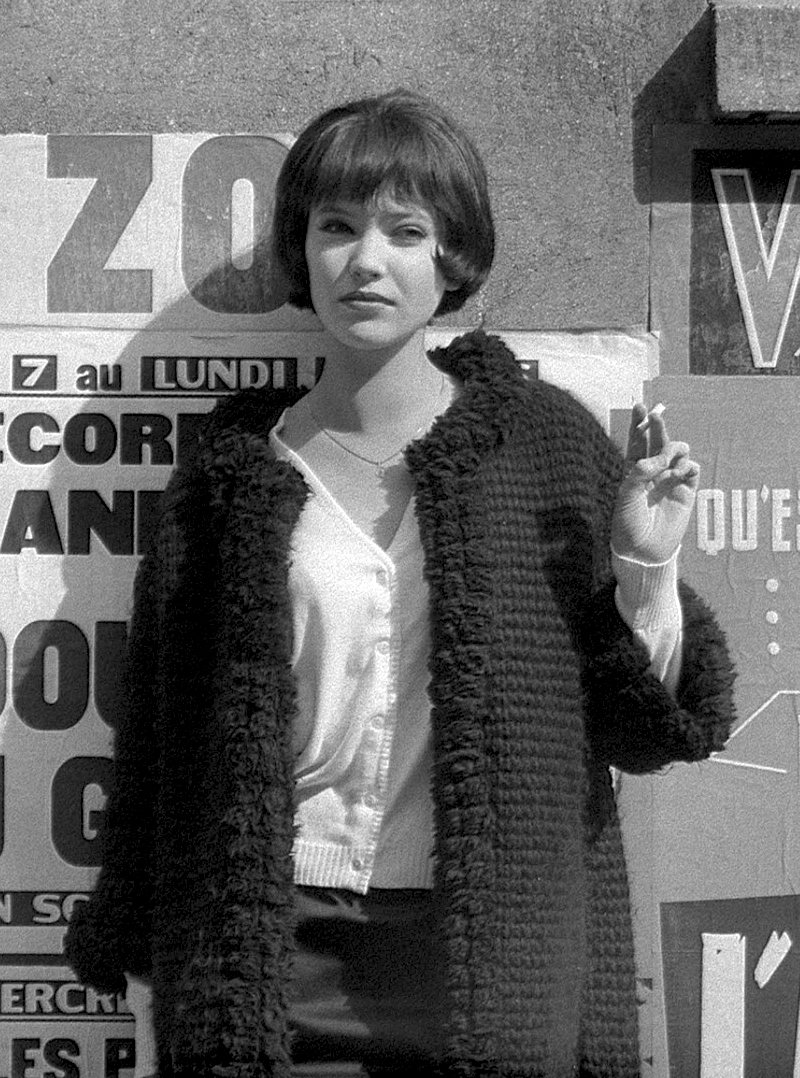

Just as the film unmakes the musical, it questions, like Vertigo (1958), the desires we long to see projected on screen. The perfect object of masculine heterosexual love, Anna Karina plays her obsession about baby making in a way that borders on creepy. Her lover’s best friend, played by Jean-Paul Belmondo, who came to the world’s attention after his breakout performance in Breathless (1960) is off in a movie star dream world. Jean-Claude Brialy, as her lover, appears somewhat more levelheaded, having a book selling job.

The film opens with “Lights, camera, action!” It’s a self-conscious reference if ever there were one. But the narrative seems more about reaction; there is a constant focus on what Karina wants (echoing the Freudian question: what do women want?). Belmondo and Brialy take turns pursuing Karina, drawn to the fantasy she projects like the patrons at the club where she works as a striptease artist.

Godard filmed the exteriors in one of the most commonplace areas of Paris, as if to magnify the distinctions between reality and fantasy. The actors wore their own clothes as if they could more easily enter and leave the stage. The apartment on set even had a front door which Godard closed and locked every day at the end of filming.

