“It is Tarantino’s strategy in all his films to have the characters speak at right angles to the action, or depart on flights of fantasy…Watching many movies, I realize that all of the dialogue is entirely devoted to explaining or furthering the plot, and no joy is taken in the style of language and idiom for its own sake. There is not a single line in Pearl Harbor you would quote with anything but derision. Most conversations in most movies are deadly boring, which is why directors with no gift for dialogue depend so heavily on action and special effects. The characters in Pulp Fiction are always talking and always interesting, funny, scary, or audacious. This movie would work as an audiobook. Imagine having to listen to The Mummy Returns.”

– Roger Ebert

“Why do we feel it’s necessary to yak about bullshit in order to be comfortable?”

– Mia Wallace

English, Motherfucker, Do You Speak It?

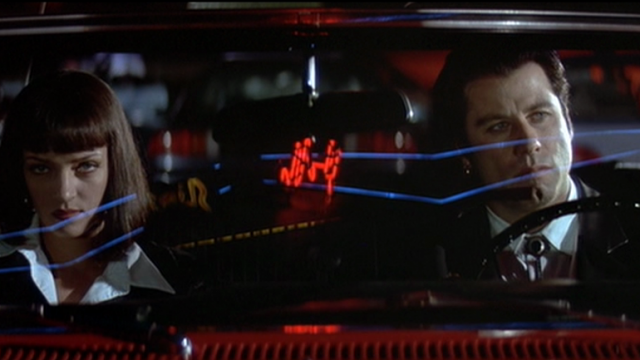

That yakking is the first thing you have to talk about when you talk about Pulp Fiction. At its heart, it’s just another crime thriller, or anyway, several stitched together. But these people don’t talk like characters in a thriller. Like Ebert says, they talk at right angles to the plot. What they say isn’t specifically relevant to it. But it is relevant to who they are, and more than that, to the “joy taken in the style of language for its own sake.” Maybe there was something in the air when it came out: Seinfeld made its name as “the show about nothing,” becoming the biggest thing on TV by showing its characters nattering about the same minutiae that fascinate Jules and Vince. The very same year, Kevin Smith would prove movie audiences would watch these kind of rambling conversations without even needing a plot to hang it on in Clerks. The dialogue here isn’t the kind workmanlike prose of Pulp Fiction’s namesake. It’s profane poetry, made all the more so by the musicality of voices like Samuel L. Jackson’s, Ving Rhames’, and Maria De Medeiros’, or the improvisational jazz rhythms of Harvey Keitel and Christopher Walken. No wonder Jackson, as the hitman Jules, seems more offended by his victim’s incoherence than anything else. To see how brilliant it is, all you have to do is compare the Pulp Fiction soundtrack to the ones from any of Tarantino’s other films. They all intersperse Tarantino’s library of golden oldies with snippets of dialogue, and the difference is striking. The most utilitarian, throwaway lines in Pulp Fiction are as memorable and tightly written as any of his other movies’ iconic signatures, let alone anyone else’s. Sure, Inglourious Basterds is cool, but is it the namesake for an electronic duo?

Could this be because of his screenwriting collaborator Roger Avary? Given that Avary’s future career included such credits as Silent Hill and Beowulf, probably not. Maybe they had some magic together they couldn’t capture apart, Wonder Twins-style. Maybe Tarantino bought his own hype and it led him to overstretch his scripts into three-hour monsters where he was able to tell three or more stories in that time here. Or maybe it was just lightning in a bottle. Even for fans of his later work, it’s hard to deny there’s something special here, a shock of the new that’s hard to sustain over a two-decade-plus career. If it were any easier to recreate Pulp Fiction, even by its creator, surely there’d be more movies this good. As it is, we’re lucky to at least have the one.

