Alfred Hitchcock was already a respected and successful director by the time he made Psycho in 1960. The master of suspense and psychological thrillers had made some hit films, but Psycho was a smash. Made for $806,947, it grossed over $32 million.

Hitchcock meticulously and purposely shot Psycho in black and white not only to keep the budget down, but also to de-emphasize the gore of the famous shower scene. Instead, he relied on the other technique he was a master of: manipulation. As Hitchcock told fellow director François Truffaut, “It was rather exciting to use the camera to deceive the audience.”1 Every shot and every angle went toward that deception.

To backtrack a bit: Nowadays, it’s more common for a well-known actor to be killed in the beginning of the film; see Drew Barrymore in the opening of 1996’s Scream. But in 1960, audiences going to see a Janet Leigh film expected to see Janet Leigh throughout the entire film. And when the film starts as more of a crime thriller, where Leigh’s Marion Crane steals $40,000 to start a new life with her lover, you couldn’t blame the audience for expecting to see her either get caught or get away.

Except she doesn’t do either because she has the misfortune to stop for a night at the Bates Motel.

Approximately 47 minutes into the film’s 109-minute run time, Marion is murdered. The actual attack lasts less than a minute, but the shock and terror – especially for an audience unprepared for their crime film to suddenly become a horror movie – lasts long past the final credits.

So what gives Psycho its enduring power to scare, even as what powered its main shocks in 1960 is more run-of-the-mill today? I would argue it all comes down to the shower scene, a scene that for all its blood and Bernard Herrmann’s piercing, screeching violins, eschews explicit gore for psychological resonance. Never once does the blade pierce Marion’s body, or even get that close to her, but through a series of quick cuts, Hitchcock makes you think you saw a graphic death. I know people who to this day swear they saw Marion get stabbed in the stomach. But it simply doesn’t happen.

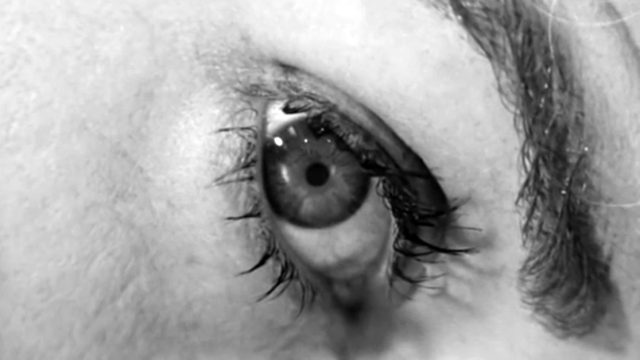

The other reason is how ordinary the scene is. A woman gets into a shower, starts soaping up, and seems at peace (Marion had just decided to go back home and confess she stole the money). The music stops, giving way to the natural sounds of the shower. Everything is normal. Then a shadow appears behind the shower curtain, getting closer until the intruder pulls back the curtain and raises the knife. The terror on Marion’s face, coupled with the horrible sounds of a blade slicing into flesh, and ending with the dying Marion slowly reaching out and pulling the shower curtain off the rod before slumping over the tub onto the bathroom tile, is unnerving. I’ve got goosebumps just typing this out. As Hitchcock dissolves between the blood going down the shower drain and Marion’s open eye, the drops of water look like tears. After the attack ends, the score again gives way to the diegetic sound of the shower. It’s absolutely unsettling that something so private is so grossly violated.

I asked my mom, who had seen Psycho when it came out, if audiences really were that surprised, and she told me it was completely shocking and made her afraid to shower for a long time after (like mother, like daughter in that respect!). My high school film teacher told us the same thing, saying the shower scene scarred her for life. It wasn’t just the main character’s sudden death, though. It was a primal fear borne of being caught completely naked and vulnerable.

Hitchcock, ever the master manipulator, kept the killer’s identity a secret through several high angle shots where you only see the top of his be-wigged head. Unlike the audience, Marion would have seen Norman Bates’ face as he killed her, but for viewers, the killer was unknown and would remain that way until the reveal in the cellar. Of course viewers would think it was the mysterious woman in the old Bates house, but when Sam finally grabs Norman and the wig falls off, the ruse is over. My mom said the reveal also shocked the audience.

While the death of Arbogast (Martin Balsam) later in the movie uses the same technique of sound to heighten fear, as Hitchcock only shows the knife coming in and out of the frame and not into the unlucky detective’s body, it’s the shower scene that persists in the popular imagination, and with good reason. Hitchcock’s use of the camera to deceive the audience into thinking it’s seen more than he’s shown has given that, and by extension, the entire film, an enduring power to terrify.

Unlike my mother, though, I still haven’t quite gotten over my fear of showers.

1 “Hitchcock” (Revised Edition) by François Truffaut, 1983, Simon & Schuster, Inc., p 277