All of the performances are inseparable from the performers. Belmondo looks and acts like he’s reliving scenes from Breathless. Karina, who would soon marry Godard, is filmed, at times, as if the camera, directed by Godard, is also pursuing her; Brialy stands in as Godard’s cinematic double.

Of course, anything filmed is no longer reality per se, but Godard goes further to say that any film is intertextual—that is, it relates to other films. A Woman Is a Woman makes the most (non)sense when compared with other film musicals. There are cameos from other actors in films of the nouvelle vague. But Belmondo takes it over the top, joking about being pals with Burt Lancaster, wanting to run home to watch Breathless on television, and asking Jean Moreau, who randomly appears in a cafe, about Jules and Jim (1962), a film in which she starred.

Of course, anything filmed is no longer reality per se, but Godard goes further to say that any film is intertextual—that is, it relates to other films. A Woman Is a Woman makes the most (non)sense when compared with other film musicals. There are cameos from other actors in films of the nouvelle vague. But Belmondo takes it over the top, joking about being pals with Burt Lancaster, wanting to run home to watch Breathless on television, and asking Jean Moreau, who randomly appears in a cafe, about Jules and Jim (1962), a film in which she starred.

At the same time, film can take over reality. In a 1961 interview with a French journalist, Godard said he found it funny that he could wind up men on the street by having Brialy and Karina approach them, then having Brialy ask, while being filmed, if they would like to get Karina pregnant.

Despite these narrative diversions, the relationship between Brialy and Karina heads downhill. Brialy is neurotic, jealous, and controlling (perhaps a critical self-reflection of Godard). Karina’s worldview, apart from her boundless energy and joie de vivre, is narrow indeed. Neither can relate to the other’s needs and wants: the negative side, Godard suggests, of the old adage that opposites attract.

The problem is that their problem simply can’t have a logical solution—which is proof, depending on how you look at it, of either Godard’s imagination or his lack thereof, and which will further determine whether you find the ending playful and funny or heavy handed and cynical.

Karina confesses that she’s had sex with his best friend, although we can’t be completely sure. Brialy announces to Karina that if he can get her pregnant now, he gets the right to be the father of her child. We are told, but do not see, that “the deed has been done.”

To evaluate A Woman Is a Woman, we might want to look at it in an intertextual way, as it relates to Godard’s next film. That would be My Life to Live (1962), a much darker look—shot in black and white—at the struggle of a prostitute, played by Karina, to hold onto her autonomy against the social forces that close her down.

To evaluate A Woman Is a Woman, we might want to look at it in an intertextual way, as it relates to Godard’s next film. That would be My Life to Live (1962), a much darker look—shot in black and white—at the struggle of a prostitute, played by Karina, to hold onto her autonomy against the social forces that close her down.

Viewed in this way, A Woman Is a Woman becomes a colorful flight of fancy before the sudden and intense pressure drop of My Life to Live. Godard’s deconstruction of the musical also makes a more serious point about how women in films are packaged for male consumers. It’s rarely a reciprocal process, and Godard warns us that to think otherwise would be foolish.

It’s also instructive to think about a recent film, La La Land, that tries to update and pay homage to the musical genre. Like A Woman Is a Woman, its desire to entertain the audience clashes with its attempt to critically comment on film as a vehicle for escape. As Julius Kassandorf has argued, La La Land “contains in-movie self-criticism, but is so half-hearted with it that it could be dismissed out of hand.”

I would argue, regardless of predictions that La La Land will sweep the Oscars this year, that there are better films, such as, but perhaps not limited to, Moonlight, Manchester by the Sea, and 20th Century Women. But, I think, we might be limiting our evaluation somewhat. We should judge La La Land by what its director and writer, Damien Chazelle, comes up with next. If he makes (and I sincerely hope he does) a film as powerful as My Life to Live, it will invariably change how we view La La Land.