The First Watch

That shock of the new was definitely there when I first saw it nearly a decade ago. Like many of us, I came to it as a baby cinephile. I was starting to replace my aimless movie selection at the local video store (R.I.P.) with what I called “bucket listing.” Combine that with Netflix’s stunning turn-of-the-decade catalog (R.I.P.) and I had the best film school a teenager could ask for. I was seventeen or eighteen, and since I was a bit of an autonarc, just acclimating myself to the R-rated side of movieland. So I was prepared to be shocked by Pulp Fiction, and I was, but not in the way I expected. What got me was the audacity of Tarantino’s style: when Uma Thurman said “don’t be a…” and a square actually appears as her fingers trace in the air, I was so blown away I couldn’t help laughing. (It’s actually a rectangle, but who’s counting?) I think that’s what make Tarantino so appealing to young people discovering film, and why he’s been able to transcend the “film bro canon”: you come for the sex and violence, but you stay for the cinematic craftsmanship. I called Netflix’s old catalog a film school, but Pulp Fiction can be one all by itself. Tarantino pulls out every tool in the kit and shows the best uses for each of them, with all the energy of a young director who wants to get everything into his move because he might never get to make another one.

An According-to-Hoyle Miracle

But what struck me more than anything about Pulp Fiction was something I never expected to find in this amoral world of killers and thieves, and that is a strong, even unyielding moral and spiritual core. We see it develop across the three stories: as Vincent, John Travolta does something heroic (saving Mia’s life) not because of his own goodness, but because he’s terrified of the consequences if he doesn’t. As Butch, Bruce Willis faces consequences if he does do the right thing, facing the wrath of two violent maniacs to save the life of a man who wants him dead. And then there’s Jules. He escapes the consequences of his actions when some anonymous loser empties a full clip at him and misses every single time. And somehow, in this very carnal world of drugs and violence, he has a spiritual awakening. This leads Pulp Fiction to pull out one of my favorite but also most frustrating tricks in fiction: suggesting a story that sounds even better than the one we’re watching, but that we’ll never get to see. Jules says he’ll spend his remaining years atoning for his life of crime and “Walk the earth, meet people… get into adventures. Like Cain.” Except he’s not talking about the biblical wanderer, but the star of Kung Fu. Carnal meets spiritual, trash meets theology. The next thing Jules does is pass on the mercy he believes God has shown him. He proves to the stick-up artists Pumpkin and Honey Bunny that he could kill them, but that he’s going to let them continue to live, so that they can live better. Pulp Fiction seems to be, with Kendrick Lamar’s Good Kid, mAAd City, one of the last secular (i.e., good) narratives to take being “born again” seriously.

The Marvin Situation

At least, as seriously as it takes anything else. Pulp Fiction is a deeply unlikely conversion story, and not just because of the sex and violence – by that standard, most of the Bible wouldn’t fit either. That aspect of the movie’s world actually deepens its impact: where most Christian works make heaven seem impossible by skimming over everything that makes the earth what it is, Pulp Fiction makes the spiritual believable by grounding it in the ugliness we know. What’s harder to swallow is that something so cornily sincere could exist in a work of such arch nineties irony. The grit and violence of Pulp Fiction’s universe may be earthy, but it’s not the same earth we live in. In fact, there’s something more frightening than all the bloodletting in the film: the idea that this world is trapped in a seventies that never ends! Despite some convenient (if nineties-sized) cell phones, the present-day timeline is the disco era from top to toe, from John Travolta’s saddle shoes to Samuel L.’s mutton chops. And yet somehow, Butch’s father died in the Vietnam War. Jackrabbit Slim’s just confuses things further. It’s an expensive reservation-only establishment (five dollars for a milkshake doesn’t seem as astronomical now, but hey, those are nineties and/or seventies dollars!) that painstakingly recreates a cheap, tacky diner from another era. (Given Tarantino’s obsession with Travolta’s fading career, you have to wonder if he was inspired by The Simpsons’ dig at it: the same year, the family goes to a seventies-themed restaurant where, just like Slim’s, all the waiters are dressed like celebrities from the era. Marge points out a waiter who looks just like John Travolta, and he mutters, “Yeah…looks like.”) And time isn’t just mixed up in terms of years: it goes down to the hour too. There’s the chopped-up chronology, of course. But let’s not forget the third chapter and the beginning of the first take place early in the morning, because it’s easy to. Brett’s eating lunch for breakfast; the Wolf is inexplicably in evening dress at a high-class dinner party.

