When you think of a major influence on Woody Allen, the easy answer is Ingmar Bergman. Indeed, this influence is front loaded in Husbands and Wives (1992). The narrative arc, where a married couple in the first scene announces to their friends that they are splitting up, which causes the eventual end of their friends’ marriage, is inspired by Scenes from a Marriage (1973). In addition, the interview segments, which are used as a framing device, are taken from The Passion of Anna (1969).

But another important influence on Allen, one that tends to be overlooked, is the groundbreaking independent films written and directed by John Cassavetes. His film Shadows (1959) created the template for the walking and talking scenes in NYC that Allen further refined in Annie Hall (1979). And the conceptual bent of Husbands and Wives appears influenced by Cassavetes’s masterpiece, Husbands (1970).

In Husbands, three middle-aged married men go off on a wild four-day adventure, culminating in an impulsive trip to London, to mourn the sudden death of their close friend. What the film is really about, however, is what Cassavetes calls the “lovely war” between men and women. There’s a brutal scene where Harry, played by Ben Gazzara, physically assaults his wife and her mother, before the other two men drag him out of his house to cool off. Other than this one scene, the wives don’t appear in the film at all.

In Husbands, three middle-aged married men go off on a wild four-day adventure, culminating in an impulsive trip to London, to mourn the sudden death of their close friend. What the film is really about, however, is what Cassavetes calls the “lovely war” between men and women. There’s a brutal scene where Harry, played by Ben Gazzara, physically assaults his wife and her mother, before the other two men drag him out of his house to cool off. Other than this one scene, the wives don’t appear in the film at all.

The focus is placed on the men, whose flaws are immediately apparent, to the point where they cross the line of being likable. Cassavetes’s treatment of these men, including Gus, the character he plays in the film, has an honesty almost without precedent: we don’t really know why these characters do what they do, and no explanation is given for what their problems are. In fact, Gazzara requested that he give a speech that would help the audience understand his character. Cassavetes’s blunt replay was that if he did that, there would be no need for acting or dialogue; it could all be replaced by voice-over narration.

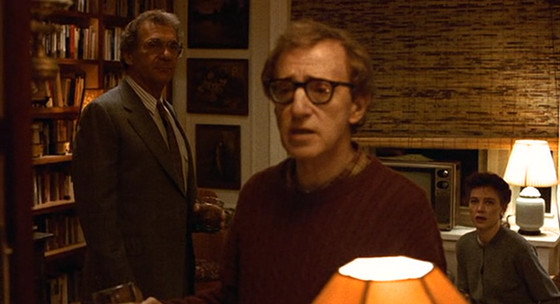

Watching Husbands and Wives, it’s fairly easy to see what Allen thinks are the middle-aged husbands’ problems—it’s their wives. I haven’t heard the label of “ball-buster” used so freely since Carnal Knowledge (1971); Allen ups the ante by creating his own descriptor: in the role of Gabe, a creative writing teacher, he says in the beginning of the film that he’s attracted to “kamikaze women.” Judy, his wife, is relatively more stable, but it turns out she’s passive-aggressive. Her former husband tells us this when he’s being interviewed.

Allen’s use of Cassavetes’s stylistic technique, open-ended scenes with dynamic and unpredictable emotional shifts, gives the film a documentary feel, as if what we’re seeing, the lives of these troubled people, is as close to reality as we could bear. Yet our reaction depends on whether we think Allen is fudging things to favor the husbands, rather than the wives.

I think on this point there are more than a few moments that are quite revealing. There’s a brutal fight between Sydney Pollack, who plays the role of Jack with a quasi-Gazzara flair, with his new girlfriend that reveals she’s as much of a ball-buster as Sally, his former wife. In this universe, men have few choices of what type of woman they can be with—and all types of women have serious liabilities.

I think on this point there are more than a few moments that are quite revealing. There’s a brutal fight between Sydney Pollack, who plays the role of Jack with a quasi-Gazzara flair, with his new girlfriend that reveals she’s as much of a ball-buster as Sally, his former wife. In this universe, men have few choices of what type of woman they can be with—and all types of women have serious liabilities.

Michael, the single guy with whom Judy sets up Sally is kind of creepy, but note how much we tend to see him from Judy’s perspective. She makes him out to be a charming drunk—when it could be argued he’s more of an embarrassing one—and describes him to Sally as quite a catch, even though he throws himself at Sally on their first date.

If earlier I noted how the way men view women does women no favors, how women view men, on the other hand, makes the men look more desirable. It’s a double-standard that plays out through the film and drives the conflict. Allen does remind us several times that none of the characters know what he or she wants, and mistakes will be made, of course.

When the battle is over, however, the winner is the one who can best lay claim to the moral high ground. The unprincipled Jack reconciles with Sally (better, I suppose, the ball-buster you know than the one you don’t). Michael and Judy are together, their relationship built on the time-honored principles—typical in Allen’s work—of misery and confusion. Gabe is the last man standing, single by virtue of having decided not to sleep with a female student who is clearly enamored with him. This decision is meant, in a rather forced way, to appear as a moment of redemption, anticipating the overblown melodrama of the middle-aged male protagonist in American Beauty (1999). Given what choices Jack, Michael, and Gabe have, they would all be, in the words of an old Tom Waits song, “Better Off Without a Wife.”

Husbands is less cynical: while Harry stays in London, his marriage presumably over, the other two men return home, loaded down with last-minute gifts from the airport gift shop for their children. Then they go their separate ways. The camera follows Gus as he walks up the driveway to his house and meets his son and daughter (played by Cassavetes’s own children). Cued by his son’s playful warning, “Oh boy, are you gonna get it!”, he gives a bemused shrug of his shoulders just as he moves out of camera range, and the film abruptly ends. Although the final scene feels ambiguous, Cassavetes later insisted that he didn’t see it as a sad ending at all.

Husbands and Wives also has an abrupt ending. Gabe, in a petulant tone of voice, asks the unseen interviewer if he can leave—come to think of it, a passive-aggressive act if there ever were one.