Reagan’s Morning in America was a dream world, suggesting that even the more massive historical blunders of the nation, such as the recent trauma of Vietnam, could be corrected. Taking the disillusionment of Vietnam veterans that Bruce Springsteen sang so powerfully about in “Born in the U.S.A.” (1980) and turning it upside down, Rambo: First Blood Part II (1985) acted out the right-wing fantasy of re-fighting the war, and this time “being allowed to win” (this meme still in active circulation suggests that the troops were overly constrained—although I think that the My Lai atrocity questions such a myth). Reagan even tried to appropriate “Born in the U.S.A.,” but Springsteen refused to let him do so; Springsteen felt about Reagan the same way he now feels about Chris Christie.

The amnesia about history that Reagan encouraged blocked out some of the darker aspects of Vietnam. As a prime example, Nixon’s “secret bombing” of Cambodia led to the Khmer Rouge uprising and one of the larger genocides in history. The Killing Fields (1984) took a rather unflinching look at what happened. The film I will now re-view is about the experiences of an actor, who had a small role, during the filming.

In Search of the Perfect Moment: Swimming to Cambodia

(dir Demme 1987)

To address the artistic breakthrough of this film requires going back to 1978. The Last Waltz, released in this year, signaled the twilight of classic rock. Documenting the farewell performance of The Band, the group that backed Bob Dylan but a fine musical collective in its own right, the film chronicled a grandiose (the show was on Thanksgiving in 1976), fascinating, and, by all accounts, messy event. Dylan plays with The Band at the concert, as do many of the musicians of the classic rock era. The lasting image of the film: Robbie Robertson from The Band, coked-up and exhausted from the marathon show, bending notes on his guitar, radiating a coolness under pressure.

Robertson’s friend and confidante, Martin Scorsese (the drug-fueled antics of the two together are the stuff of legend) directed The Last Waltz. But the stage volume was so loud that Scorsese could not relay any directions to the camera crew, forcing him to throw out the carefully-planned storyboards he had devised for each song and improvise.

In the early 80s, the post-punk art scene had a somewhat different kind of cool: a chilled-out minimalism that tended to avoid improvisation. The Talking Heads embodied this ethos—throughout their career their skeletal funk music was carefully arranged; even David Byrne’s casual observations of daily life featured in the songs seemed thoroughly worked out. Stop Making Sense (1984), the band’s concert film, directed by Jonathan Demme, used the stage as a performance space, filling it up gradually, until the finale where the band with an array of backing musicians plays spacey, looping grooves.

Two years later, performance artist Laurie Anderson filmed her live show Home of the Brave (1986). Directed by Anderson, the film has promise (due to the striking visual imagery in her work) , but, at times, she appears stranded on stage during the musical parts of the show as she is forced to assume the role of a lead singer and hold our attention—unlike Byrne, she cannot put on a guitar and fade into the background. Home of the Brave seems stuck between the immediacy of a rock concert and the detachment of a conceptual art exhibit (few have pulled off this combination, and the list of those who have is endlessly debatable).

The stage was thus set for someone like Spalding Gray to come along and take everything from the early to mid 80s and make it his own. A member of the New York experimental theater scene (he co-founded the Wooster Group), he was part of the same artistic circle as the Talking Heads and Anderson. He devised monologues that worked through his hang-ups about sex and death that stemmed from his childhood (having been brought up in a Christian Scientist household). Rather than use Bergman as a guide, like Woody Allen did, Gray used Eastern philosophy and, at times, New-Age mysticism.

What Gray could do exceptionally well was combine the real and the imaginary, like he did as an actor playing roles such as Hoss in Sam Shepard’s play The Tooth of Crime. In a letter, he recounts the feeling of dropping character at the end of the play (upon the director’s request) and standing on the stage in front of the audience. Such an experience helped Gray hone the razor-edged theatricality of his works.

Swimming to Cambodia is shaped by a challenge: for Gray to find the perfect moment in a place well-suited for it. Several times Cambodia is described as a paradise—which Gray juxtaposes with the recent history of genocide. What is this perfect moment? The answer Gray gives is that he will know it when it happens. All the stories in the film (cut down from a longer version he performed repeatedly in New York City) are arranged to lead up to his discovery.

Demme, who earlier filmed the Talking Heads, captures Gray’s offbeat riffs with a precision that would show up in the early-90s award-winning films, The Silence of the Lambs (1991) and Philadelphia (1993), that he directed. In Swimming to Cambodia, Demme creates a spectacular fusion between storyteller and story, an even more impressive feat considering the film was shot in two days. Like in Stop Making Sense, the stage is a performance space, minimally adorned.

Gray holds our focus for the entire film by refusing to isolate or downplay the tensions that his search for the perfect moment produces. Is he delusional, or worse, for making the filming of The Killing Fields (in which he has only a small part) all about him? Does his self-conscious role as witness to history come across as voyeuristic? How does all his talk about temptation (especially of the sexual kind) register to his girlfriend–Grey frequently brings up their relationship—waiting for him in New York?

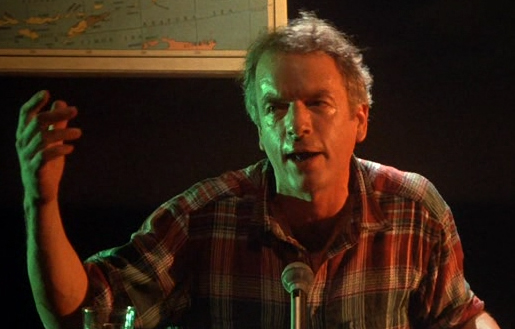

The stories are hypnotic, told by Gray, who is seated at a desk, reading from a notebook. Thudding music by Anderson, lighting changes, and camera shifts occasionally register to us—that they stay out of the way, for the most part, makes for an artistic economy that melds with the intensity that Gray projects. No matter how absurd, even twisted, Gray gets, his vocal steadiness and appearance, dressed in a red and green plaid shirt with the sleeves rolled up, make him believable (he says early in the performance that all the events, except one, that he describes are real). We are watching one of the oldest dramatic devices in the book, a person telling stories about himself, get retrofitted for the artistic philosophies and socio-political conflicts of the 80s.

The film’s less-is-more aesthetic seems of the moment as Gray presents us with an inventory of what is on his mind at the time, further animated by the experiences of travel in an unfamiliar country. Swimming to Cambodia ends, after Gray has had his perfect moment (which, we are reminded, may not, and does not have to, be perfect to us) with his reflecting on the death of Marilyn Monroe. What would seem like a strange idea to include, much less end with, makes almost perfect sense: with the skill of a virtuoso, Gray has mixed up our ideas about pleasure and death until they have the danger and allure of being real–and, at the same time, imaginary–things.