At first, opening with a title card quoting from the dictionary seems embarrassingly amateur-hour, but it also introduces a helpful double meaning: as well as describing the lurid excess of Pulp Fiction’s world, pulp can also mean “A soft, moist, shapeless mass of matter.” This isn’t a biblically ordered universe: it’s a shapeless mass of times and places filtered secondhand through disposable pop culture with no pretensions to reality. Just look at Butch’s cab ride: the backdrop isn’t just a cheesy old-timey rear projection, it’s a cheesy old-timey rear projection in black and white. Airplane! had more commitment to realism in its driving scenes. Even Jules’ iconic Bible passage isn’t real. There’s a little bit of the given reference (Ezekiel 25:17) mixed up with bits of the 23rd Psalm, the Sermon on the Mount, and the story of Cain (but not from Kung Fu). This is Tarantino treating the scriptures like he treats film history: the Bible in a blender. Or at least, that’d be a nice narrative: it’s actually taken word-for-word from a specific source, the Sonny Chiba martial-arts movie The Bodyguard.

If nothing is real, does anything matter? If the verse that inspires Jules’ conversion is a parody, is the conversion itself a joke?

But that’s still not certain. To quote Pulp Fiction’s Oscar rival Forrest Gump, “I don’t know if we each have a destiny, or if we’re all just floating around accidental-like on a breeze.” The six shots that miss Jules each seem predestined. That’s certainly what he believes. But what can we make of it when, in the middle of discussing this divine plan, a random shot blows the head right off of an innocent man “accidental-like?” In this world, life is so cheap that Jules can kill a man mid-conversation and mock his friend for being rattled by it.

Does He Look Like a Bitch?

But, fittingly for such a tightly-plotted and -written film, there’s the frame of a rigid moral order in its structure. We already know when Vincent rejects Jules’ offer of salvation that he’ll pay for it, dying ignominiously on the toilet, shot by his own gun, still reading the same book he brought into the bathroom at the coffee shop. It’s good for a chuckle when Butch looks around the pawnshop like a kid in a toy store to find the right implements of death to take downstairs, but it’s more than that. He goes to protect his master with a samurai’s katana blade, embodying the rigid moral code of bushido. After all, he’s been living that code throughout his story. He betrays the code of the mob by taking a bribe to throw a fight and then winning anyway, but this is how he stays true to the higher moral code of the ring. He risks his life in order to save his forefathers’ inheritance (even if Christopher Walken’s ass-heavy monologue reminds us how ridiculous these ideals are). He brushes off Esmeralda the cabdriver when she asks what his name means: “I’m American, honey. Our names don’t mean shit.” The truth, of course, is it means “manly.” Even if it’s midcentury slang instead of the language of the “old country,” Butch is still rewarded for living up to the ideals of traditional manhood. (And yes, that does make his domestic violence and the evil gay kinksters even more uncomfortable, why do you ask?)

Marcellus Wallace serves as the unconventional moral center of Pulp Fiction’s universe. He’s not romanticized in the style of Don Vito: he’s pretty clearly a bad dude who gains his power from having other bad dudes kill worse dudes (or, anyway, dudes who are worse at being bad dudes). Might makes right. All the same, we see Butch being cosmically punished for double-crossing him and rewarded for saving him. And even post-miracle, Jules refuses to start on his new life until he can return Marsellus’ briefcase. There’s your bushido: the question isn’t whether he deserves loyalty. The pledge is all.

And then there’s Jules. The language he uses when he negotiates with Pumpkin and Honey Bunny is the same used to describe the biblical New Covenant: “Wanna know what I’m buyin’, Ringo? Your life. I’m givin’ you that money so I don’t have to kill your ass.” In other words, he’s literally redeeming them. If Jules, and by extension Pumpkin and Honey Bunny, are really on the path to salvation, they’re going somewhere Tarantino can’t follow. The universe of hate and violence is the one he created; maybe the characters can only find redemption by leaving it entirely. Maybe that’s why it ends so abruptly. In order to walk the earth, Jules exits the film; not quite walking into the sunset, but walking out of the film.