In his bestselling book, Easy Riders, Raging Bulls: How the Sex-Drugs-and-Rock ‘N’ Roll Generation Saved Hollywood (1998), Peter Biskind voices the well-rehearsed argument that after the 1970s–the “golden decade”–there was a pronounced drop-off in the artistic quality of U.S. films. As Julius Kassendorf, founder of The Solute points out (in an email conversation), this argument is based on two premises. First, the 1980s did not feature films made by directors regarded as auteurs, that is, as having the final word in decisions about the filmmaking process. The 1970s had any number of directors who could be seen in this way, for example, Coppola, Scorsese, Spielberg, etc. Second, the major studios, in the 1980s, no longer helmed adventurous works, geared as they were to turning out blockbusters that relied on tried-and-true approaches.

In this multiple-part series, I will discuss films that demonstrate that, even if the above premises hold, artistic quality, in the 1980s, had not, overall, declined. For films in this decade opened up new ways of seeing, thinking, and feeling. It is this idea I want to explore—on a film-by-film basis.

“This Story Is All We Have”

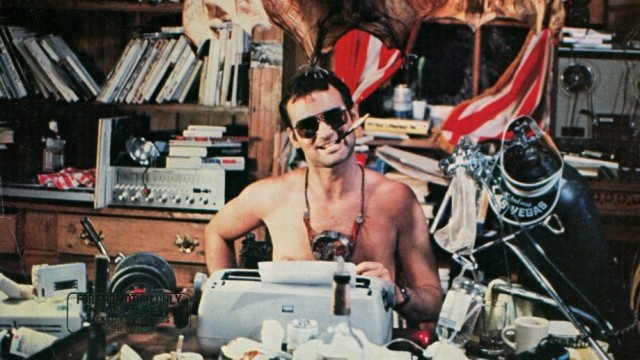

Where the Buffalo Roam (dir. Linson 1980)

One major way the late 1970s would influence 1980s film is the career trajectories of Saturday Night Live alumni. The late-night television comedy series elevated comedians, as asserted in the book, Live From New York: An Uncensored History of Saturday Night Live (2001), to the popularity and celebrity of rock stars. One of the earliest stars, Steve Martin, who hosted many of the standout shows, was a comedy innovator whose deconstruction of standard gags in his routines fit well with the edgy style of SNL—in particular, the tendency to revel in drug-laden and political humor that constantly flirted with censorship (just as music and film did around a decade earlier). In addition, the performers, especially John Belushi, tended to act as if there were little distance between life on- and off-set.

Belushi hit the big time with Animal House (1978); while his acting career in film was undeniably solid, it was cut short by his untimely death (due to a drug overdose). But it is Bill Murray who, arguably, has had the most outstanding career of all the SNL alums. What I think is an important piece of supporting evidence is Where the Buffalo Roam, a film based on the late-1960s and early-1970s adventures of the politically-progressive and nonconformist writer Hunter S. Thompson, who invented “gonzo” journalism, where no pretense is made about maintaining an objectivity about what is being observed (this also gives license to exaggerate certain elements of a story for thematic or creative purposes).

Murray had made a sizable impact in films following the slobs vs. snobs template of Animal House: Meatballs (1979) and, in the same year as WTBR, Caddyshack (1980). But this film presents Murray with several major challenges. The primary obstacle was the first-time director, Art Linson, who would go on to direct only one more film, The Wild Life (1984). Whether WTBR is watched once or repeatedly, it will be clear that Linson adds very little to the film; he certainly does not fit the 1970s definition of an auteur. The second challenge is capturing the persona of HST, whose artistry and politics went beyond simple shock value, even if his writing rarely passed up the opportunity to engage in self-mythologizing. Read any of his three books, Hell’s Angels (1966), Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (1971), and Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail ’72 (1973), and it should be evident that he should be taken seriously as a post-WWII literary author. In 1970, he even ran for sheriff in Aspen, Colorado on his own “freak” ticket, and came close to winning. The third problem is the distracting presence of Lazlo, played by the formidable, in both stature and acting ability, Peter Boyle. In keeping with the over-the-top tone of the film, Boyle takes to heart the anarchic energy of Lazlo, whom the film depicts as overall even more unhinged than Thompson. Why I say his presence is distracting is because HST’s real-life sidekick was the Chicano activist and lawyer Oscar Zeta Acosta; taking artistic license to the surreal heights HST was known for, he portrayed him as a Samoan. The film unfortunately follows the Hollywood tradition of casting white actors in non-white roles. And, need it be said, nothing that Boyle does makes us forget this.

