William S. Burroughs stated that the title of his most (in)famous book, Naked Lunch (1959), defined “a frozen moment when everyone sees what is on the end of every fork.” A visionary chronicle of sensory overload (little wonder Burroughs was called the godfather of cyberpunk), the book pushes every rhetorical device to its limits to depict the living hell of a drug addict and the corruption of society and its views of morality.

There was a strong reaction to such a picture of reality stripped bare: the book was declared obscene in Boston in 1962, giving it outlaw credibility. Four years later, the ruling was overturned by the Massachusetts Supreme Court in 1966. Now the book had social value as well.

As a recovering addict, Burroughs saw drugs as part of a control society. The drug controlled the addict. Those in charge controlled both. The film I will re-view put Burroughs’s jeremiad up against the “just say no” inanity of 1980s drug hysteria.

“We Played a Game You Couldn’t Win”: Drugstore Cowboy

(dir. Van Sant 1989)

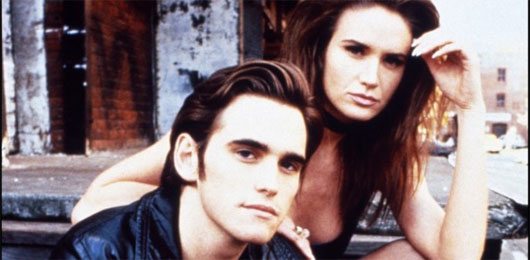

The narrative about the life of an addict, Bob, who steals drugs and then cleans up, is, after all, rather standard, with Bob’s voice over telling us the story. Matt Dillon, who plays Bob, tries his best to add grace notes to suggest his damaged soul, but, overall, the story is predictable.

What makes Drugstore Cowboy significant is how it creates a visual tone poem about the cycles of addiction, featuring images cut and pasted together like in Burroughs’s book (we are reminded that Burroughs said the chapters could be read in any order). It is an ugly beauty—as what goes on in Bob’s head surely must be. As he nods out in the back of a car, his blood fills with drugs, and so does his stream of consciousness: a surreal series of objects, a house, a tree, animals, float by him. But the high never lasts long, for these transcendent moments are then crashed by waves of fear, repulsion, and disgust.

The early-70s setting emphasizes a dirty feel; the raw, fuzzed-out guitar riff of The Count Five’s “Psychotic Reaction” soundtracks the adrenalin rush of the heist and after party. As gang leader, Dillon exudes an authority in the film he seems to be able to modulate at will, but is not afraid to make his character appear slightly ridiculous. Although Bob’s superstitions (such as not putting a hat on a bed) have a sort of overworked logic to them, they speak volumes about his fatalism about life: “We played a game you couldn’t win.”

James Le Gros plays Rick, the gang’s muscle, whose view of life is so literal that he tends to use Bob’s name in every exchange with him. With a fully amped-up attitude, he makes it hard to tell whether his clumsy attempts to draw attention away from Bob are tragic or comic. At first, we get the feeling he will have a short life and won’t even appreciate it because he is so resentful. Then we start to believe he might be smarter than he looks.

Bob’s gang is pursued by a cop who could have stepped out of Dirty Harry. But the film puts us on Bob’s side: through his perspective we question whatever sense of morality the cop uses to explain the laws he enforces. And enforcing those laws ends up creating better, more clever criminals. As Bob says, “Man, I love cops. If there were no hot shit cops . . . the competition would be so heavy there’d be nothing left to steal.”

The hallucinatory environment we are plunged into makes even the familiar rules of outlaw life seem as if we are viewing them from a somewhat different angle. The first rule is there is no honor among thieves. Paranoia, rip-offs, backstabbing abound, of course. Yet the dosage of drugs can be hard to calculate, especially when already altered. Although we can see and feel the graphic effects of the highs and lows, there is a sense of something we can’t see and can’t feel. We wonder when bodies and minds will give out: where the breaking point is, the tolerance exceeded.

The second is relationships are hard, if not impossible, to maintain. Kelly Lynch, who plays Diane, Bob’s wife, does an amazing job of showing how drugs can create feelings of isolation and disconnection. What Lynch seems to realize is that drug trips can’t really be shared—or are felt in the same way by everyone—and so she plays her character with a visible sex drive that further distances Diane from Bob, whose taking of opiates diminishes his sexual desire. In an example of the film’s open-mine-shaft level of humor, again influenced by Burroughs, she complains to Bob about her life and role in the gang: “You won’t fuck me and I always have to drive.”

The film hints that Bob and Diane’s love cannot be conventionally expressed: the overtones of queerness resonate from the lived experiences of Burroughs, who later appears in the film, and Gus Van Sant, both openly gay. Burroughs wrote an early short novel, Queer. Two years after Drugstore Cowboy, Van Sant wrote and directed My Own Private Idaho (1991), which foregrounds the issue of homosexuality. Returning to Drugstore Cowboy, drugs block the honesty needed for Bob and Diane’s relationship to ever stabilize.

The third rule, of course, is no good deed goes unpunished. The ending, while about a drug-motivated revenge, conveys a larger point that Bob cannot escape his fate even by getting clean. As Bob earlier puts it, “We played a game you couldn’t win.” The startling realism of Drugstore Cowboy about the pleasures of drug-taking carries with it a metaphysical dread that goes beyond the needle: it is the naked lunch that control society rarely, if ever, lets us see.

Bob’s decision to go clean is, in some ways, triggered by the accidental fatal overdose of Rick’s girlfriend in the gang (which occurs out of Bob’s, and our, view). He feels responsible, suggesting how he displaces concerns about his own life and Diane’s, but is even more anxious about how the state law regards overdose as murder, which could mean doing serious time.

By going clean, he loses Diane for good, who is fully immersed in the drug life. What is a cliché in this sort of story is rescued by Lynch’s performance that plays off of gender stereotypes: Diane’s sneering refusal to enter recovery tops off the corrosive anger she has been radiating for most of the film and shows how drugs fuel the fantasy of being/acting tough. In a further power reversal, she tells Bob she is now a member in Rick’s gang—and possibly his girlfriend.

At the end, Bob’s new life finds him meeting the unrepentant Tom the Priest. Their scenes together are some of the most memorable in the film. They drive home the point about society’s needing outlaws and how attitudes about the morality of drugs enable addicts to conveniently fit this role.

Played by Burroughs, Tom looks as if he stepped out of an author’s portrait, dressed with quiet dignity in a suit and hat. Burroughs’s eyes suggest that he has seen much that we would never want to see. He gives Tom, who remains an addict, a gravedigger’s cadence as his brief morality lesson registers irony from no matter what time period, in the 70s, 80s, or right now: “I predict in the near future right-wingers will use drug hysteria as a pretext to set up an international police apparatus.”