So Murray has to do heavy lifting for the duration of the film. And he pulls it off, getting inside the character with voice inflections, sudden mood shifts, and a demeanor that suggests–more dazed than confused–that he is tuned into his own private cosmic signal. While Murray hung out with HST, it is rather unlikely anyone would mistake the two, unlike Johnny Depp’s portrayal of HST in Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (1998), which is a performance that comes close to ventriloquism, or channeling.

It is hard, I would argue, not to read into HST’s openly-stated preference for Depp over Murray, for Murray gets at a vulnerability of HST, his self-consciousness about his own persona. While I am speculating here, it seems that it bothered HST that Murray, no matter how deeply sunk into the role, was still acting, still making choices (some HST obviously disagreed with), which meant, of course, that Murray could, at some point, exit the character. In contrast, as the 1978 BBC documentary on HST (included with the Criterion DVD of Fear and Loathing) highlights, HST was feeling, at the time of the making of WTBR, especially trapped in his persona. In the documentary, HST even mentions the possibility of killing “him” off. (But, during his life, HST never found a way out: growing older and weaker, he committed suicide in 2005.)

Murray’s using HST’s self-consciousness as part of the role creates a critical distance from even the most cartoon-like scenes in the film and draws attention to the one serious theme that emerges: the role of the journalist and writer in activist movements. While The Big Chill (1983) would a few years later cover, in a more self-absorbed way, the debate about “selling out,” none of the fictional characters in this film, I think, had as much to lose as the real-life HST. As I will suggest, the ending of WTBR has a sadness that suggests, on multiple levels, that he was a front-lines observer to the final dimming of the late-sixties energies that had propelled his career.

From the start of the film, the focus is on documenting such history. Two hours until deadline, HST is at his home trying to write an article for a magazine, Blast, that is the fictionalized counterpart of Rolling Stone, which had regularly employed HST (and helped to boost his underground popularity). The film thus purports to cover almost in real time (the film runs 100 minutes) the writing process. Murray’s voice, as he struggles with writer’s block (making him sympathetic to nearly all writers), conveys with deadpan humor a lack of concern at the deadline. He projects an air of cockiness and a sense of skewed professionalism about the task at hand. But Murray’s body language paints a different picture; he is agitated as if he has been plugged into a powerful electrical current. Granted, the heroic levels of consumption of drugs and alcohol that never lets up during the course of the movie is a major contributor to his edge-of-sanity behavior. HST boasted, in and out of print, about his drinking, drug-taking, overall recklessness, and other illegal, subversive, and reality-bending acts. For him, like many other artists, he felt the derangement of the senses was crucial to his creative drive. This philosophy is summed up in a later scene in the film, reminiscent of HST’s college lectures, where he tells the audience, “I hate to advocate weird chemicals, alcohol, violence or insanity to anyone, but they’ve always worked for me.”

By 1980, however, it seemed an open question whether such a self-proclaimed outlaw lifestyle was still working for HST. His editor at Rolling Stone, Jann Wenner makes it clear, in Gonzo: The Life of Hunter S. Thompson (2008), that he felt the overall debauchery was negatively affecting HST’s productivity. Published in 1979, a collection of articles by HST, The Great Shark Hunt (the last work that, I would say, could be considered as significant) hinted at a decline. While some of the pieces are brilliant, others seem rote—as a whole, the volume does not fully compensate for the fact that HST, at the time of the film’s release, had not published a book-length work for over five years (and never would do so for the rest of his life).

Now the film is decidedly not moralistic, treating HST’s antics primarily as fodder for comic scenes (which we will get to shortly) and even suggests other reasons for his writer’s block. The beeping of the teletype machine, on his desk, symbolizes the artistic interference that HST constantly faced, even from sympathetic employers like Wenner. HST’s success as a journalist was a double-edged sword; while article writing was lucrative, it took time and energy away from more literary pursuits. The demands of being a “professional,” requiring him to face a gauntlet of deadlines, length/content restrictions, and other distractions, constantly irritated HST and further provoked his outlandish behavior.

It is significant, then, that, in the film, what starts HST writing is his memories of Lazlo. Murray’s laconic voiceover, as the scene shifts to San Francisco, 1968, conveys the turbulence of the times (as the rise of Nixon signaled political repression against protest and dissent) and, at the same time, his derogatory attitude about his job:

This won’t be the first time I got sucked into writing about Lazlo. . . . This was the man I counted on to keep me out of jail in those years, those weird years between the ‘60s and the ‘70s, the age of Nixon. It was a time to keep your head down. I was a working journalist, a hired geek of sorts, and Lazlo was great company and sometimes a good lawyer. It was a fast strange time, and we worked in fast, strange ways.

Lazlo acts as HST’s political and artistic conscience, while HST documents Lazlo’s attempts to combat a legal system rigged against the powerless—especially against the young.

In a brilliant and funny scene, HST is typing while driving, Lazlo, in the passenger seat, dictates to him his thoughts about the importance of the Fourth Amendment. As the car descends a steep hill, another car is cut off. At the bottom of the hill, a policeman is frisking several young hippies who have their backs against a wall. The other car crashes into the policeman’s motorcycle. Distracted, the policeman turns around and screams at the driver, which allows the hippies to escape. IMO, this scene is funnier than the entire protracted car chase of The Blues Brothers, released in 1980 (the same year as WTBR), starring Belushi and Dan Aykroyd, that was based on their popular SNL skit—and, for me, a prime example of turning a promising idea (working musicians, with compelling back stories, trying to get by) into a cartoon.

The similarities with The Blues Brothers do not end here. Like that film, WTBR features comic set pieces around an action/adventure plot. In The Blues Brothers, the musicians are on the run from the police, while, in WTBR, HST gets involved with Lazlo’s aiding political revolutionaries. Here it is worth noting that the drugged-out haze of HST is used to excuse the plot contrivance of how he keeps running into Lazlo. Moreover, much of the film’s humor relies on creative translations of HST’s articles. For instance, in reference to HST’s covering the 1972 Super Bowl, Murray recruits a maid and bellhop to participate in a football game in his luxury hotel suite, resulting in widespread destruction. Other attempts at translation do not work as well. A bathroom encounter with Nixon (HST’s openly-proclaimed, real-life nemesis) comes off as wooden and staged, while Murray’s off-key singing of The Beatles’ “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” in the press-plane cockpit appears derived from Murray’s lounge-singer SNL skits.

If the press-plan e scene comes off, to me, as overwrought, it does set up HST’s final encounter with Lazlo. Lazlo appears on the runway and tries to recruit HST into participating in his latest wild scheme: building his own private kingdom in the middle of nowhere. The resulting exchange hits the right comic notes, as both HST and Lazlo act as belligerently and stubbornly as can be imagined. Here the clean-cut HST, who has been impersonating a reporter for an establishment newspaper, represents pragmatism, while Lazlo, even more manic, exhibits an idealism that has morphed into full-blown radicalism:

e scene comes off, to me, as overwrought, it does set up HST’s final encounter with Lazlo. Lazlo appears on the runway and tries to recruit HST into participating in his latest wild scheme: building his own private kingdom in the middle of nowhere. The resulting exchange hits the right comic notes, as both HST and Lazlo act as belligerently and stubbornly as can be imagined. Here the clean-cut HST, who has been impersonating a reporter for an establishment newspaper, represents pragmatism, while Lazlo, even more manic, exhibits an idealism that has morphed into full-blown radicalism:

HST: You already live in the land of the weird. What do you need?

L: Fuck, man, you’re a writer! Use your imagination! . . . We’ll build a goddamn

paradise! . . . We got land! We got dope! We got women!

HST: What kind of women would go there? You’ve got shitty dope.

During the argument, Lazlo’s briefcase opens, and papers fly out. HST helps Lazlo collect the papers that have scattered all over the runway, blown by the wind. We hear the sound of a typewriter. The scene shifts to HST, at home, typing the article. As he finishes it, with bravado, he pulls the page out of the typewriter and reads aloud:

Well, I guess if I had to swear one way or another, I’d say Lazlo wasn’t insane. He just had very strange rhythms. But he stomped on the terra. Lord Buckley said that. It’s hard to say . . . he got what he deserved, because he never really got anything. At least not in this story. And right now, this story is all we have.

In the midst of the adrenalin rush (further intensified by exhaustion, alcohol, and drugs) of having finished the article with little time to spare, Murray injects grace notes in his reading that suggest profound regret. Prompted by Lazlo’s remark, “[Y]ou’re a writer!” (as opposed to being a paid journalist), which carries with it an accusation of escapism, betrayal, and denial, he deals with his conflicted feelings about his friend. That he says, in the article, that Lazlo “wasn’t insane” implies that Lazlo’s going further underground in response to increasing repression in the country was done out of a genuine sense of political consciousness and commitment—which Murray, as HST, knows he simply cannot have if he wants to live life his way. And this lack is what HST’s real-life work, at its finest, frequently addressed. HST was too politically educated to be able to overlook the limits of activism as they appeared more visible when late-1960s optimism faded: too often, he says, those committed to the cause “never really [get] anything.” They are, at the least, disappointed. At the worst, they meet cruel ends. (Such, indeed, was the case of Acosta, who disappeared in 1974.)

In the film, Murray captures, in all its light and heat, HST’s conviction that it is not wrong to endorse activism if one cannot be an activist, but the price, even (and especially) if the feeling is expressed in good faith, is always remembering the difference between thought and action. Such are the haunting words: “This story is all we have.”